Title:

Turtle and Tortoise hunting and processing provided easy calories and cognitive percussion enhancements

Abstract:

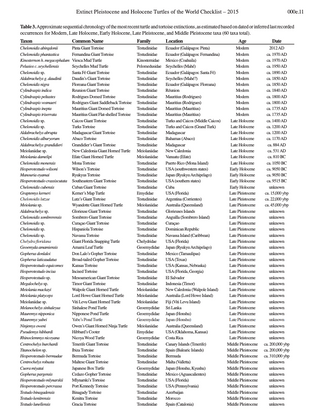

Abstract. – We provide a first checklist and review of all recognized taxa of the world’s extinct

Pleistocene and Holocene (Quaternary) turtles and tortoises that existed during the early rise

and global expansion of humanity, and most likely went extinct through a combination of earlier

hominin (e.g., Homo erectus, H. neanderthalensis) and later human (H. sapiens) exploitation, as

well as being affected by concurrent global or regional climatic and habitat changes. This checklist complements the broader listing of all modern and extant turtles and tortoises by the Turtle

Taxonomy Working Group (2014). We provide a comprehensive listing of taxonomy, names,

synonymies, and stratigraphic distribution of all chelonian taxa that have gone extinct from approximately the boundary between the Late Pliocene and Early Pleistocene, ca. 2.6 million years

ago, up through 1500 AD, at the beginning of modern times. We also provide details on modern

turtle and tortoise taxa that have gone extinct since 1500 AD. This checklist currently includes

100 fossil turtle and tortoise taxa, including 84 named and apparently distinct species, and 16 additional taxa that appear to represent additional valid species, but are only identified to genus or

family. Modern extinct turtles and tortoises include 8 species, 3 subspecies, and 1 unnamed taxon,

for 12 taxa. Of the extinct fossil taxa, terrestrial tortoises of the family Testudinidae (including

many large-bodied island forms) are the most numerous, with 60 taxa. When the numbers for

fossil tortoises are combined with the 61 modern (living and extinct) species of tortoises, of the 121

tortoise species that have existed at some point since the beginning of the Pleistocene, 69 (57.0%)

have gone extinct. This likely reflects the high vulnerability of these large and slow terrestrial (often

insular) species primarily to human exploitation. The other large-bodied terrestrial turtles, the giant horned turtles of the family Meiolaniidae, with 7 taxa (also often insular), all went extinct

by the Late Holocene while also exploited by humans. The total global diversity of turtles and

tortoises that has existed during the history of hominin utilization of chelonians, and that are

currently recognized as distinct and included on our two checklists, consists of 336 modern species and 100 extinct Pleistocene and Holocene taxa, for a total of 436 chelonian species. Of these,

109 species (25.0%) and 112 total taxa are estimated to have gone extinct since the beginning of

the Pleistocene. The chelonian diversity and its patterns of extinctions during the Quaternary

inform our understanding of the impacts of the history of human exploitation of turtles and the

effects of climate change, and their relevance to current and future patterns.

Key Words. – Reptilia, Testudines, turtle, tortoise, chelonian, taxonomy, distribution, extinction,

fossils, paleontology, archaeology, humanity, hominin, exploitation, chelonophagy, megafauna,

island refugia, climate change, Pliocene, Pleistocene, Holocene, Anthropocene, Quaternary

Details

There is an abundance of literature on the prehistoric Pleistocene and Holocene use and consumption of turtles and tortoises by earlier hominins and later humans, with many documented finds of turtle bones from archaeological sites and kitchen middens and inhabited caves (see below). It is beyond the scope of this checklist at present to document all of these records, although such a compilation would be extremely valuable. However, we make some noteworthy observations from this literature. One of the more striking results of our survey of Pleistocene and Holocene turtle and tortoise extinctions is that fossil taxa of terrestrial species, notably the Testudinidae and Meiolaniidae, are disproportionately represented, a factor that we link to the consumption of turtles (chelonophagy) by earlier hominins and later humans. As is true today in most tropical human subsistence hunter-gatherer societies, it was also likely true during the earlier days of humanity: any tortoise encountered was a tortoise collected and consumed. These slowmoving and non-threatening shelled terrestrial animals required minimal effort to find and, even when giant and heavy, were easily collected by bands of huntergatherers and could be stored alive for long periods of time to be eaten in times of need. Tortoises were, essentially, the earliest pre-industrial version of “canned food”, and early hominins began to collect and eat them as they developed the transformational ability to open their shells and butcher them using primitive stone tools (Oldowan Paleolithic technology), the earliest version of “can-openers”. Turtles and tortoises were an excellent dietary source of protein and were an important component of the subsistence diet of many early hominins (Steele 2010; Thompson and Henshilwood 2014). Bigger tortoises and larger-bodied species were more visible in the landscape and were probably preferentially collected, yielding more food for consumption, and probably gradually extirpated more rapidly as a result, leaving smaller tortoise species and the more elusive freshwater turtles to survive longer.

Our working hypothesis is that many of the giant tortoises of the family Testudinidae and the giant horned turtles of the family Meiolaniidae that went extinct during these times were primarily extirpated by hominin and human overexploitation during the relatively long rise and global spread of humanity from the end of the Pliocene through the Pleistocene and Holocene and into the present. However, many of these giant species were also no doubt affected to varying degrees by the relatively sudden global cooling that began towards the end of the Pliocene at about 3.2 million ybp, leading to the Northern Hemisphere Glaciation and beginning of the Pleistocene (Zachos et al. 2001). Additionaly, we hypothesize that most smaller tortoises and freshwater turtles that went extinct during these times were probably not necessarily primarily extirpated by humanity, but possibly more likely as a result of climate and habitat change, though probably also while being exploited to a lesser degree. In addition, many of the early Plio-Pleistocene “extinctions” may instead represent evolutionary phylogenetic transitions from earlier to subsequent chronospecies or paleospecies, with many of these possibly primarily affected by global cooling and glaciation (Zachos et al. 2001).

These patterns of early human exploitation have been corroborated by the studies of Stiner et al. (1999, 2000) on the subsistence use of large vs. small game, including Greek Tortoises (Testudo graeca), from the Paleolithic of Israel. Their studies demonstrated a significant chronologic decrease in the size of tortoises utilized, with those collected from 150,000 to 100,000 ybp being very much larger than those collected between 100,000 to 11,000 ybp, reflecting the effect of constant human exploitation pressures on tortoise sizes over long periods of time. Further extensive analyses of the same and additional material by Speth and Tchernov (2003) confirmed that human exploitation was directly correlated with decrease in tortoise size, particularly during a sudden human population growth pulse at around 44,000 ybp. Smaller and faster freshwater turtles, which probably required greater effort to collect, were apparently not exploited as frequently by early hominin hunter-gatherer societies, as the slower terrestrial tortoises were (Stiner et al. 2000; O’Reilly et al. 2006; Blasco et al. 2011).

Human exploitation of marine turtles also started long ago, with the earliest archaeological records of marine turtle bones from middens in the Arabian Peninsula and the Persian Gulf dating back to approximately 7000 ybp, or ca. 5000 BC (Beech 2000, 2002). Indeed, the earliest historical written documentation of people eating turtles was by the Greek historian and geographer Agatharchides of Cnidus, who lived in ca. 250 BC. He described a tribe of primitive people that he called the “Chelonophagi” (Χελωνοφάγοι) (= “Turtle-eaters”), who lived on islands in the southern Red Sea area between Africa and Arabia and ate giant sea turtles, using their shells for building shelters and as boats (Burstein 1989). We do not attempt to summarize the extensive literature on the history of human exploitation of marine turtles, well done already by Frazier (2003). We note, however, that despite the fact that most extant marine turtle species are currently assessed on the IUCN Red List as being Threatened (Vulnerable, Endangered, and Critically Endangered), there are no data to suggest that hominins or humans have yet contributed to the extinction of any marine turtle species. This would also have been unlikely, given 1) the generally global or at least widespread regional ranges of most sea turtle species, 2) their propensity to nest on offshore islands (like many seabirds), and 3) their developmental and/or foraging habitats often including the open ocean, making them relatively inaccessible to exploitation by humans. Hopefully, these factors and a continued conservation ethic will help prevent any anthropogenic extinctions of sea turtles. Hominin Chelonophagy Our review indicates that hominin consumption of turtles and tortoises has occurred since the earliest development of Oldowan stone technology in eastern and southern Africa and that it has gradually spread out of Africa in conjunction with the evolution of the genus Homo and the gradual migratory global spread of humanity. Turtles and tortoises have comprised an important component of the subsistence diet of evolving humanity. Africa. — The broad pattern of extinction outlined above is born out by the turtle fossil record from Olduvai Gorge in Tanzania, at the very heart of modern human origins. Studies by Auffenberg (1981), based on archaeological excavations by the Leakeys, demonstrated that the Early Pleistocene Australopithecus, and other early hominins, Homo habilis and probably H. erectus, gathered large numbers of chelonians. At these and slightly older Late Pliocene levels at some of these sites, there were a few remains of an extinct giant tortoise (“Aldabrachelys” laetoliensis), an extinct smaller tortoise (Stigmochelys brachygularis), and an extinct terrestrial pelomedusid (Latisternon microsulcae) mixed in with many still-extant freshwater turtles (Pelusios sinuatus) and a few still-extant medium-sized tortoises (Stigmochelys pardalis). Later, in the Middle Pleistocene, there were mainly large numbers of P. sinuatus and only an occasional S. pardalis. This pattern of utilization is consistent with early overexploitation and extirpation of the terrestrial tortoises leading to later availability of mainly freshwater turtles. This pattern is repeated throughout the continent. Several finds of Plio-Pleistocene giant tortoises have been recovered from continental Africa, often assigned to Centrochelys or Stigmochelys (Harrison 2011), including from Hadar, Ethiopia (3.4–3.2 million ybp), Omo, Ethiopia (3.5–2.5 million ybp), Bahr el Ghazal, Chad (3.5–3.0 million ybp), Kaiso Beds, Uganda (2.3–2.0 million ybp), and Olduvai, Tanzania (4.4– 2.6 million ybp). Giant tortoises somewhat similar to extant Stigmochelys pardalis, but more likely an undescribed species, have also been found at Rawi, the Early Pleistocene Oldowan site (ca. 2.5 million ybp) on the Homa Peninsula in Kenya (Broin 1979; F. Lapparent de Broin, pers. comm.). The extinction of these and several other giant forms in Africa occurred almost simultaneously at around 2.6–2.5 million ybp, coinciding with the evolution of Homo in Africa and the early Oldowan use of stone tools for butchering (Harrison 2011). While there are numerous records of Late Pliocene to Early Pleistocene fossil giant tortoises from continental Africa, none except for the somewhat smaller extant Centrochelys sulcata and Stigmochelys pardalis have been reported from more recent deposits (Lapparent de Broin 2000; Wood 2003). Though many earlier Pleistocene records of turtles associated with hominin archaeological sites have not yet shown specific taphonomic indicators of butchering, there is no doubt that turtles and tortoises have been exploited for a long time. Indeed, in addition to the circumstantial evidence from Olduvai Gorge and other parts of Africa, evidence from the Plio-Pleistocene of the Chiwondo Beds in Malawi (3,750,000 to 2,000,000 ybp) indicate that early hominins, such as Paranthropus boisei and Homo rudolfensis, crushed freshwater turtle shells (Karl 2012). Additionally, a tortoise shell from the Early Pleistocene Sterkfontein Australopithecus site in South Africa (2,000,000 to 1,600,000 ybp) appears as if it may have been butchered (Broadley 1997). At Lake Turkana in Kenya, Early Pleistocene hominins at about 1,950,000 ybp (pre-dating Homo erectus) butchered and consumed many turtles, in addition to small and large mammals (notably hippopotamus), crocodiles, and fish (notably air-breathing catfish) (Braun et al. 2010). Stone tool marks recorded from the insides of turtle carapacial fragments found there have indicated that they were actively butchered (Braun et al. 2010; Archer et al. 2014). Similarly, Thompson and Henshilwood (2014) documented butchering and the high nutritional value and high levels of exploitation of still-extant Angulate Tortoises (Chersina angulata) in the Middle Stone Age of South Africa at ca. 100,000 to 70,000 ybp. Also in the Middle and Late Stone Age of South Africa (ca. 70,000–2000 ybp), Klein and Cruz-Uribe (1983, 2000) and Steele and Klein (2006) documented the gradual decrease in size of C. angulata harvested and consumed by humans in the region. Though habitat and climate deterioration could have played a role in the decreasing size of the tortoises, these authors concluded that hunting pressure was significantly greater in the Late Stone Age when the human population density had grown significantly and the increased exploitation affected the size of tortoises available for harvesting. Avery et al. (2004) noted accumulations of burned tortoise shells in Paleolithic Early Holocene South African huntergatherer sites from 10,700 to 9600 ybp and later, that were suggestive of focused collection and consumption of tortoises burned in bush fires. We also note the description by Broadley (2007) of what he suggested was an “anomalous” specimen of Kinixys, most similar to extant K. spekii, from an Early Holocene (ca. 9400 ybp) cave site in Zimbabwe. We have not listed this testudinid as an unnamed extinct taxon, but based on the morphological characteristics of the limited fragmentary material, it might be. Middle East and

Europe. — The Early Pleistocene Dmanisi site in Georgia in the Caucasus, dated at ca. 1,800,000 ybp, represents the earliest known occurrence of Homo outside of Africa. This site includes many tortoise bones identified as the Greek Tortoise, Testudo graeca, in association with the primitive hominin (probably H. erectus) that occurred there (Blain et al. 2014). In Eurasia, remains of the widespread species of the genera Testudo, Emys, Mauremys and further south, also of Rafetus and Trionyx, are common in archaeological sites of Homo sapiens and H. neanderthalensis. Documented evidence of active butchering and exploitation of turtles and tortoises has been shown from the Early Pleistocene of Spain, approximately 1,200,000 ybp (Blasco et al. 2011), where a taphonomic analysis of turtle bones demonstrated that cave-dwellers (Homo sp.) used stone tools to prepare and consume many medium-sized Hermann’s Tortoises, Testudo hermanni, and occasionally the smaller European Pond Turtle, Emys orbicularis. Stiner et al. (1999, 2000) also demonstrated the significance of freshwater turtles (E. orbicularis) and tortoises (Testudo spp.) in Paleolithic subsistence economies for up to 120,000 ybp in Italy and 200,000 ybp in Israel, respectively. Also in Spain, in the Middle Pleistocene at ca. 228,000 ybp, hominins at Bolomor Cave butchered, burned, and consumed large numbers of T. hermanni tortoises (Blasco 2008). In the Middle East, during a later timeframe, the late Epipaleolithic Natufian culture in Israel also utilized T. graeca extensively for symbolic and consumptive feasting, and perhaps for medicinal purposes (Grosman et al. 2008; Munro and Grosman 2010). These authors documented a Natufian female shaman’s ceremonial grave from 12,000 ybp containing over 50 sacrificed whole tortoises placed next to her body (with her head resting on a tortoise shell), and over 5500 bone fragments from over 70 butchered and roasted tortoises interred around her burial site. Clearly, tortoises were highly favored consumption resources in this early prehistoric society.

Asia. — Modern chelonophagy and exploitation by humans in many Asian countries, notably China, represents one of the main current threats to turtle biodiversity around the world (van Dijk et al. 2000; Turtle Conservation Coalition 2011). Originally coined the “Asian Turtle Crisis,” extensive consumption in China leading to widening trade routes from Southeast Asia and rapid trade globalization have extended the reach of Chinese demand beyond Asia, to all other continents where turtles occur. However, chelonophagy in Asia did not start in China, but rather with the first migrations of hominins and humans into southern Asia. In fact, the sequential extirpation of giant Megalochelys tortoises from various islands in the Indo-Australian Archipelago during the Pleistocene is generally interpreted as a specific indicator for the migratory arrival of early hominins, Homo erectus, gradually spreading across the Archipelago (Sondaar 1981, 1987; van den Bergh 1999; van den Bergh et al. 2009). All continental taxa of giant Megalochelys tortoises in the Sivaliks of India went extinct by the Early Pleistocene, and insular taxa also went gradually extinct in most of the Archipelago, surviving into the Middle Pleistocene only on Timor. By the Late Pleistocene, there were evidently no more giant tortoises anywhere in the South Asia and Southeast Asia regions. At a rockshelter site in peninsular Thailand dated at ca. 43,000 to 27,000 ybp, extensive remains of exploited chelonians revealed only still-extant species, with nearly all of them freshwater turtles of the families Geoemydidae (including Cuora amboinensis, a semi-terrestrial species) and aquatic Trionychidae (Mudar and Anderson 2007). There were only a few individuals of Indotestudo elongata, a smaller terrestrial tortoise with a carapace length of only about 27 cm. The proportion of chelonian bones in relation to other mammalian remains indicated that turtles and tortoises formed a very significant portion of the diet of these people, but easily-collected tortoises were no longer apparently as abundant in the local fauna. By the Holocene, smaller semi-terrestrial leaflitter turtles and aquatic turtles were sometimes the only chelonians found in some archaeological sites, such as in late Pleistocene archaeological deposits (ca. 13,000–7000 ybp) at Niah Cave in the lowlands of Borneo (Pritchard et al. 2009). Their analysis revealed that of the several identifiable turtle species utilized there at that time, all were geoemydids (Cyclemys dentata, Notochelys platynota, Heosemys spinosa) and trionychids (Amyda cartilaginea, Dogania subplana). There were no tortoise bones found in the deposits, probably a good indicator that large tortoises (Manouria emys, carapace length to ca. 60 cm) had either already been extirpated or did not occur in these lowland regions. In tropical forested Cambodia, from 2450 to 1450 ybp (500 BC to 500 AD), people at Phum Snay gathered and utilized many more large and easilycollected forest tortoises (Manouria emys) than more elusive river turtles, such as Batagur borneoensis and Amyda cartilaginea (O’Reilly et al. 2006). The most striking associations come from China, which affirm the longstanding cultural importance of turtles in that country. In early Neolithic China, at about 8550–8150 ybp (6600–6200 BC), turtle shells of the extant terrestrial geoemydid turtle, Cuora flavomarginata, were often associated with human burials (Li et al. 2003). Several turtle plastra inscribed with primitive proto-writing or reconstructed shells filled with colored pebbles that seemed to denote a special status were often placed strategically around the head or legs of buried people. One adult man whose head was missing instead had eight turtle shells (carapace and plastron) placed where the head should have been (Li et al. 2003). Turtles have long been revered and utilized in Chinese culture, and this pattern has extended and expanded into the present. Turtles and tortoises in modern China are now venerated and exploited not only for food consumption, but also for conversion into traditional medicinal products and use as high-end status pets, leading unfortunately to increasingly severe threat levels to their continued survival and a growing globalization of unsustainable turtle trade (van Dijk et al. 2000; Turtle Conservation Coalition 2011). Australia and the Pacific. —The giant horned turtles of the family Meiolaniidae were similarly apparently affected primarily by human overexploitation. Although the continental species in Australia may have also been affected by the gradual aridification of their habitat, they were probably affected more by human exploitation, similarly to the documented extirpation of the Australian continental megafauna at around 46,000 ybp (Flannery 1994). On their last Pacific island refugia, the last of the Meiolaniidae went extinct as a result of consumptive exploitation by humans, as noted by White et al. (2010), who documented finds of butchered meiolaniid bones in midden deposits from the Late Holocene. North America and the Caribbean. — As in Asia and Australasia, the disappearance of large terrestrial tortoises in the New World coincided with the arrival of humans. In addition to circumstantial evidence, Late Pleistocene and Early Holocene extinctions of giant North American continental tortoises, such as Hesperotestudo crassiscutata, were often associated with evidence of human exploitation, including a find from 12,000 ybp of a large individual killed by a wooden stake (Clausen et al. 1979; Holman and Clausen 1984). In addition, there was human exploitation of Gopherus tortoises by various Paleo-Indian cultures, including Clovis people, at about 11,200 ybp (Tuma and Stanford 2014). Not only did Clovis people exploit turtles and tortoises, but they constituted the fifth most frequent animal type found at their sites (found in 30% of sites), after mammoths (in 79% of sites), bison (52%), ungulates (45%), and rodents (39%), indicating the importance of chelonians in Clovis diet (Waguespack and Surovell 2003). Concurrent climate change may also have contributed to the vulnerability of these species by first reducing their populations before humans delivered the final extinction blow, but they were definitely exploited. A similar scenario of worsening climate with colder winters associated with human exploitation has been hypothesized for the extinction of the smaller southwestern tortoise species Hesperotestudo wilsoni at about 11,000 ybp (Moodie and Van Devender 1979). On the other hand, extirpation of the somewhat larger stillextant Bolson Tortoise, Gopherus flavomarginatus, from its Pleistocene distributional extent in Texas, Arizona, and New Mexico, was most likely caused by human exploitation (Morafka 1988; Truett and Phillips 2009), leaving it restricted and endangered in its current refuge in Mapimí in Mexico. In addition to tortoises, many species of aquatic turtles and small terrestrial box turtles were utilized by native Paleo-Indians of the North American Holocene (Archaic Period). These turtles were common in shell heap middens located in regions more northerly than the northern-most distributional extent of tortoises, in colder climatic zones such as around the Great Lakes and in New England (Adler 1968, 1970; Rhodin and Largy 1984; Rhodin 1986, 1992, 1995). Further, Adler (1970) also documented the gradual regional extirpation of terrestrial Box Turtles (Terrapene carolina) by Native Americans in northern New York State from about 3500 BC through ca. 1700 AD. Of all the Emydidae, Terrapene spp. are the most tortoiselike and terrestrial, reinforcing the pattern of easier and preferential human exploitation and chelonophagy of terrestrial chelonians.

In the Caribbean, the stratigraphic and geographic distribution of tortoises suggests wide Pleistocene dispersal throughout the area, followed by extirpation on the larger Greater Antilles islands, with relictual Holocene species remaining only on smaller and isolated or inhospitable islands such as Mona, Navassa, Sombrero, Middle Caicos, Grand Turk, and the Bahamas (Pregill 1981; Franz and Franz 2009; Steadman et al. 2014; Hastings et al. 2014). For example, Pregill (1981) documented no Late Pleistocene tortoises present on Puerto Rico; however, giant tortoises persisted into the Late Pleistocene or possibly the early Holocene on nearby Mona as well as several other small isolated islands.

In the Bahamas, on Abaco Island, Lucayan Taíno people arrived at ca. 950 ybp and the endemic tortoise, Chelonoidis alburyorum, was consumed into extinction by ca. 780 ybp (1170 AD) (Steadman et al. 2014; Hastings et al. 2014). In the Turks and Caicos islands, giant tortoises persisted into near-historic times, as late as ca. 1200 and 1400 AD, respectively, and were extirpated through direct human consumption by the Taíno and Meillac people (Carlson 1999; Franz et al. 2001). MesoAmerica and South America. — There are few records of Pleistocene and Holocene fossil turtles or tortoises from MesoAmerica or South America. There is an undescribed giant Hesperotestudo recorded from El Salvador in MesoAmerica, and an undescribed giant Chelonoidis from Curaçao offshore from Venezuela, but neither was associated with human habitation sites. Only one distinct fossil species has been verified from continental South America, Chelonoidis lutzae from the Late Pleistocene of Argentina, at ca. 22,000 ybp, probably preceding the arrival of humans. However, the Early Holocene habitation site of Caverna da Pedra Pintada, dated at ca. 11,700–9880 ybp and located along the Rio Amazonas in the lower Amazon basin, contained many bones of exploited turtles and tortoises (Roosevelt et al. 1996; Oliver 2008). Unfortunately, these bones have apparently not yet been identified, being described simply as Testudinidae (in our opinion, probably extant Chelonoidis carbonaria and/or C. denticulata) and Pleurodira (probably extant Podocnemis expansa and/or P. unifilis). Giant Tortoises as Megafauna Recent extensive global Pleistocene and Holocene megafaunal mammalian extinction modelling analysis by Sandom et al. (2014) has provided strong evidence of the predominant association of these extinctions with hominin and human paleobiogeography rather than climate change. This was especially striking for the Americas and Australia, areas where modern humans (H. sapiens) arrived without prior presence of prehuman hominins (H. erectus, H. neanderthalensis). In Eurasia there was at most some weak additional glacialinterglacial climate-associated influence on these extinction patterns. The patterns of giant tortoise extinctions are similar in scope and details to the widespread mammalian megafaunal extinctions of the Pleistocene and Holocene, and also suggestive of significant human influence. For analytical reviews and examples of the dynamics and specifics of these extinction events and human-induced extirpation patterns among other vertebrates, notably mammalian herbivores and other megafauna, see the following works (MacPhee 1999; Barnosky et al. 2004; Haynes 2009; Turvey 2009; van der Geer et al. 2010). Although none of these reviews provide any in-depth discussion concerning the similar extinction patterns of tortoises, they are useful in reviewing data regarding the competing (but not mutually exclusive) theories of Pleistocene human exploitation and overkill vs. climate change as causes for these extinctions. Extinctions of non-chelonian reptiles during the Pleistocene and Holocene have been documented by Case et al. (1998), who reported extensive patterns of reptilian extinctions over the last 10,000 years, but focused primarily on lizards, with only brief passing reference to a few tortoises that also went extinct. Our hypothesis regarding exploitation of giant tortoises is supported by the work of Surovell et al. (2005), who analyzed similar patterns of exploitation of giant proboscideans (elephants and mammoths). Their conclusion was that the archaeological record of human subsistence hunting of proboscideans was primarily located along the advancing edges of the human range, suggesting that human range expansion was associated with regional and global overkill of these animals, and that proboscideans succeeded in surviving essentially only in refugia inaccessible to humans. In our opinion, giant tortoises were probably extirpated in much the same way, being easier than giant proboscideans to collect and process, leading to the relatively rapid and expanding extinction of these species in the face of spreading humanity, surviving into Modern times only on a few isolated and distant oceanic islands beyond the reach of early hominins.

However, there are clear differences between the ecology of mammalian megafauna and of large tortoises. The poikilotherm physiology of tortoises not only allows them to survive extended periods without food, water or optimal temperatures, but also allows a much larger “standing crop” or biomass of tortoises than mammals for the same amount of primary production by the vegetation (Iverson 1982). Large compact aggregations of up to thousands of now-extinct giant Cylindraspis tortoises were described from Rodrigues in the Mascarenes upon first arrival of humans (Leguat 1707) (see Fig. 14), and present populations of Chersina angulata on Dassen Island in South Africa (Stuart and Meakin 1983), and Aldabrachelys gigantea on Aldabra (Coe et al. 1979), indicate a high potential biomass and carrying capacity for tortoises, particularly in the absence of mammalian herbivore competitors.

Associated with this physiology, however, are slow growth rates and late maturity, usually on the order of 10 to 25 years for medium and large tortoises. High hatchling and juvenile mortality rates are offset by longevity and persistent reproduction, often for several decades, of the individuals that reach maturity (Bourn and Coe 1978; Swingland and Coe 1979). Population modeling has, however, documented that such life histories are highly susceptible to the impacts of increased mortality of mature adults (Doroff and Keith 1990; Congdon et al. 1993, 1994), in effect leading to depleted populations within a few generations of exploitation. Migration and movement patterns of tortoises are generally insufficient to repopulate such depleted populations if adult tortoise mortality rates remain elevated through continued offtake by human hunter-gatherers, as evidenced by the failure of Amazonian tortoises (Chelonoidis denticulata and C. carbonaria) to persist within the daily hunting perimeter (8–10 km) around Amerindian villages (Souza-Mazurek et al. 2000; Peres and Nascimento 2006). Considering that an individual tortoise is at risk of detection by a human hunter effectively any day throughout its entire life, and that humans (and their hunting dogs) tend to look out for tortoises even when focused on hunting or gathering other species, few tortoises are likely to escape detection and predation by humans, with population collapse and species extinction only a matter of time.

Whether extinctions of these fossil chelonian taxa were primarily caused by prehistoric hominin and human overexploitation or climate change, or both working in concert, remains uncertain in most cases. For mammals these questions have generally been analyzed in association with body size, with mammalian megafauna (defined as having a body mass either ≥ 10 kg or ≥ 44 kg [100 lbs]) much more likely to have been overexploited by humans (Dirzo et al. 2004; Barnosky et al. 2004; Sandom et al. 2014). Since body size of turtle species is therefore relevant to this question (i.e., which chelonians could also be considered “megafauna”), we record approximate straight-line carapace length (CL) or a descriptive size of the species when available.

As a comparative reference, extant giant Aldabra Tortoises (Aldabrachelys gigantea) with a CL of ca. 39– 40 cm have a body mass of about 10 kg, those with a CL of ca. 59–60 cm have a body mass of about 44 kg, and those with a CL of ca. 100 cm have a body mass of about 156 kg, with large individuals of about 127 cm CL reaching a body mass of about 280 kg (Aworer and Ramchurn 2003)

Hypothesis:

Travis (Meatrition):

Turtles and tortoises had hard shells limiting their predation from other species. However, hominids could walk around and easily collect them, and then crush their small shells on rocks. That percussion could have also kickstarted an opposite rock-to-shell action, which led to further improvements in percussion and lithic technologies as well as cognitive growth, planning, and tool use. Tortoises could have provided a key food source for these early carnivorous apes that gave them key skills and brain growth that led to larger and more complex megafauna hunting. In a paleoanthropological world between 'scavenging' and 'hunting' - turtle 'gathering' can easily explain early carnivory in hominids.

One interesting issue is that turtles and tortoises are low fat. These small turtles (about a kg or less) had these results: The body without shell differed in fat content between species (tortoises 2.7 ± 2.2% DM; n = 48 versus aquatic turtles 12.0 ± 4.6% DM; n = 31).

The site of Blombos Cave (BBC), Western Cape, South Africa has been a strong contributor to establishing the antiquity of important aspects of modern human behaviour, such as early symbolism and technological complexity. However, many linkages between Middle Stone Age (MSA) behaviour and the subsistence record remain to be investigated. Understanding the contribution of small fauna such as tortoises to the human diet is necessary for identifying shifts in overall foraging strategies as well as the collecting and processing behaviour of individuals unable to participate in large-game hunting. This study uses published data to estimate the number of calories present in tortoises as well as ungulates of different body size classes common at South African sites. A single tortoise (Chersina angulata) provides approximately 3332 kJ (796 kcal) of calories in its edible tissues, which is between 20 and 30% of the daily energetic requirements for an active adult (estimated between 9360 kJ [3327 kcal] and 14,580 kJ [3485 kcal] per day). Because they are easy to process, this would have made tortoises a highly-ranked resource, but their slow growth and reproduction makes them susceptible to over-exploitation. Zooarchaeological abundance data show that during the ca. 75 ka (thousands of years) upper Still Bay M1 phase at BBC, tortoises contributed twice as many calories to the diet relative to ungulates than they did during the ca. 100 ka lower M3 phase. However, in spite of the abundance of their fossils, their absolute caloric contribution relative to ungulates remained modest in both phases. At the end of the site's MSA occupation history, human subsistence strategies shifted to emphasise high-return large hunted mammals, which likely precipitated changes in the social roles of hunters and gatherers during the Still Bay.

From the intro of the paper:

As an addition to the annual checklist of extant modern turtle taxa (Turtle Taxonomy Working Group [TTWG] 2014), we here present an annotated checklist of extinct Pleistocene and Holocene turtle and tortoise species that existed in relatively recent times, prior to 1500 AD, during the history of the rise and global spread of humanity and concurrent global climatic and habitat changes. These species, recorded from archaeological and paleontological sites from the Pleistocene and Holocene epochs (Quaternary period), approximately the last 2.6 million years, are currently considered to be valid, and not synonymous with modern (post-1500 AD) taxa. These fossil species, including some unnamed taxa of indeterminate or undescribed generic or specific allocation, represent the majority of the chelonian diversity that has gone extinct relatively recently. Many of these taxa were likely extirpated by anthropogenic exploitation over the relatively long prehistory of earlier hominin (e.g., Homo erectus, H. neanderthalensis, and others) and later human (H. sapiens) exploitation of turtles and tortoises. In addition, many were also likely affected by global and regional climate change and cycles of warming and cooling and habitat alterations, such as those associated with glacial and interglacial periods and sea level changes and aridification, or stochastic events such as volcanism. As such, these recently extinct fossil species and taxa are eminently relevant to our understanding of distribution and extinction patterns among modern chelonians. Additionally, they broaden our awareness of the baseline and extent of turtle richness and diversity that existed at the early beginnings of humanity’s utilization and consumption of turtles—exploitation that greatly increased with the rapid global expansion of humanity. Of notable interest in this fossil checklist are the very recent, apparently human-induced extinctions of giant tortoises of the family Testudinidae, as well as giant horned terrestrial turtles of the extinct family Meiolaniidae. Among the Testudinidae are the Madagascan giant tortoises, Aldabrachelys abrupta and A. grandidieri, that went extinct in about 1200 AD and 884 AD, respectively, not long after humans reached Madagascar ca. 2000 years ago (Pedrono 2008). Additionally, some large insular species of Chelonoidis from the Bahamas region of the Caribbean West Indies were eaten into extinction by pre-Columbian natives as late as ca. 1170–1400 AD (Carlson 1999; Franz et al. 2001; Hastings et al. 2014). Among the Meiolaniidae, we have the remarkable giant terrestrial horned turtle, Meiolania damelipi from Vanuatu in the southern Pacific Ocean, also eaten into extinction by humans by about 810 BC (White et al. 2010), as well as an unnamed giant horned turtle from nearby New Caledonia, that went extinct as recently as about 531 AD (Gaffney et al. 1984). This unnamed and vanished species was apparently the last surviving member of this most impressively distinct and ancient family of giant horned terrestrial turtles. Several recent phylogenies suggest that the Meiolaniidae branched off as a separate clade of turtles before the Cryptodira– Pleurodira split (e.g., Joyce 2007; Sterli and de la Fuente 2013), but others (e.g., Gaffney 1996; Gaffney et al. 2007; Gaffney and Jenkins 2010) place them among the Cryptodira. In either case, their recent extinction was indeed major, not just for their disparate and bizarre morphology, but also because had they persisted, they would have been one of the most evolutionarily and phylogenetically distinct lineages of surviving chelonians—truly a monumental loss. It is our hope that this additional checklist will increase our focus and understanding of these turtles and tortoises lost to extinction during relatively recent times, and that we will gain a greater appreciation for chelonian diversity and a greater sense of loss that so many giant tortoises and horned turtles and other amazing species have been lost forever to extinction. Hopefully this will increase our resolve to assure that we lose no more, whether to anthropogenic means or climate change, and increasingly inspire our conservation ethic to continue to work together for their preservation and protection.