Total Entries: 1045

Select one of the above filters

Year Filter:

Grape Sugar Exports from US Ports in 1890 - These maps show trends in the export flow of glucose from United States ports to the world from 1890 to 1910. Exporters shipped glucose (or “grape-sugar”) by the tens of millions of pounds throughout the later 1800s.

These maps show trends in the export flow of glucose from United States ports to the world from 1890 to 1910. Exporters shipped glucose (or “grape-sugar”) by the tens of millions of pounds throughout the later 1800s. The trade grew from three export ports in 1890 (Boston, New York, and Detroit) to six in 1910; it expanded from five global regional destinations to seven. In terms of quantity, the exports grew fifteen-fold from about 46 million to 728 million pounds in 1910. Some of the more notable trends are the increases in shipment to various South American countries by the early 1900s and shipments to new Asian markets beginning in 1905. The United Kingdom was such a large trading partner with the U.S. for glucose that their records offered more precision and, thus, the maps show direct flows to the UK while showing aggregated export streams to regions (Northern Europe, Southern Europe, South America) with less specificity in record keeping.

Because trade records provide a wide range of quantities per year, for the sake of reader legibility the maps represent proportions. For example, an arrow five-hatch-marks wide is five orders of magnitude greater than an arrow with one hatch mark, while the width of the five-hatch arrow is five times the width of the one-hatch arrow. Readers can thus view the maps to gain a sense of growth in export markets, relative quantities to various parts of the world, and sense of scale in the global marketplace for supposed adulterants.

The maps derive from government trade statistics that listed departure ports (export locations) and final destinations (import locations), but not together. For instance, while we know manufacturers shipped x pounds of glucose from New York in 1890, we do not know where, specifically, that specific quantity ended up. Therefore, the maps show the commodities shipped from individual U.S. ports to meet in the Atlantic before dispersing to final destinations.

In general, but not consistently, the government statistics used to construct theses maps documented foreign imports by country. Thus, in creating these maps the countries were aggregated into regions such as Northern Europe, Southern Europe, South America, Central America, Africa, and Asia. On the export side, various cities were aggregated into regions based on geographical proximity. The full data sets show specific nations.

For margarine, the trade grew from five export ports in 1890 (Boston, New York, Philadelphia, Detroit, and New Orleans) to six in 1910 and from five main global regional destinations to eight. This was an increase from about 6 million pounds to 26 million pounds by the first decade of the twentieth century.

These maps show the growth in exports of finished oleomargarine from the United States to other regions in the world from 1890 to 1910. The government distinguished these exports from raw oleo oil (see this page), which producers also shipped by the thousands of tons to foreign markets.

For margarine, the trade grew from five export ports in 1890 (Boston, New York, Philadelphia, Detroit, and New Orleans) to six in 1910 and from five main global regional destinations to eight. This was an increase from about 6 million pounds to 26 million pounds by the first decade of the twentieth century. Most of those foreign shipments first went to British colonial holdings in the West Indies, before being displaced in priority by shipments to Germany, Norway, and The Netherlands by the early twentieth century. As with shipments of raw oleo oil, notable trends include a change in destination into the early 1900s to include expanding markets in Asia, Central America, South America, and Africa.

Because trade records provide a wide range of quantities per year, for the sake of reader legibility the maps represent proportions. For example, an arrow five-hatch-marks wide is five orders of magnitude greater than an arrow with one hatch mark, while the width of the five-hatch arrow is five times the width of the one-hatch arrow. Readers can thus view the maps to gain a sense of growth in export markets, relative quantities to various parts of the world, and sense of scale in the global marketplace for supposed adulterants.

The maps derive from government trade statistics that listed departure ports (export locations) and final destinations (import locations), but not together. For instance, while we know manufacturers shipped x pounds of raw oleo oil from New York in 1890, we do not know where, specifically, that specific quantity ended up. Therefore, the maps show the commodities shipped from individual U.S. ports to meet in the Atlantic before dispersing to final destinations.

In general, government statistics used to construct theses maps documented foreign imports by country. Thus, in creating these maps the countries were aggregated into regions such as Northern Europe, Southern Europe, South America, Central America, Africa, and Asia. On the export side, various cities were aggregated into regions based on geographical proximity. The full data sets show specific nations.

Incredible book from 1891 explains how "It is found that with an exclusive meat diet composed of the ordinary average meat almost the exact quantities of both the CHNOS and CHO compounds can be obtained from bare subsistence up to that for forced work." and that other diets will require too much carbohydrates in order to get enough protein.

The three classes of proximate principles that are neces- sary to be understood in the intelligent study of the food- stuffs, and in the selection of the most efficacious diet in disease are best divided into three distinct divisions ; the inorganic, the CHO, and the CHNOS compounds, or a first, second, and third class.

First. The inorganic substances, such as water, the phosphates, chlorides, carbonates, sulphates, etc., etc. These chemical compounds all enter the body under their own form, either alone or in combination with the other two classes. They are not oxidized or split up within the system to enter into the chemical formation of other com- pounds, but are united mechanically with the proteid group, in fact, their whole action is, as it were, mechanical. After having served their purpose to the body they pass out of the system with the excretions absolutely unchanged in their composition. All medicinal compounds of a corresponding compo- sition and nature probably act in a similar mechanical manner.

Second. The CHO substances which have for their chemical composition the elements carbon, hydrogen, and oxygen only as fat, sugar, and starch. These substances are all oxidized or split up within the system, yielding heat, energy, lubrication, and rotundity only, and are finally eliminated from the body as carbon dioxide and water. The medicinal agents of like chemical construction probably are oxidized and broken up to yield their effects by a similar cycle of changes.

Third. The CHNOS substances or those which have for their chemical composition the elements carbon, hydrogen, nitrogen, oxygen, and sulphur. The common representatives of this group are called proteids, or the albuminous parts of milk, eggs, meats of all kinds, which chemically and histologically include fish, lobsters, crabs, turtles, oysters, clams, etc., also poultry and game. The nitrogenous or albuminous parts of all plant life, which is now commonly called vegetable proteid, is included in this class.

All these nitrogenous substances, irrespective of specific names, are somewhat slowly oxidized or split up within the system and are absolutely essential to form the different constituents of all the fluids, tissues, glands, and ferments of the body, being united mechanically in varying proportions with water and the mineral salts.

When these proteid bodies are normally transformed, their excrementitious products are urea, uric acid, kreatinine, carbon dioxide, and water in certain and definite proportions. If for any reason there is an abnormal transformation along this line of proteid metabolism, the relative quantity of urea falls and the uric acid rises. By closely studying these urinary changes and intelligently interpreting them, there is furnished an almost exact key to the perfection or imperfection of the oxidization processes and the nutritive condition of the body. By this method of study it is positively known whether the food-stuffs are absorbed and properly utilized by the system or not.

Another important phenomena to be remembered in connection with the oxidization of the proteid substances is the fact that a disturbance in their anabolism not only changes the relative proportions between the urea and the uric acid, but tends to develop an almost unlimited number of katabolins, some of which are perfectly inert, while others are as toxic and dangerous to life as the well-known cyanide compound prussic acid.

The action of the CHNO medicinal agents can he explained largely upon the same principles and chemical laws that govern the usefulness of the proteid bodies.

With an intelligent conception of these three classes of proximate principles and what results are obtained for the system by their perfect and what by their imperfect oxidization, a comparative table of the common substances rated as food-stuffs is instructive. This table subdivides each kind of food product into its three distinct classes of principles. The inorganic compounds, however, are subdivided into water and the inorganic salts, so that their true position may be more clearly elucidated and the whole subject made plainer.

[[Table 1]]

Having in this brief manner outlined the composition of the food-stuffs and intimated at the same time the absolute necessity of understanding thoroughly the chemical and physiological laws that control their usefulness within the system, it becomes possible to advance a step further and state the quantities necessary for the most perfect nutritive condition.

It also shows clearly how, by indulging too freely in any kind of food or by an unwise selection of the various kinds of proximate principles, the digestive system is constantly overtaxed, assimilation imperfectly effected and a host of diseased conditions developed. These abnormalties are brought about in the most insidious and often almost inappreciable manner, until, in some instances, well-defined symptoms are established by which a distinct name can be applied to the condition before attention is attracted to the malady. In a much larger percentage of the cases, however, the symptoms presented are so vague and changeable that the most learned specialist cannot possibly name the condition and sharply define the abnormalty so that it can be differentiated from many other states of a similar nature. Yet it is perfectly clear to every one, patient and practitioner, that something is decidedly wrong with the physiological mechanism of the system.

Briefly stated, it may be assumed that the following table, No. II., gives a pretty close and satisfactory basis how the first and second classes of proximate principles should be arranged as to the relative proportions needed of each, from bare subsistence up to the largest amount of mental and physical work.

[[Table 2]]

Before advancing any further in this physiological problem of food and nutrition, it must be admitted that the oxygenating capacity of the system is a limited one — but, fortunately for the human race, it has a moderately wide margin. There frequently comes a time, however, when this margin is exceeded, which is usually brought about by eating too large quantities of all kinds of food or too freely of the CHO classes of food-stuffs — as fat, sugar, and starches — or of both. As a natural sequence one of three things of necessity follows.

First. The respirations and circulation must be increased to supply more oxygen or the food-stuffs will be imperfectly oxidized. But Nature has set a limit upon the actions of the heart and lungs so that complete relief cannot be granted in this manner.

Second. The red blood corpuscles must be increased in number or empowered to carry more oxygen, or the absorbed food-stuffs will be imperfectly oxidized. But here again Nature has set a limit upon the number and carrying capacity of these anatomical bodies so that relief in this direction is wanting.

Third. The super-abundance of food-stuffs absorbed must be incompletely oxidized because the system has no means by which the extra amount of oxygen required can be furnished. This statement applies with special force to che proteid bodies on account of well-established chemical laws, which show that the CHO elements are quickly and completely transformed under all circumstances while the CHNOS are only perfectly transformed when everything is most favorable. The CHO compounds, as fat, sugar, and starch, are rapidly and easily oxidized, consequently they are the first elements to be changed, and they are also completely transformed into their final products ; this tends to leave a deficient quantity of oxygen to act upon and accomplish the more difficult task of carrying the nitrogenous com- pounds through their cycle of change and finally into perfect excrementitious substances. This defective supply of oxygen disturbs the perfect metabolism of the proteid bodies and produces an unlimited number of katabolins and furnishes a rational explanation for many, if not all, of the pathological conditions and symptoms that have to be treated. At least it is fair to assume that so long as the anabolic processes of the body are perfectly effected, no pathological lesion or abnormal symptom can be developed. Keeping constantly in mind the table indicating the relative proportions existing between the proteids and the CHO compounds, or the fats, sugars, and starches, and studying a little more closely the composition and comparative merits of the various food products, much valuable information is brought to light.

First. It is found almost impossible to arrange a mixed or vegetable diet so as to obtain the requisite amount of proteid elements without at the same time taking more than the needed quantity of the CHO compounds, that is, without introducing more than can be safely utilized or oxidized.

Second. It is found that with an exclusive meat diet composed of the ordinary average meat almost the exact quantities of both the CHNOS and CHO compounds can be obtained from bare subsistence up to that for forced work. Taking four ounces of pure proteid matter as the standard amount required in twenty-four hours to perfectly maintain the constructive forces of the system, the following tables are quite instructive, viz. :

[[Tables 3-7]]

Examples of this kind might be multiplied almost ad infinitum. With all of the tables, however, excepting Table No. VI., there is clearly shown a larger quantity of the CHO compounds than is found of proteid elements. This shows that with almost all kinds of food-stuffs and especially when taken in excessive quantities the system is liable to receive a superabundance of the CHO substances. The ease with which the requisite amounts of proteid matter can be rightly adjusted to meet the demands of the system is clearly demonstrated. These tables just as clearly illustrate that it is almost impossible to arrange any form of the mixed food-stuffs in such a manner that the system will not be constantly super- charged with the stimulating and non-nutritious compounds of CHO construction.

TABLE VIII.

This comprehensive comparative diet table, compiled and used by Prof. William H. Porter, of the New York Post-Graduate Medical School, has been worked out upon the atomic basis of the proximate principles, which enter into the construction of the ordinary food-stuffs.

It proves quite conclusively that Professor Porter's animal diet yields all that can be obtained by the use of a mixed diet containing the three elements — proteid, fat, and carbohydrate.

In fact, in the proportions as here given, it calls for the use of a little more oxygen than the mixed diet based upon the proportions given by Moleschott ; it also yields a little more carbon dioxide and water.

When it is remembered, however, that in the egg and the ordinary run of good meat, the proteid element is always a little more abundant than the fat, this excess of oxygen used — when taking an ordinary animal diet — will not be required, and the increased amount of carbon dioxide and water will not be produced, but the total results in excrementitious products cast off and the amount of heat and so-called energy evolved will come so very close to the amounts obtained by using Moleschott's mixed diet, that the two are practically the same.

The conclusion, therefore, is that the relative proportions of these two elements, proteid and fat, as commonly found in eggs, meat, and fish, come so nearly to the required physiological demands of the system that, in this class of food-stuffs, there is found an almost perfect standard for diet. By adding a very small allowance of bread and butter, it becomes absolutely perfect.

These chemical facts, based upon the atomicity of the Sood elements, explain the higher nutritive vitality developed in the carnivora as compared with the herbivora and vegetable feeding classes.

Again, in diseased conditions where the nutritive powers are severely overtaxed, the proteid and fat diet is especially serviceable, for by its use the expenditure of vital force in transforming the food-stuffs is kept at the lowest possible standard. Because, in the use of animal fat to the exclusion of the carbohydrates, the system is spared the necessity of laying out force and oxygen to convert the starch and various sugar elements into a diffusible glucose, and then into an alcoholic-like compound before they can be utilized by the animal economy for the production of heat and the so-called energy, which is finally computed in foot pounds of work accomplished.

This great saving in vital force by the exclusive use of fat — to supply the CHO elements necessary to produce the heat and energy required — is unquestionably the exact factor that enables the system to effect the cure in all the pathological conditions, which otherwise could not be carried on to a complete recovery.

These same laws make Kumysgen one of the most valuable food products ever produced, because it has been found, that only about one-half of the fat contained in milk is capable of being absorbed, and with the lactose converted into an alcoholic compound there is developed in Kumyss or Kumysgen, particularly in the latter, a partially predigested food-stuff which contains about equal quantities of proteid and fat in a state to be readily absorbed. This then corresponds exactly with the requirements found in Professor Porter's table, which consists of only proteid and fat.

Practical experience has long since taught that this form of dieting was the only kind available in connection with the successful treatment of the acute diseases.

This table is further a demonstration and confirma- tion from a chemical and physiological standpoint, of what has been so often repeated in a clinical way, that upon this purely proteid and fat diet, together with the administration of suitable medicinal agents, the most aggravated forms of digestive disturbances can be quickly removed, nutrition improved, and a healthy standard permanently re-established. They show conclusively that this form of animal diet yields the largest working power to the system for a given amount of food taken, and a similar amount of oxygen used to carry the food substances through their anabolic cycle of changes, and finally form and discharge from the body the resulting excrementitious products.

Reed and Carnrick explain why the exclusive meat diet is superior to a vegetarian diet when chemistry and anatomy are taken into account.

At this point, however, it may be well to mention that the standard amount of proteid matter taken, in the construction of all these tables, was 130 grammes — 4.5 ounces. Moleschott's original diet-table contained only 120 grammes or (4.2 ounces), but as almost all observers agree quite closely as to the amount of proteid material necessary to be used, and also as to the results obtained from its oxidization, the same quantity was used in all instances that a more exact comparison might be established. The chief difference of dispute, however, is in relation to the relative value of the fats and carbohydrates, and particularly in reference to the latter compounds.

In trying to develop out of a purely vegetable diet, anything like the same amount of working power for the system that is obtainable by the use of Porter's or Moleschott's diet, almost double the amount of proteid had to be taken with the proportionate rise in the fat and starch as is contained in the vegetable chosen.

To produce the same amount of work by using a vegetable diet necessitates the outlay of a much larger amount of oxygen, and the production and handling by the glandular structures of the body of an excessive amount of the nitrogenous excrementitious elements. These facts illustrate quite conclusively the manner in which the damage to the system is brought about by indulging too freely, or living exclusively upon a cereal or vegetable compound.

The vegetable proteid in these tables is further given an undue advantage, to which it is not justly entitled, by crediting it with the same atomic formula as that possessed by an animal proteid ; since the nitrogenous element found in plant-life contains a much larger number of nitrogen atoms, and consequently requires more vital force and oxygen to digest and assimilate it. This naturally decreases rather than improves the nutritive value of the proteid compound of vegetable origin.

An average of a compound fat molecule is taken as the working standard in all these tables.

Attention is also directed to a probable error in the rating of the heat-producing power of the carbohydrate. It is & commonly stated, that the comparative oxygenating capacity of a carbohydrate and fat is as one to two and one-half, but by their chemical atomicities, it is as one to thirteen, or thirteen and one-half in favor of the fat.

That such an error exists in the computations in Moleschott's standard is sustained by a comparative study of the atomicities of the food-stuffs used in both Porter's and Moleschott's diet tables, and of the amount of oxygen required for complete oxidization in both instances. In the former, or Porter's proteid and fat diet table, a little more oxygen is needed than is necessary in Moleschott's mixed diet* yet it is claimed that in the latter instance 393,170 kilogramme-metres or 54,358 more foot pounds of work is produced. This, however, is directly opposed by the smaller quantity of oxygen used in the oxidization processes. When this error in work, produced out of the carbohydrates in Moleschott's diet, is corrected in accordance with the difference in atomicity and the amount of oxygen used between the fat molecule and the carbohydrate molecule represented as glucose, and a computation is made in accord with the correction, a slight difference in work produced when living on a Moleschott's or Porter's diet, is found to exist. The increase in work produced, however, is now found to exist in connection with Porter's diet and is in accord with the larger amount of oxygen used, which makes atomicity, oxygen used, and work produced correspond, while the reverse was stated in the calculations formerly made in connection with Moleschott's diet.

If this error be true, as it appears to be, the profession have been sadly misguided in all their attempts in the construction of diet tables starting with Moleschott as their standard.

On the other side, if these chemical and physiological laws be true, as based upon the atomicity of the proximate principles, by carefully considering the percentage composition of each food product to be used, exact results can be obtained. Another point to which attention is called by Dr. Porter is this, that the factors 1.812 and 3.841, which are used in computing the kilogramme-metres in Table VIII., are taken from Frankland — Philosophical Magazine XXXII., and are those which are generally quoted in all scientific works upon physiological chemistry and upon diet.

In studying the proximate principles, however, by the atomicities, and considering the amount of oxygen required to completely transform a fat molecule into its final products of excretion water and carbon dioxide and a proteid molecule into its final products of excretion — urea, uric acid, kreatinine, carbon dioxide, water, etc. — it is found that only eighteen (18) more oxygen elements are used in the complete oxidization of the fat than in that of the proteid molecule. The computed amount of work performed by the oxidization of the fat molecule is found to be 530 foot pounds as compared to 250 foot pounds for the complete oxidization of the proteid molecule. This makes the eighteen (18) more elements of oxygen used in transforming the fat molecule result in the production of 280 more foot pounds of work than is obtained from the eighteen less used in the proteid.

From this a decided discrepancy is quite evident between the results obtainable by former calculations and those based upon our modern chemical atomicities.

However, for an illustrative and comparative study of the working power obtainable from the use of the various food-stuffs, this table is still of great value, as the same figures are used in each and all the calculations.

As these same factors, 1.812 and 3.841, appear in all the modern scientific works, they were retained in the arrangement of this table, but not without appreciating and calling attention to this discrepancy when the computation is based upon the atomicities of the food elements used, the amount of oxygen required, and the results obtained.

Again, it must be remembered that the proteids are not directly transformed into their final products, but undergo a series of intermediate changes, all of which require the use of oxygen and must of necessity yield more or less heat and energy, so that all our estimates are approximate.

When upon Moleschott's diet with the proteid substances raised to the common standard of 130 grammes and the carbohydrates rated in accord with the correction previously noted, it requires 36,115 oxygen elements to produce 678,270 kilogramme-metres or 93,773 foot pounds of work.

When upon Porter's diet of proteid and fat, it requires 38,415 oxygen elements to produce 734,890 kilogrammemetres or 101,602 foot pounds of work. When upon a purely vegetable diet that will yield anything like the requisite amount of work that can be obtained by using Moleschott's or Porter's diet, it requires 47,191 oxygen elements to produce 742,018 kilogramme-metres or 102,587 foot pounds of work.

To obtain the 63,748 more kilogramme-metres or 8,814 foot pounds of work out of the vegetable diet as compared with Moleschott's diet, it requires the expenditure of 11,076 more oxygen elements.

To obtain the 7,128 more kilogramme-metres or 985 foot pounds of work out of the vegetable diet as compared with Porter's diet, it requires the expenditure of 8,776 more oxygen elements. The vegetable diet in both instances yielding an excessive amount of nitrogenous excretory matter, carbon dioxide, and water.

A careful study of Table II. and VII., and Porter's diet in Table VIII., proves beyond a question of doubt that upon an exclusive diet of our ordinary average meat alone very nearly the required proportions of the proteids or CHNOS compounds and of the fat or CHO element can be established.

The only defect in the perfection of Table VII. and VIII. is found in the saline column, which contains much more mineral matter than perfect physiological laws indicate are required. This excess in saline or inorganic compounds, however, appears to be true in all kinds of food products — that is, if the proportion of salts in the milk is taken as the guide for a working basis. The reason for looking upon the amount of salts in the milk as the guide to the maximum quantity required is based upon the fact that during the infant period of life, where milk forms the only source of food supply, bone formation is most rapidly progressing, and the amount of mineral matter needed by the system is at its height and much larger than at any other period of life. The bones continue to grow and become fully and perfectly developed with the ordinary quantity of mineral matter contained in the milk.

Physiology also teaches that a little less than one ounce of mineral salts are required daily by the system, but in all the tables given, except the one containing milk alone, the amount of salts is fully up to or more than an ounce.

The only great objection that can be raised to an exclusive meat diet is the lack of variety, but that is quite easily adjusted by varying the kinds of meat used. The perfection of the proportionate composition of the proximate principles when using a meat diet, the smaller liability to imbibe an excessive quantity of any one kind and the little danger that there is of taking an excess of the CHO or stimulating and non-nutritious compounds, clearly establishes the fact that in meat we approach the nearest to an ideal food.

If attention is turned for a single moment to the lower orders of the animal kingdom, it is quite apparent that the most supple and intensely powerful organisms are found among the carnivora only. This tends to substantiate the high utility of the meat diet. Another interesting point is the almost universal absence of tuberculosis among meat-eating animals, while the vegetable-feeding class are specially prone to suffer from this fatal malady.

Reed and Carnrick explain how babies process milk and oxidize the fats, carbohydrates, and protein.

Again, the milk which is so generally considered as being fully equal to all the demands of the system, and especially so during the first few months of infant life, might be brought forward as proof positive and clearly illustrating the fact that nature calls for an excess of the CHO elements, because in the composition of the milk it is found that the CHO substances are about twice as abundant as the proteid or CHNOS elements. When these facts are examined a little more closely and scientifically, it is found that the pancreatic gland and its ferment-forming bodies are imperfecty developed at this period of life. Consequently, the fat, if emulsified and rendered capable of being absorbed by the lacteals of the villi, must have this transformation effected almost exclusively by the biliary fluid alone. It is further taught that the biliary secretion acts but little, if at all, upon vegetable fats and that it has the power to effectually emulsify only about one-half of the total quantity of animal fat introduced into the alimentary canal. This being true, fifty per cent, of the fat contained in the milk, together with the bile constantly flowing into the alimentary tract, is unquestionably utilized by the system as a natural laxative principle, and is undoubtedly the chief method by which nature effectually maintains the regular movements of the bowels and produces the daily evacuations so characteristic of a perfectly healthy infant.

The proportionately larger size of the liver in a child as compared with an adult also points to the fundamental importance of the hepatic gland and its secretion as a necessary agent of prime importance in the infant; the large size of the liver compared with other organs also indicates its great importance during adult life.

How much of the lactose — which is the form of sugar introduced in the milk — is inverted into glucose and rendered capable of being absorbed and utilized is an open question. In fact, there is no very reliable data upon this important point, but what is to be found upon the subject indicates quite positively that a considerable quantity of the lactose is not changed so as to be utilized by the system, but passes off with the faeces. Therefore, when the scientific truth is clearly appreciated, it is found that the relative proportion between the CHO and the CHNOS elements contained in the milk and that which can gain access to the vascular channels and be of service to the system is not far from equal in amount the major quantity, perhaps a little on the side of the CHO substances or in favor of the fat and sugar. Then, again, the infant requires a little more of the heat-producing compounds during the first few weeks or months than is needed a little later on or in adult life, because the proportionate amount of energy expended is greater in the infant and child than is the case during the adult period of life. Very early in the infant life there is comparatively little muscular action by which heat and energy can be evolved, while a large amount of heat is needed to maintain a perfect physiological condition, and for a time warmth must be artificially supplied. These conditions will admit of a little excess of the CHO elements during this period of life , but when the stage of infant muscular activity commences its never-ceasing motion, then the proportionate amount of the proteid substances must be raised and the CHO, or fat and sugar lowered, if the most perfect type of physiological development is to be effected.

Observing clinical phenomena a little more closely, it is quite apparent, as life advances, that milk is not equal to the demands of the system, and a more strongly proteid diet is urgently called for by nature. Eggs and lean meat must next be added to furnish this much-needed proteid pabulum for the constructive purposes of the animal economy, and out of which alone the most perfect muscles, glands, ferment bodies, and brain tissue can be formed.

By this process of reasoning, it is clearly and well established that even with the commonly supposed typical food-stuff, milk, it is not sufficiently perfect in its composition to thoroughly sustain the nutritive economy under all circumstances, but must have added to it a more liberal proteid pabulum. It is also clearly demonstrated that a portion of this excessive amount of fat is not taken up by the circulatory or lymphatic system but is used largely by nature as a laxative agent.

Proceeding a step further in the investigation of the clinical facts bearing upon this most interesting subject and there is found quite a common tendency among people at large to add to the nutritive supply of the infant not the most serviceable kind of food-stuffs in the way of an animal proteid of some kind, but on the contrary the more general practice is that of adding a cereal or vegetable compound, — one in which the CHO elements are very greatly in excess of the demands of nature. Another important point to be remembered in this connection is the well established fact that, although the proteid of vegetable origin, while in quite sufficient quantities, is a much higher nitrogenous compound and, as a rule, is far more difficult of digestion than a proteid body derived from the animal kingdom.

By this method of infant feeding in which an excess of the fat, sugar, and starch or CHO compounds are used, a natural taste and habit of eating food derived largely from ficially supplied. These conditions will admit of a little excess of the CHO elements during this period of life , but when the stage of infant muscular activity commences its never-ceasing motion, then the proportionate amount of the proteid substances must be raised and the CHO, or fat and sugar lowered, if the most perfect type of physiological development is to be effected. Observing clinical phenomena a little more closely, it is quite apparent, as life advances, that milk is not equal to the demands of the system, and a more strongly proteid diet is urgently called for by nature. Eggs and lean meat must next be added to furnish this much-needed proteid pabulum for the constructive purposes of the animal economy, and out of which alone the most perfect muscles, glands, ferment bodies, and brain tissue can be formed. By this process of reasoning, it is clearly and well established that even with the commonly supposed typical food-stuff, milk, it is not sufficiently perfect in its composition to thoroughly sustain the nutritive economy under all circumstances, but must have added to it a more liberal proteid pabulum. It is also clearly demonstrated that a portion of this excessive amount of fat is not taken up by the circulatory or lymphatic system but is used largely by nature as a laxative agent. Proceeding a step further in the investigation of the clinical facts bearing upon this most interesting subject and there is found quite a common tendency among people at large to add to the nutritive supply of the infant not the most serviceable kind of food-stuffs in the way of an animal proteid of some kind, but on the contrary the more general practice is that of adding a cereal or vegetable compound, — one in which the CHO elements are very greatly in excess of the demands of nature. Another important point to be remembered in this connection is the well established fact that, although the proteid of vegetable origin, while in quite sufficient quantities, is a much higher nitrogenous compound and, as a rule, is far more difficult of digestion than a proteid body derived from the animal kingdom. By this method of infant feeding in which an excess of the fat, sugar, and starch or CHO compounds are used, a natural taste and habit of eating food derived largely from the vegetable kingdom is engendered. The natural sequence is, that on through life the individual is apt to continue eating excessively of all kinds of food-stuffs and particularly those of the CHO and vegetable class. This poorly nourishes the body; adipose tissue in abundance is often acquired from the imperfectly transformed foodproducts. The appetite increases because the system is not properly sustained. The individual continues eating more and more until finally the marginal capacity of the system for supplying oxygen is reached and passed, digestion is imperfectly effected, and the oxidization powers of the body exceeded.

Reed and Carnrick explain dietary treatments for tuberculosis "Tuberculosis in the human subject is most frequently found in starch and sugar-fed subjects. The only line of treatment that has yielded any satisfactory results has been the sending of such cases to the wild mountain regions where the diet of necessity is largely of the animal class, such as game and fish. "

Observations among the animal kingdom show that the carnivora rarely have tuberculosis, while the vegetable feeders are particularly prone to this form of disease. Carnivora, while fed upon an animal diet, cannot be successfully innoculated with tubercular matter ; confined and fed upon an opposite class of food products and the experiments rapidly become successful.

Tuberculosis in the human subject is most frequently found in starch and sugar-fed subjects and in those who are compelled to live in close quarters.

The only line of treatment that has yielded any satisfactory results has been the sending of such cases to the wild mountain regions where the diet of necessity is largely of the animal class, such as game and fish. With this out- of-door life, an almost exclusive use of an animal diet, and a moderate amount of alcohol and cod-liver oil to supply what CHO element the system absolutely demands, has resulted in the positive cure of a fair percentage of genuine tubercular subjects.

Dr William Osler quotes Dr Sydenham's diabetes advice - which include "let the patient eat food of easy digestion, such as veal, mutton, and the like, and abstain from all sorts of fruit and garden stuff" as well as "carbohydrates in the food should be reduced to a minimum."

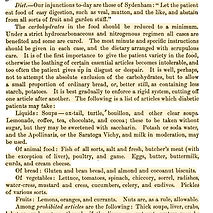

Diet. — Our injunctions to-day aro thoso of Sydenham : " Let the patient est food of easy digestion, eiich aa voal, mutton, and the like, and abstain from all sorts of fruit and garden stuff." The carbohydrates in tho food should be reduced to a minimum. Under a strict hydrocarbonaceous and nitrogenous regimen all casc«are benefited and some arc cured. The most minute and specific instructions should be given in each case, and the dietary arranged with scrupulous care^

It is of the first importance to give the patient variety in the food, otherwise the loathing of certain essential articles becomes intolerable, and too oft«u tho patient gives up in diegiiet or despair. It is wcl), perhaps, not to attempt the absolute exclusion of the carbohydrates, but to allow a small proportion of ordinary bread, or, belter still, as containing less starch, potatoes. It is beat gradually to cnforoe a rigid system, cutting oH one article after another. Tho following is a list of articles which diabetic patients may take :

Liquids; Soups — ox-tail, turtle, bouillon, and other clear soops

Lemonade, coffee, tea, chocolate, and cocoa; these to be taken without sugar, but they may bo sweetened with saccharin.

Potash or soda water, and the Apoltinatis, or the Saratoga Vichy, and milk in moderation, may be used.

Of animal food :

Fish of all sorts, salt and fresh,

butcher's meat (with the exception of liver),

poultry,

and game.

Eggs,

butter,

buttermilk,

curds,

and cream cheese.

Of bread : gluten and bran bread, and almond and coconut biscuits.

Of vegetables: Lettuce, tomatoes, spinach, chiccory, sorrel, radishes, water-cress, mustard and cress, cucumbers, celery, and endives. Pickles of various sorts.

5. Fruits : Lemons, oranges, and currants. Nuts are, as a rule, allowable

Among prohibited articles are the following :

Thick soups, liver, crabs, lobsters, and oysters; though, if the livers are cut out, oysters may be used.

Ordinary bread of all sorts (in quantity): rye, wheaten, brown, or white.

All farinaceous preparations, such as hominy, rice, tapioca, semolina, arrowroot, sago, and vermicelli.

Of vegetables : Potatoes, turnips, parsnips, sqimslies, vegetable marrow of all hinds, beets, corn, artichokes, and asparagus.

Of liquids: Beer, sparkling wine of all sorts, and the sweet aerated drinks.

The chief difficulty in arranging the daily menu of a diabetic patient is the bread, and for it various substitutes have been advised — ^bran bread, gluten bread, and almond biscuits. Most of these are unpalatable, and the patients weary of them rapidly. Too many of them are gross frauds, and contain a very much greater proportion of starch than represented. A friend, a distinguished physician, who has, unfortunately, had to make trial of a great many of them, writes : 'That made from almond flour is usually so heavy and indigestible that it can only be used to a limited extent. Gluten flour obtained in Paris or London contains about 15 per cent of the ordinary amount of starch and can be well used. The gluten flour obtained in this country has from 35 to 45 per cent of starch, and can be used successfully in mild but not in severe forms of diabetes." ' Unless a satisfactory and palatable gluten bread can be obtained, it is better to allow the patient a few ounces of ordinary bread daily. The " Soya " bread is not any better than that made from the best gluten flour. As a substitute for sugar, saccharin is very useful, and is perfectly harm- less. Glycerin may also be used for this purpose. It is well to begin the treatment by cutting off article after article until the sugar disappears from the urine. Within a month or two the patient may gradually be allowed a more liberal regimen. An exclusively milk diet, either skimmed milk, buttermilk, or koumyss, has been recommended by Donkin and others. Certain cases seem to improve on it, but it is not, on the whole, to be recommended.

Osler describes oxaluria which occurs in the urine and the crystals form a calculus. "The amount varies extremely with the diet, and it is increased largely when such fruits and vegetables as tomatoes and rhubarb are taken"

VII. Oxaluria.

Oxalic acid occurs in the urine, in combination with lime, forming an oxalate which is held in solution by the acid phosphate of soda. About .01 to .03 gramme is excreted in the day. It never forms a heavy deposit, but the crystals— usually octahedra, rarely dumb-bell-shaped— collect in the mucus-cloud and on the sides of the vessel. The amount varies extremely with the diet, and it is increased largely when such fruits and vegetables as tomatoes and rhubarb are taken. It is also a product of incomplete oxidation of the organic substances in the body, and in conditions of increased metabolism the amount in the urine becomes larger. It is stated also to result from the acid fermentation of the mucus in the urinary passages and the crystals are usually abundant in spermatorrhoea. When in excess and present for any considerable time, the condition is known as oxaluria, the chief interest of which is in the fact that the crystals may be deposited before the urine is voided, and form a calculus. It is held by many that there is a special diathesis associated with this state and manifested clinically by dyspepsia, particularly the nervous form, irritability, depression of spirits, lassitude, and sometimes marked hypochondriasis. There may be in addition neuralgic pains and the general symptoms of neurasthenia. The local and general symptoms are probably dependent upon some disturbance of metabolism of which the oxaluria is one of the manifestations. It is a feature also in many gouty persons, and in the condition called lithaemia.

Dr Osler explains the disease of gout and its etiology (hereditary, food, alcohol, lead) and theories (uric-acid, nervous, Ebstein's), however, the treatment of the chronic condition is a low carb diet where "starchy and saccharine articles of food are to be taken in very limited quantities."

VI. GOUT (Podagra)

Definition. A nutritional disorder, associated with an excessive formation of uric acid, and characterized clinically by attacks of acute brltis, by the gradual deposition of urate of soda in and about the joints, and by the occurrence of irregular constitutional symptoms.

Etiology. — It is now generally recognized that the disease depends upon disturbed metabolism ; most probably upon defective oxidation of nitrogenous food-stuffs.

Among important etiological factors in gout are the following:

(a) Hereditary Influences — Statistics show that in from fifty to sixty per cent of all cases the disease existed in the parents or grandparents. The transmission is supposed to be more marked from the male side. Cases with a strong hereditary taint have been known to develop before puberty. The disease has been seen even in infants at the breast. Males are more subject to the disease than females. It rarely develops before the thirtieth year; and in large majority of the cases the first manifestions appear before the age of fifty,

(b) Alcohol is the most potent factor in the etiology of the disease. Fermented liquors favor its development much more than distilled spirits, and it prevails most extensively in countries like England and Gennany, which consume the most beer and ale. Probably the greater tendency of malt liquors to induce gout is associated with the production of an acid dyspepsia. The lighter beers used in this country are much less liable to produce gout than the heavier English and Scotch ales,

(c) Food plays a role equal in importance to that of alcohol. From the time of Hippocrates overeating has been regarded as a special predisposing cause. The excessive use of food, particularly of meats, disturbs gastric digestion and leads to the formation of lactic and volatile fatty acids. It is held by Garrod and others that these tend to decrease the alkalinity of the blood and to reduce its power of holding urates in solution. A special form of gouty dyspepsia has been described. A robust and active digestion is, however, often met in gouty persons. Gout is by no means confined to the rich. In England the combination of poor food, defective hygiene, and an excessive consumption of malt liquor makes the "poor man's gout" a common affection.

(d) Lead. Garrod has shown that workers In lead are specially prone to gout. In thirty per cent of his hospital cases the patients had been painters or workers in lead. The association is probably to be sought in the production by the poison of arteriosclerosis and chronic nephritis. Something in addition is necessary, or certainly in this country we should more frequently see cases of this kind so common in London hospitals. Chronic lead-poisoning here frequently associated with arteriosclerosis and contracted kidneys, but acute arthritis is rare. Gouty deposits are, however, to be found, in the big-toe joint and in the kidneys in those cases.

There are three theories with reference to gout :

(1) The Uric-acid Theory. — Sir Alfred Garrod, to whom the profession is indebted for so many careful studies in this disease, showed that there was an increase in the uric acid in the blood, due either to increased production or to diminished elimination ; and that the alkalinity of the blood was also lessened. He attributes the deposition of the urate of soda the diminished alkalinity of the plasma, which is unable to hold it in solution. An increase in the quantity of the uric acid produced, or any interference with elimination through the kidneys, may cause a sudden outbreak. The acute paroxysm is due to an accumulation of the urates the blood, which he believes are responsible also for the preliminary dyspepaia, the coated tongue, the irritability of temper, and the general feelings of malaise. The sudden deposit of the cryst;itline urates about thf joint leads to inflammation. {H) The

Nervous Theory. — The view of Cullen that gout was primarily an affection of the nervous system has been modified into a neuro-humoral view which has been advocated particularly by Sir Dyce Duckworth. On this theory there is a basic, arthritic stock-a diathetic habit, of which gout and rheumatism are two distinct branches. The gouty diathesis is expressed in a neurosis of the nerve-centres, which may be inherited acquired; and (b) "a peculiar incapacity for normal elaboration within the whole body, not merely in the liver or in one or two organs, of food, whereby uric acid is formed at times in excess, or is incapable of being duly transformed iuto more soluble and less noxious product. (Duckworth). The explosive neuroses and the influence of depressing circumstances, physical or mental, point strongly to the part played by the nervous system in the disease.

(3) Ebstein's Theory. — A nutritive tissue disturbance is the priflii change leading to necrosis, and in the necrotic areas the urates are posited. This is not unlike the view of Ord, who holds that there a tendency, inherited or acquired, to a special form of tissue degent tion.

Morbid Anatomy. — The hold shows an excces of uric acid, as proved originally by Garrod. The uric acid may be obtained from the blood-serum by the method known as uric-acid thread experiment, or from the serum obtained from a blister....The primary change, according to Ebstein, is a local necrosis, due to the presence of an excess of urates in the blood. This is seen in the cartilage and other articular tissues tissues in which the nutritional currents are slow.

Symptoms.--Gout is usually divided into acute, chronic, and irregular forms.

Treatment-- Individuals who have inherited a tendency to gout, or who have shown any manifestions of it, should live temperately, abstain from alcohol, and eat moderately. An open-air life, with plenty of exercise and regular hours, does much to counteract an inborn tendency to the disease.

Diet--Experience has shown that a modified nitrogenous diet is the most suitable. Starchy and saccharine articles of food are to be taken in very limited quantities; as "the conversion of anatized food is more complete with a minimum of carbohydrates than it is with an excess of them-in other words, one of the best means of avoiding the accumulation of lithic acid in the blood is to diminish the carbohdyrates rather than the anotized foods" (Draper).

Meats of all kinds, except perhaps the coarser sorts, such as pork and veal, and salted provisions, may be used. Eggs, oysters, and f ish may be taken. Lobsters and crabs, particulary when made into salaids, are to be eschewed. The sugar should be reduced to a minimum. The sweeter fruits should not be taken. L Oranges and lemons may be allowed. Strawberries, bananas, and melons should not be eaten. If necessary, saccharin may be substituted. for cane sugar. Potatoes should be sparingly used. The fresh vegetables, such as lettuce, cucumbers, tomatoes, and cauliflower, may be taken freely. Hot rolls and cakes of all sorts, hominy, grits, and the more starchy forms of prepared foods are not suitable. The various articles of diet prepared from corn should be avoided. Fats are easily digested and may be taken freely. In obstinate cases great benefit is derived with an exclusively milk diet.

Persons with a gouty tendency should be encourage to drink freely of such mineral waters as they prefer. They kep the interstitial circulation active and so favor elimination. Milk and potash-water form a pleasant and wholesome drink for a lithamic patient. Alcohol in all forms should be avoided. When from any cause a stimulant is indicated, claret, dry sherry, or good whisky is preferable. Champagne is particularly pernicious. Persons with a marked tendency to lithaemia should be urged to restrict the appetite and to take only a moderate amount of food. Overeating is not far behind excessive drinking in its injurious effects. Indeed, a majority of people over forty years of age take more food than is required to maintain the equilibrium of health. Gout, in many cases, is evidence of an overfed, overworked, and consequently clogged machine.

In the chronic and irregular forms of gout the treatment by hygiene and diet is most suitable.

Osler explains what happens when one gets scurvy but repeats the myth that vegetables are necessary to cure it. He even quotes the theory of Ralfe who predated him 10 years but did not mention that meat can cure or prevent scurvy.

X. SCURVY {Scorbutus). Deflnition. —

A constitutional disease characterized by great debility with anemia, a spongy condition of the gums, and a tendency to haemorrhages.

Etiology — The disease has been known from the earliest times, and has prevailed particularly in armies in the field and among sailors on long voyages.

From the early part of this century, owing largely to the efforts of Lind and to a knowledge of the conditions upon which the disease depends, scurvy has gradually disappeared from the naval service. In the mercantile marine, cases still occasionally occur, owing to neglect of proper and suitable food.

The disease develops whenever individuals have subsisted for prolonged periods on a diet in which fresh vegetables or their substitutes are lacking.

In comparison with former times it is now a rare disease. In seaport towns sailors suffering with the disease are occasionally admitted to hospitals. In large almshouses, during the winter, cases are occasionally seen.* On several occasions in Philadelphia characteristic examples were admitted to my wards from the almshouse. Some years ago it was not very uncommon among the lumbermen in (be winter camps in the Ottawa Valley. Among the Hungarian, Bohemian, and Italian miners in Penn- sylvania, cases of the disease are not infrequent. This so-called land scurvy differs in no particular from the disease in sailors. An insufficient diet appears to be an essential element in the disease, and all observers are now unanimous that it is the absence of those ingredients in the food which are supplied by fresh vegetables. What these constituents are has not yet been definitely determined. Garrod holds that the defect is in the absence of the potassic salts. Others believe that the essential factor is the absence of the organic salts prevent in fruits and vegetables. Ralfe, who has made a very careful study of the subject, believes that the absence from the food of the malates, citrates, and lactates reduces the alkalinity of the blood, which depends upon the carbonates directly derived from these salts. This diminished alkalinity, gradually produced in the scurvy patients, is, he believes, identical with the effect which can be artificially produced in animals by feeding them with an excess of acid salts; the nutrition is impaired, there are ecchymoses, and profound alterations in the characters of the blood. The acidity of the urine is greatly reduced and the alkaline phosphates are diminished in amount.

In opposition to this chemical view it has been urged that the disease really depends upon a specific micro-organism.

Other factors play an important port in the disease. particularly physical and moral influences: overcrowding, dwelling in cold, damp qnartera, and prolonged fatigue under deprusing inflnernees, as daring tbe retreat of an army. Among prisoners, mental depression plays an important part. It is stated that epidemics of the disease have broken out in the French convict-ships en route to New Caledonia, even when the diet was amply sufficient. Nostalgia is sometimes an important element. It is an interesting fact that prolonged starvation in itself does not cause scurvy. Not one of the professional fasters of late years has displayed any scorbutic symptom.

The disease attacks all ages, but, but the old are more susceptible to it. Sex has no special influence, but during the siege of Paris it was noted that the males attacked were greatly in excess of the females. Infantile scurvy will be considered in a special note.

Morbid Anatomy.-- The anatomical changes are marked, though by no means specific, and are chiefly those associated with haemorrhage. The blood is dark and fluid. There are no characteristic microscopic alterations. The bacteriological examination has not yielded anything very positive. Practically there are no changes in the blood, either anatomical or chemical, which can be regarded as peculiar to the disease. The skin shows the ecchymoses evident during life. There are haemorrhages into the muscles, and occasionally about or even into the joints. Haemorrhages occur in the internal organs, particularly on the serous membranes and in the kidneys and bladder. The gums are swollen and sometimes ulcerated, so that in advanced cases the teeth are loose, and have even fallen out. Ulcers are occasionally met with in the ileum and colon, haemorrhages are extremely common into the mucous membranes. The spleen is enlarged and soft. Parenchymatous changes are constant in the liver, kidneys, and heart.

Symptoms. — The disease is insidious in its onset. Early symptoms are loss in weight, progressively developing weakness, and pallor. Very soon the gums are noticed to be swollen and spongy, to bleed easily, and in extreme cases to present a furifeous appearance. The teeth may become loose and even fall out. Actual necrosis of the jaw is not common. The breath is excessively foul. The tongue is swollen, but may be red and not much furred. The salivary glands are occasionally enlarged. The lesions of the gums are rarely absent. The skin becomes dry and rough, and ecchymoses soon appear, first on the legs and then on the arms and trunk. They are petechial, but may become larger, and when subcutaneous may cause distinct swellings. In severe cases, particularly in the legs, there may be effusion between the periosteum and the bone, forming irregular nodes, which, in the case of a sailor from a whaling vessel, who came under my observation, had broken down and formed foul-looking sores. The slightest bruise or injury causes haemorrhage into the injured part. Edema about the ankles is common. Haemorrhage from the mucous membranes are less constant symptoms. Epistaxis is, however, frequent. Haemoptysis and haematemesis are uncommon. Hasmaturia and bleeding from the bowels may be present in very severe cases.

Palpitation of the heart and feebleness and irregularity of the impulse are prominent symptoms. A haemic murmur can usually be heard at the base, haemorrhagic infarction of the lungs and spleen has been described. Respiratory symptoms are not common. The appetite is impaired, and owing to the soreness of the gums the patient is unable to chew the food. Constipation is more frequent than diarrhea. The urine is often albuminous. The changes in the composition of the urine not constant; the specific gravity is high; the color is deeper; and the phosphates are increased. The statements with reference to the inorganic constituents are contradictory. Some say the phosphates and potash are deficient; others that they are increased. There are mental depression, indifference, in some cases headache, and in the latter stages delirium. Cases of convulsions, of hemiplagia, and of meningeal haemmorhage have been described. Remarkable ocular symptoms are occasionally met with, such as night-blindness or day-blindness.

Prognosis: -- The outlook is good, unless the disease is far advanced and the conditions persist which lead to its development. During the Civil War the death-rate was sixteen per cent.

Prophylaxis.--The Regulations of the Board of Trade require that a sufficient supply of antiscorbutic articles of diet is taken on each ship; so that now, except as the result of accident, the occurenc of scurvy on board a vessel should lead to the indictment of the captain or owners for criminal negligence, an outbreak of the disease in an almshouse is evidence of culpable neglect on the part of the managers.

Treatment--The juice of two or three lemons daily and a varied diet, with plenty of fresh vegetables, suffice to cure all cases of scurvy, unless far advanced. When the stomach is much disordered, small quantities of scraped meat and milk should be given at short intervals, and the lemon-juice in gradually increasing quantities. As the patient gains in strength,the diet may be more liberal and he may eat freely of potatoes, cabbage, water-cresses, and lettuce

Gary Taubes wrote in his new book The Case For Keto a paragraph that I want to dedicate this database towards:

"I did this obsessive research because I wanted to know what was reliable knowledge about the nature of a healthy diet. Borrowing from the philosopher of science Robert Merton, I wanted to know if what we thought we knew was really so. I applied a historical perspective to this controversy because I believe that understanding that context is essential for evaluating and understanding the competing arguments and beliefs. Doesn’t the concept of “knowing what you’re talking about” literally require, after all, that you know the history of what you believe, of your assumptions, and of the competing belief systems and so the evidence on which they’re based?

This is how the Nobel laureate chemist Hans Krebs phrased this thought in a biography he wrote of his mentor, also a Nobel laureate, Otto Warburg: “True, students sometimes comment that because of the enormous amount of current knowledge they have to absorb, they have no time to read about the history of their field. But a knowledge of the historical development of a subject is often essential for a full understanding of its present-day situation.” (Krebs and Schmid 1981.)