Recent History

January 3, 1923

Elliott P. Joslin

The Treatment of Diabetes Mellitus

Joslin's food values important to the treatment of diabetes lists many zerocarb foods such as meat, chicken, bacon, cheese, butter, oil, fish, and broth. He jokes later that it is impractible to show carb counts in other foods because they're effectively banned.

"Caloric Values which Every Doctor Should Know by Heart.

The quantity of carbohydrate, protein and fat found in an ordinary diet must be known by a physician if he wishes to treat a case of diabetes successfully. If he cannot calculate the diet he will lose the respect of his patient. The value of the different foods in the diet can be calculated easily from the diet Table 165. This is purposely simple, because a diet chart, to be useful, must be easily remembered . With these food values as a basis it is possible to give a rough estimate of the value and composition of almost any food . Various foods are also classified according to the content of carbohydrate (see p.435) in 5, 10, 15 and 20 per cent groups, and the lists are so arranged that those first in each group contain the least, those at the end the most . This is a practical and sufficiently accurate arrangement , because except in the most exact experiments the errors in the preparation of the food are too great to warrant closer reckoning. It is practically impossible , except when accurate analyses of the diet are made , to reckon the car bohydrate for the twenty - four hours closer than within 5 to 10 grams , and we had best acknowledge that fact . It is really surprising , however , how reliable the figures are if we do not push the matter to extremes . For example, the protein was analyzed in 10 portions of cooked lean meat, similar to 10 other portions served the same day at the New England Deaconess Hospital. In these analyses it was found that the protein content was 30 per cent .

Repeatedly physicians have requested me to arrange the above table in terms of household measures. To a considerable extent this is impracticable because the diabetic diet deals with so small a quantity of carbohydrate."

February 9, 1924

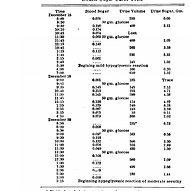

Hypoglycemic symptoms provoked by repeated glucose ingestion in a case of renal diabetes by R.B. Gibson, Ph.D and R.N. Larimer, M.D., Iowa City

Hypoglycemic symptoms provoked by repeated glucose ingestion in a case of renal diabetes - A case study of using repeated bouts of 50 grams of carbs shows the danger of hypoglycemia "consisting of burning and flushing of the face, weakness, tremor and sweating. The second shock was the more severe of the two."

HYPOGLYCEMIC SYMPTOMS PROVOKED BY REPEATED GLUCOSE INGESTION IN A CASE OF RENAL DIABETES R. B. Gibson, Ph.D., and R. N. Larimer, M.D., Iowa City

One of us (R. B. G.), in November last, reviewed the chemical findings in a case from our diabetic clinic before the Iowa Clinical Medical Society. Interest in the case centered in the fact that a final diagnosis of what was otherwise a case of pronounced renal diabetes could not be made because the sugar curve indicated a deficient glycogenesis of the mildly diabetic type. A study of the effects of a repeated ingestion of glucose on the sugar curve by Hamman and Hirschman was recalled, and we predicted in our report that a decisive differentiation might be obtained if we employed the double sugar curve test in this case. The patient was requested to return for further observation, and promised to come to the clinic in January of this year.

We have in the clinic, at the present time, a second patient with a fasting hypoglycemia and a glycosuria of long standing which does not respond to diabetic management. The data presented in this communication were obtained in this case. Glycogenesis is stimulated by glucose ingestion, as is indicated by the rapid fall of the blood sugar from the peak of the curve (usually forty-five minutes) to a figure at the end of two hours almost always less than the fasting control observation. A second administration of glucose brings about a yet more rapid removal of sugar from the blood stream and a consequent lowering of the sugar curve. The desugarized diabetic patient may show an effect similar to the normal person, but of much less degree (one case, Hamman and Hirschman). When tried in our case, the effect of the double sugar curve test was so great that hypoglycemic symptoms were observed in two out of three trials.

REPORT OF CASE Mrs. B., aged 30, white, weight 110 pounds (50 kg.) (best weight 115 pounds [52 kg.] ten years ago) was admitted to the hospital with a history of glycosuria of ten years' standing. This had been discovered by a urine examination during the first of her two pregnancies. She had never had other symptoms of diabetes except for some pruritus seven years ago; she had dieted off and on since that time. The condition seemed to be familial, the patient stating that she had one sister surely and one probably glycosuric patients without other symptoms; however, she had no knowledge of glycosuria in either of her parents. The patient was placed on a diet of 50 gm. of protein, 50 gm. of carbohydrate, and 125 gm. of fat; on this, she excreted from 4.5 to 8.5 gm. of glucose daily. Her blood uric acid was 3 mg., and blood urea nitrogen, 18 mg. Fasting blood sugar determinations or figures obtained two hours after meals were always hypoglycemic. The results of our tests with the double sugar curve are given in the accompanying table.

Definite hypoglycemic symptoms were obtained in the first and third trials; they were identical with the several mild insulin reactions which we have observed in our diabetic patients, consisting of burning and flushing of the face, weakness, tremor and sweating. The second shock was the more severe of the two; the patient was completely relieved in fifteen minutes when given 100 c.c. of orange juice. The lowering of the leyel of the entire curve in the third trial is in accord with the experience that glycogenic effects may become more pronounced if the ordinary procedure is repeated without a sufficient number of days elapsing between tests. When questioned as to the occurrence of similar attacks at home, the patient stated that she had experienced such of milder degree, but could not associate these with any definite circumstance. One sister had like attacks. It seems likely that hypoglycemic symptoms not artificially produced are a definite clinical entity.

In explanation of a diminished glycogenesis in pronounced renal diabetes, it was stated, in the paper referred to above, that "It is quite possible that glycogenesis in our case may be functionally diminished because of the rapid removal of glucose through the kidneys; if so, repeated administration of glucose might so stimulate the glycogenic power fhat a normal or subnormal sugar curve will result." Since this report was submitted for publication, threshold hypoglycemic symptoms with a blood sugar of 0.045 per cent, have been induced in our first patient; the maximum hypoglycemic effect is quite transient.

December 1, 1927

Dietary Factors that Influence the Dextrose Tolerance test - A preliminary study - by J. Shirley Sweeney, M.D.

Sweeney studies healthy young people to see how feeding them a certain macronutrient influences the results of a glucose tolerance test, and proves that carbohydrates sensitize the body to future carbohydrates, while fat and starving create an insulin resistance effect where blood sugar stays high after a sudden assault of glucose.

The current explanation of this phenomenon (Macleod) is that the first dose of glucose sensitizes the insulin-secreting mechanism, so that in response to the second dose the islet cells secrete insulin more readily and more abundantly at a lower level of hyperglycaemia. On the basis of this explanation Sweeney, in 1927, attempted to explain the variations in sugar tolerance found in normal subjects on different diets. Using the ordinary glucose tolerance test as a guide, he investigated the sugar tolerance of healthy individuals during starvation, on a fat diet, on a protein diet, and on a carbohydrate diet. He found that protein had little effect; that fat diets and starvation diminished sugar tolerance; and that carbohydrate diets improved sugar tolerance. Sweeney considered that the diminished sugar tolerance was due to the impaired sensitivity of the insulin-secreting apparatus, consequent upon the absence of the stimulus of carbohydrate ingestion, and that the improved tolerance was the result of the increased sensitivity of this mechanism, owing to greater stimulation.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2444943/pdf/brmedj07161-0009.pdf

December 1927

DIETARY FACTORS THAT INFLUENCE THE DEXTROSE TOLERANCE TEST - A PRELIMINARY STUDY

Abstract

The dextrose tolerance test is now being extensively employed as a diagnostic procedure. It is most beneficially used in the differentiation of mild diabetes mellitus and renal diabetes. It is also being used, and is believed to be of diagnostic value, in many pathologic conditions, such as encephalitis, malignant tumor, pituitary and thyroid dysfunctions and nephritis.

Although it is definitely established as a diagnostic procedure, there is some diversity of opinion concerning what constitutes a normal response to the oral administration of dextrose. Some writers state that in a healthy person there may be a postprandial rise in blood sugar of from 14 to 16 per cent and a return to the normal within two hours. There are other writers who consider a postprandial hyperglycemia of 20 per cent within normal limits. It is generally believed that the persistence of the postprandial hyperglycemia is of more diagnostic significance than the degree of hyperglycemia. In early cases of diabetes the blood sugar curve rises higher, stays up for a longer time and does not return to normal for several hours. Macleod says that "slight deviations from the normal must not be given too much weight in diagnosis, since they may occur in other diseases or even in perfectly normal persons." All who have studied dextrose tolerance curves have noted the variability exhibited by normal persons, to say nothing of those who are diseased. These variations have been discussed and explained in different ways.

It occurred to me that perhaps the character of the food and the amount of water that a person had been consuming for a few days prior to the time the tolerance test was made might be factors that would influence the dextrose tolerance curve. If these factors should prove to be capable of altering a tolerance curve, they could be controlled. This would eliminate some of the confusing variability that is so frequently observed. It was these thoughts that lead to the following experiments.

Young, healthy, male medical students were used to study the effect of different preceding diets. Four groups were formed. The subjects in one group were given a protein diet, those in another a fat diet, those in a third a rich carbohydrate diet, and those in the fourth group were not given any food—the starvation group. Those on the protein diet received only lean meat and the whites of eggs. The students on the fat diet received only olive oil, butter, mayonnaise made with egg yolk, and 20 per cent cream. Those in the group fed on carbohydrates were allowed sugar, candy, pastry, white bread, baked potatoes, syrup, bananas, rice and oatmeal. These diets were followed for two days. Meals were taken at the usual hours, and eating between meals was allowed, provided the diets were followed. Those in the starvation group did without food for two days.

On the morning of the third day, each student was given by mouth 1.75 Gm. of dextrose per kilogram of body weight, on an empty stomach. Determinations of blood sugar were made from samples of venous blood removed immediately before the dextrose was given, and at 30, 60 and 120 minute intervals following its administration. I made all determinations of blood sugar by the Folin-Wu method.

A better comparison of these groups is obtained by examining table 5 and chart 5 in which are contained the average or type curves of each group. It will be noted that those students who were on the carbohydrate diet exhibited a marked increase in sugar tolerance and those on a protein diet a slight decrease in tolerance, while those who were placed on the fat diet and those who were starved manifested a definite decrease in sugar tolerance. The differences in the average fasting blood sugars are noteworthy. The blood sugar in those of the protein and starvation groups was distinctly lower than that of the members of the fat and carbohydrate groups.

Because of the great difference in these groups, those students on the fat diet and those in the starvation group who showed the most extreme responses were placed on the carbohydrate diet. Similiarly, those in the carbohydrate group who showed an extreme response were placed on starvation restriction. This was obviously done to determine whether the curve of a person could be changed significantly by diet. The results are presented in table 6 and in charts 6 and 7.

Comparison of the curves of these five students is striking. The curves of all who had been placed on carbohydrate diets manifested a definite increase in their sugar tolerance. When three of these (the three most extreme) were placed on starvation restrictions, the curves were notably abnormal ; there was a marked postprandial hyperglycemia. which persisted at the end of two hours ; in other words, what was an increased sugar tolerance following the carbohydrate diet became a definitely decreased tolerance following two days of starvation. The remaining two persons who were placed on the fat diet showed a similar decreased tolerance. It should be stated that an interval of at least one week was allowed between the tolerance tests performed on the same subject.

January 1, 1928

Diet, delusion and diabetes

Dr Sansum increases the carb content in his Type 1 Diabetics to 245 grams per day because it was shown that a high carb diet improved glucose tolerance (but not risk of disease).

Physicians were slow to appreciate that insulin allowed the proportion of carbohydrate in the diet to be increased, for, as Himsworth said, ‘a well-founded theory directs that the carbohydrates in the diabetic’s diet must be curtailed if health is to be preserved’. On the other hand, as he continued, ‘a brilliant piece of clinical empiricism produces irrefutable proof that a liberal allowance of carbohydrate acts favourably on the diabetic’s health’ [17]. This empiricism began in 1926, when a high carbohydrate diet was first shown to improve glucose tolerance in healthy individuals [18]. Noting this, William Sansum promptly increased the carbohydrate content of the diet of his Californian patients; a typical recommendation might include 2,435 calories, 245 g of carbohydrate (40% of energy requirements), 124 g of fat and 100 g of protein [19].

January 5, 1928

Helge Ingstad

The Land of Feast and Famine - The Barren Ground Indians

The diseases of the white men can be blamed for the general ill health of the Indians, but adopting a life of flour has even worse consequences for chronic disease according to Ingstad.

The Indians seldom live to a ripe old age. It is their custom to bury the dead and erect a circle of tall pointed poles about the grave. If the death takes place in the winter-time, the corpse is preserved in a wooden coffin, and later, when the frost has gone out of the ground, the relatives provide it with burial, even though they must make a long and arduous journey for this purpose.

Formerly the aged and others unfitted to make the long journeys were left behind in the wilderness. This custom is no longer adhered to. Even so, it is as pathetic today as before for an Indian to become old and infirm. By and large, he receives full sympathy from the others, but he who must remain at home with the womenfolk, whilst the hunters are afield after the caribou, no longer enjoys the respect of his fellows, and this is indeed a bitter fate for men who rank the honor of the hunter above all else in life.

In olden times the Indians were susceptible to various illnesses; amongst these may be mentioned the plague of boils. The malady still occurs, although to a lesser extent. The boils often appear on the hips and buttocks and I have seen them as large as clenched fists. It takes quite a long time to effect a cure.

The ancient illnesses are of little significance contrasted with the diseases derived from the white race. Thus tuberculosis has wreaked havoc with the Indians east of Great Slave Lake. Spasmodic epidemics of " flu " have broken out in their ranks and have brought death to many. Venereal diseases, on the other hand, are anything but common. In an earlier portion of this book I have spoken of the epidemics of coughing which break out in the spring of the year and often continue all through the summer months, disappearing as soon as cold weather sets in. These colds can hardly be due to infection from the outside, since they afflict even the Indians living in entirely isolated regions.

Like other primitive peoples, the Indians are lacking in physical resistance to the diseases of the white race. There are other factors, too, which play a definite part in the spreading of disease: the habit of spitting incessantly and the general uncleanliness of the Indians, to which may be added their spirit of resignation when illness begins to assume serious proportions. On the whole, the people east of Great Slave Lake have fared better than the tribes which, to a varying degree, have given up a healthy tepee-life and the food which the wilderness provides, in exchange for a life indoors and a diet of flour.

Ever since ancient times the Indians have had their own medicines prepared from weeds, roots, and bark, often administered to the accompaniment of certain rites. From an old Indian I once received the information that he knew about thirty different kinds of medicines, amongst these a poison which could kill a human being in the course of five minutes. Further than this he would say nothing, for an Indian guards his medical knowledge with the most scrupulous secrecy. How great a part mystic rites and possible frauds play in the cure it is, consequently, difficult to determine. One matter of significance in this connection is worth mentioning, however: the Indian is a most apt subject for all forms of suggestion.

In spite of the fact that the materia medico, of the Indians is so frequently cluttered up with superstition, there are reasons to suppose that a number of their medicines have various effects. It is a known fact, for example, that they have a practical means of abortion. For diarrhoea they use dried rushes. For urinary ailments they drink a broth made from the inner red bark of the willow. For scurvy they boil the needles of the dwarf spruce in water for a short time and drink the liquid. By boiling the inner bark of the larch they obtain an antiseptic, which is then placed upon the ailing part as hot as the patient can stand it. It seems not only to kill infection, but also to cause the wound to heal more rapidly than otherwise. For frost-bite they use the inner bark of the pine. This they chew into a pulp, which they then plaster over the frozen part. May I add that, after writing the above, I allowed an Indian to doctor one of my great toes which had become frozen, but that the inflammation had gone so far that perhaps the treatment of my medicine-man was not wholly to blame? In any event, the result was that Williams of the Royal Mounted Police was obliged to cut away a goodly portion of my toe.

Ancient History

8000

B.C.E.

Evolutionary and Population Genomics of the Cavity Causing Bacteria Streptococcus mutans

S. Mutans, the bacteria involved in creating cavities likely evolved and expanded with the population growth 10,000 years ago as humans started relying more on starches and sugars.

Streptococcus mutans is widely recognized as one of the key etiological agents of human dental caries. Despite its role in this important disease, our present knowledge of gene content variability across the species and its relationship to adaptation is minimal. Estimates of its demographic history are not available. In this study, we generated genome sequences of 57 S. mutans isolates, as well as representative strains of the most closely related species to S. mutans (S. ratti, S. macaccae, and S. criceti), to identify the overall structure and potential adaptive features of the dispensable and core components of the genome. We also performed population genetic analyses on the core genome of the species aimed at understanding the demographic history, and impact of selection shaping its genetic variation. The maximum gene content divergence among strains was approximately 23%, with the majority of strains diverging by 5–15%. The core genome consisted of 1,490 genes and the pan-genome approximately 3,296. Maximum likelihood analysis of the synonymous site frequency spectrum (SFS) suggested that the S. mutans population started expanding exponentially approximately 10,000 years ago (95% confidence interval [CI]: 3,268–14,344 years ago), coincidental with the onset of human agriculture. Analysis of the replacement SFS indicated that a majority of these substitutions are under strong negative selection, and the remainder evolved neutrally. A set of 14 genes was identified as being under positive selection, most of which were involved in either sugar metabolism or acid tolerance. Analysis of the core genome suggested that among 73 genes present in all isolates of S. mutans but absent in other species of the mutans taxonomic group, the majority can be associated with metabolic processes that could have contributed to the successful adaptation of S. mutans to its new niche, the human mouth, and with the dietary changes that accompanied the origin of agriculture.

Undoubtedly, one of the major challenges that S. mutans had to overcome as the carbohydrate content of the human diet increased was surviving at low pH. Although S. mutans does not constitute a significant proportion of the oral flora colonizing healthy dentition, it can become numerically significant when there is repeated and sustained acidification of the biofilms associated with excess dietary carbohydrates or impaired salivary function (Burne 1998).

Luxor, Luxor Governorate, Egypt

2475

B.C.E.

The Earliest Record of Sudden Death Possibly Due to Atherosclerotic Coronary Occlusion

WALTER L. BRUETSCH

The sudden death of an Egyptian noble man is portrayed in the relief of a tomb from the Sixth Dynasty (2625-2475 B.C.). Since there is indisputable evidence from the dissections of Egyptian mummies that atherosclerosis was prevalent in ancient Egypt, it was conjectured that the sudden death might have been due to atherosclerotic occlusion of the coronary arteries.

It may be presumptuous to assume that an Egyptian relief sculpture from the tomb of a noble of the Sixth Dynasty (2625-2475 B.C.) may suggest sudden death possibly due

to coronary atherosclerosis and occlusion. Much of the daily life of the ancient Egyptians has been disclosed to us through well-preserved tomb reliefs. In the same tomb that contains the scene of the dying noble, there is the more widely known relief "Netting Wildfowl in the Marshes." The latter sculpture reveals some of the devices used four thousand years ago for catching waterbirds alive. It gives a minute account of this occupation, which in ancient Egypt was both a sport and a means of livelihood for the professional hunter.

The relief (fig. 1), entitled "Sudden Death," by the Egyptologist von Bissing2 represents a nobleman collapsing in the presence of his servants. The revelant part of the explanatory text, as given by von Bissing, follows (translation by the author):

The interpretation of the details of the theme is left to the observer. We must attempt to comprehend the intentions of the ancient artist who sculptured this unusual scene. In the upper half (to the right) are two men with the customary brief apron, short hair covering the ears, busying themselves with a third man, who obviously has collapsed. One of them, bending over him, has grasped with both hands the left arm of the fallen man; the other servant, bent in his left knee, tries to uphold him by elevating the head and neck, using the knee as a support. Alas, all is in vain. The movement of the left hand of this figure, beat- ing against the forehead, seems to express the despair; and also in the tightly shut lips one can possibly recognize a distressed expression. The body of the fallen noble is limp. . . . Despite great restraint in the interpretation, the impression which the artist tried to convey is quite obvious. The grief and despair are also expressed by the figures to the left. The first has put his left hand to his forehead. (This gesture represents the Egyptian way of expressing sorrow.) At the same time he grasps with the other arm his companion who covers his face with both hands. The third, more impulsively, unites both hands over his head. ... The lord of the tomb, Sesi, whom we can identify here, has suddenly collapsed, causing consternation among his household.

In the section below (to the left) is shown the wife who, struck by terror, has fainted and sunk totheflor. Two women attendants are seen giving her first aid. To the right, one observes the wife, holding on to two distressed servants, leaving the scene. . . .

von Bissing mentions that the artist of the relief must have been a keen observer of real life. This ancient Egyptian scene is not unlike the tragedy that one encounters in present days, when someone drops dead of a "heart attack." The physician of today has almost no other choice than to certify the cause of such a death as due to coronary occlusion or thrombosis, unless the patient was known tohave been aflictedwith rheumatic heart disease or with any of the other more rare conditions which may result in sudden death.

Atherosclerosis among the Ancient Egyptians

The most frequent disease of the coronary arteries, causing sudden death, is atherosclerosis. What evidence is available that atherosclerosis was prevalent in ancient Egypt?

The first occasion to study his condition in peoples of ancient civilizations presented itself when the mummified body of Menephtah (approx.1280-1211B.C.), the reported "Pharaoh of the Hebrew Exodus" from Egypt was found. King Menephtah had severe atherosclerosis. The mummy was unwrapped by the archaeologist Dr. G. Elliot Smith, who sent a piece of the Pharaoh's aorta to Dr. S. G. Shattock of London (1908). Dr. Shattock was able to prepare satisfactory microscopic sections which revealed advanced aortic atherosclerosis with extensive depositions of calcium phosphate.

This marked the beginning of the important study of arteriosclerosis in Egyptian mummies by Sir Mare Armand Ruffer, of the Cairo Medical School(1910-11). His material included mummies ranging over a period of about 2,000 years (1580 B.C. - 525 A.D.).

The technic of embalming in the days of ancient Egypt consisted of the removal of all the viscera and of most of the muscles, destroying much of the arterial system. Often, however, a part or at times the whole aorta or one of the large peripheral arteries was left behind. The peroneal artery, owing to its deep situation, frequently escaped the em- balmer'sknife. Otherarteries,suchasthe femorals, brachials, and common carotids, had persisted.

In some mummies examined by Ruffer the abdominal aorta was calcified in its entirety, the extreme calcification extending into the iliae arteries. Calcified plaques were also found in some of the larger branches of the aorta. The common carotid arteries frequently revealed patches of atheroma, but the most marked atheroselerotic alterations were in the arteries of the lower extremities. The common iliae arteries were not infrequently studded with calcareous plaques and in some instances the femoral arteries were converted into rigid tubes. In other mummies, however, the same arteries were near normal.

What is known as Mdnekeberg's medial calcification was also observed in some of the mummified bodies. In a histologic section of a peronieal artery, the muscular coat had been changed almost wholly by calcification. In one of Ruffer's photographic plates, a part of a calcified ulnar artery is shown. The muscular fibers had been completely replaced by calcification.

In the aorta, as in present days, the atherosclerotic process had a predilection for the points of origin of the intercostal and other arteries. The characteristics and the localization of the arterial lesions observed in Egyptian mummies leaves litle doubt that atherosclerosis in ancient times was of the same nature and degree as seen in today's postmortem examinations.

As to the prevalence of the disease, Ruffer ventured to say that the Egyptians of ancient times suffered as much as modern man from arterial lesions, identical with those found in our times. Ruffer was well qualified to make this statement having performed many autopsies on modern Egyptians, Moslems, and other people of the Middle East. In going over his material and examining the accompanying photographic plates of arteries, one can have litle doubt that what Ruffer had observed in Egyptian mummies represented arteriosclerosis as it is known today.

Although the embalming left no opportunity to examine the coronary arteries inl mummified bodies, the condition of the aorta is a good index of the decree of atheroselerosis present elsewhere. In individuals with extensive atheroselerosis of the aorta, there is almost always a considerable degree of atherosclerosis in the coronary arteries. If Ruffer's statement is correct that the Egyptians of 3,000 years ago were afflicted with arteriosclerosis as much as we are nowadays, coronary occlusion must have been common among the elderly population of the pre-Christian civilizations.

Furthermore, gangrene of the lower extremities in the aged has been recognized since the earliest records of disease. Gangrene of the extremities for centuries did not undergo critical investigation until Cruveilhier (1791- 1873) showed that it was caused by atherosclerotic arteries, associated at times with a terminal thrombus.

SUMMARY

The record of a sudden death occurring in an Egyptian noble of the Sixth Dynasty (2625-2475 B.C.) is presented. Because of the prevalence of arteriosclerosis in ancient Egyptian mummies there is presumptive evidence that this incident might represent sudden death due to atheroselerotic occlusion of the coronary arteries.

Cairo, Cairo Governorate, Egypt

1580

B.C.E.

ON ARTERIAL LESIONS FOUND IN EGYPTIAN MUMMIES

Arteries of Egyptian mummies from 1580 B.C.E. to 525 A.D. have extensive calcification of the arteries, the same nature as we see today, and unlikely to be due to a very heavy meat diet, which was always a luxury in ancient Egypt. Instead, the diet was mostly a course vegetarian one.

DISCUSSION OF RESULTS.

Nature of the lesions. There can be no doubt respecting the calcification of the arteries, and that it is of exactly of the game nature as we see at the present day, namely, calcification following on atheroma.

The small patches seen in the arteries are atheromatous, and though the vessels have without doubt been altered by the three thousand years or so which have elapsed since death, nevertheless the lesions are still recognisable by their position and microscopical structure.

The earliest signs of the disease are always seen in or close below the fenestrated membrane,-that is, just in the position where early lesions are seen at the present time. The disease is characteiised by a marked degeneration of the muscular coat and of the endothelium. These diseased patches, discrete at first, fuse together later, and finally form comparatively large areas of degenerated tissue, which may reach the surface and open out into the lumen of the tube. I need not point out how completely this description agrees with that of the same disease as seen at the present time.

I have already mentioned the absence of leucocytes and cellular infiltration, and need not therefore return to it here.

In my opinion, therefore, the old Egyptians suffered as much as we do now from arterial lesions identical with those found in the present time. Moreover, when we consider that few of the arteries examined were quite healthy, it would appear that such lesions were as frequent three thousand years ago as they are to-day.

I do not think we can accuse a very heavy meat diet. Meat is and always has been something of a luxury in Egypt, and although on the tables of offerings of old Egyptians haunches of beef, geese, and ducks are prominent, the vegetable offerings are always present in greater number. The diet then as now was mostly a vegetable one, and often very coarse, as is shown by the worn appearance of the crown of the teeth.

Nevertheless I cannot exclude a high meat diet as a cause with certainty, as the mummies examined were mostly those of priests and priestesses of Deir el-Bahari, who, owing to their high position, undoubtedly lived well. I must add, however, that I have seen advanced arterial disease in young modern Egyptians who ate meat very occasionally. In fact, my experience in Egypt and in the East has not strengthened the theory that meat-eating is a cause of arterial disease.

Finally, strenuous muscular exercise can also be excluded as a cause, aa there is no evidence that ancient Egyptians were greatly addicted to athletic sport, although we know that they liked watching professional acrobats and dancers. I n the ca6e of the priests of Deir el-Bahari, it is very improbable, indeed, that they were in the habit of doing very hard manual work or of taking much muscular exercise.

I cannot therefore at present give any reason why arterial disease should have been so prevalent in ancient Egypt. I think, however, that it is interesting to find that it was common, and that three thousand years ago it represented the same anatomical characters as it does now.

FIG. 1.-Pelvic and arteries of thigh completely calcified (XVIlIth-XXth Dynasty).

Fro. 2.-Completely dcifiedprofundaarteryaftersoakinginglycerine(XXIstDynasty). FIQ. 8.-Partly calcified aorta (XXVIIth Dynasty).

Fro. 4.-Calcified patches in aorta (XXVIIth Dynasty).

Fio. 5.-Calcified atheromatous ulcer of subclavian artery (XVIIIth-XXth Dynasty). Fro. &-Patch of atheroma i n anterior tibia1 artery (glycerine). The centre of the patch

is calcified (XXIst Dynasty).

FIG. 7.-Atheroma of brachial artery (glycerin) (XXIst Dynasty).

Fro. &-Unopened ulnar artery, atheromatous patch shining through (glycehne) (XXIst Dynasty). 31

FIG. 9.-Section through almost completely calcified posterior peroneal artery (low power). Van Gieson staining. a,al, n2, Remnants of endothelium and

fenestrated membrane. b, Calcified patches.

Many more are seen.

Same stain. (Leitz, Oc. 1, x &.)

FIG. 10.-Section

FIG. 11.-Section m(Leitz, Oc. 1, x *.)

a,Remains of endothelium.

b, Fenestrated membrane.

c, Muscular coat.

d,f,Membrane coat undergoing degenerntion.

e, Completely degenerated remnants of muscular coat.

atheroniatous patch of n h a r artery. Same stain. (Leitz, (Reference letters the same as in Fig. 11.)

FIG. 12.-Section Oc. 1, x fa.)

through calcified patch of ulnar artery. a,d, Calcified patches.

b, Partially calcified m wular coat. c, Annular muscular fibre.

through atheromatous patch of anterior tibia1 artery. Same stain through

FIG. 13.-Section at edge of atheromatous patch. Hreniatoxylin stain (Leitz, Oc. 1, XTh.1 a,Leucocytes (1). The atheromatous part on the left stains intensely dark with hamatoxylin.