Total Entries: 1045

Select one of the above filters

Year Filter:

Grape Sugar Exports from US Ports in 1900

These maps show trends in the export flow of glucose from United States ports to the world from 1890 to 1910. Exporters shipped glucose (or “grape-sugar”) by the tens of millions of pounds throughout the later 1800s. The trade grew from three export ports in 1890 (Boston, New York, and Detroit) to six in 1910; it expanded from five global regional destinations to seven. In terms of quantity, the exports grew fifteen-fold from about 46 million to 728 million pounds in 1910. Some of the more notable trends are the increases in shipment to various South American countries by the early 1900s and shipments to new Asian markets beginning in 1905. The United Kingdom was such a large trading partner with the U.S. for glucose that their records offered more precision and, thus, the maps show direct flows to the UK while showing aggregated export streams to regions (Northern Europe, Southern Europe, South America) with less specificity in record keeping.

Because trade records provide a wide range of quantities per year, for the sake of reader legibility the maps represent proportions. For example, an arrow five-hatch-marks wide is five orders of magnitude greater than an arrow with one hatch mark, while the width of the five-hatch arrow is five times the width of the one-hatch arrow. Readers can thus view the maps to gain a sense of growth in export markets, relative quantities to various parts of the world, and sense of scale in the global marketplace for supposed adulterants.

The maps derive from government trade statistics that listed departure ports (export locations) and final destinations (import locations), but not together. For instance, while we know manufacturers shipped x pounds of glucose from New York in 1890, we do not know where, specifically, that specific quantity ended up. Therefore, the maps show the commodities shipped from individual U.S. ports to meet in the Atlantic before dispersing to final destinations.

In general, but not consistently, the government statistics used to construct theses maps documented foreign imports by country. Thus, in creating these maps the countries were aggregated into regions such as Northern Europe, Southern Europe, South America, Central America, Africa, and Asia. On the export side, various cities were aggregated into regions based on geographical proximity. The full data sets show specific nations.

As with shipments of raw oleo oil, notable trends for oleomargarine include a change in destination into the early 1900s to include expanding markets in Asia, Central America, South America, and Africa.

These maps show the growth in exports of finished oleomargarine from the United States to other regions in the world from 1890 to 1910. The government distinguished these exports from raw oleo oil (see this page), which producers also shipped by the thousands of tons to foreign markets.

For margarine, the trade grew from five export ports in 1890 (Boston, New York, Philadelphia, Detroit, and New Orleans) to six in 1910 and from five main global regional destinations to eight. This was an increase from about 6 million pounds to 26 million pounds by the first decade of the twentieth century. Most of those foreign shipments first went to British colonial holdings in the West Indies, before being displaced in priority by shipments to Germany, Norway, and The Netherlands by the early twentieth century. As with shipments of raw oleo oil, notable trends include a change in destination into the early 1900s to include expanding markets in Asia, Central America, South America, and Africa.

Because trade records provide a wide range of quantities per year, for the sake of reader legibility the maps represent proportions. For example, an arrow five-hatch-marks wide is five orders of magnitude greater than an arrow with one hatch mark, while the width of the five-hatch arrow is five times the width of the one-hatch arrow. Readers can thus view the maps to gain a sense of growth in export markets, relative quantities to various parts of the world, and sense of scale in the global marketplace for supposed adulterants.

The maps derive from government trade statistics that listed departure ports (export locations) and final destinations (import locations), but not together. For instance, while we know manufacturers shipped x pounds of raw oleo oil from New York in 1890, we do not know where, specifically, that specific quantity ended up. Therefore, the maps show the commodities shipped from individual U.S. ports to meet in the Atlantic before dispersing to final destinations.

In general, government statistics used to construct theses maps documented foreign imports by country. Thus, in creating these maps the countries were aggregated into regions such as Northern Europe, Southern Europe, South America, Central America, Africa, and Asia. On the export side, various cities were aggregated into regions based on geographical proximity. The full data sets show specific nations.

The Washington Post publishes a short article with advice to use a low carb diet for obesity. "Simple Rules for a Successful Reduction Cure. IT ALL DEPENDS ON THE DIET. Food Containing Sugar and Starch Must Be put aside - The Quantity of Food Eaten Is Not of Importance if the material is of the proper kind— Ice cream, potatoes, and bread must be abolished."

Simple Rules for a Successful

Reduction Cure.

IT ALL DEPENDS ON THE DIET

Food Containing Sugar and Starch Must Be put aside - The Quantity of Food Eaten Is Not of Importance if the material is of the proper kind— Ice cream, potatoes, and bread must be abolished-- No water or Liquors at meals.

"This is the season of the year in which people who want to reduce their flesh would do best to begin," said a doctor who has made himself more famous in this particular field than any other American physician. "For one reason, there are fewer privations which the patient is compelled to endure now. Very few of the things that are delicacies at this time of the year are prohibited by a course of diet intended to reduce one's flesh. As a matter of fact, the forbidden articles are very few indeed, so surprisingly few that I always wondered why people look upon a course of banting as a hardship. Practically the only spring vegetables which should not be eaten are potatoes, beets, and peas, and no fruits are on the proscribed list.

"Patients who come to me receive one invariable prescriptlon. All fat comes from the same natural cause, and can be made to disappear in the same way.

I never can give any medicine beyond what is needed to put the patient in a state of good natural health. After I have accomplished that the reduction begins by following a method so publicly known that there is no reason why I should hesitate to reveal its use in my own case. It is wrong to say that only by a regimen of eating can a person's flesh be reduced. What is drunk has quite as much to do with the result.

"I begin by refusing to allow my patients to eat anything containing either starch or sugar. Bread must first of all be given up. There is enough fat-making material in one breakfast roll to counteract the effects of mineral water treatment taken for months. Bread must absolutely be kept off the bill of fare of any one who wants to get thin. Sometimes very dry toast may be eaten in very small quantities, but nowadays there are excellent substitutes for bread provided, and th ese are quite as toothsome if a person can only break himself for a while of the feeling that he must accompany every meal abundantly with rolls or crackers, as the case may be. The new breads made without any starch are, of course, admissible, because if they are what they pretend to be there can be no fattening substance in them.

"The bread out of the way, one great step has been accomplished. Sugar must follow, and the substitutes for that are so nearly the same in effect that nobody should mind taking saccarine in coffee, instead of several lumps of sugar. It is in puddings, pies, and other similar combinations of flour and sugar that these two substances are most missed, but all pastry, puddings, and desserts of any kind in which sugar is employed are forbidden. Sugar and starch must be left alone. And this includes all corn bread and similar bread foods made of flour, cornmeal, and similar substances.

All Liquors are Fattening.

"With practically no other foods forbidden, it is possible for a person to lose as much as five pounds a week by following the rules outlined. I have known thirty pounds to be lost in six weeks on this sort of a regimen. All meats, all kinds of fish, except salmon, and all vegetables, except beets, peas, lima beans, and potatoes, can be enjoyed. Liquor must in nearly every form be left entirely alone. Beer is, of course, so fattening hat no one with any idea of reducing his weight would ever touch it, and some other alcoholic drinks are very nearly as bad. Whisky is very fattening, and so is champagne. Such concoctions as cocktails, all kinds of punches, and other mixed drinks put on more fat that years of diet could take off. There is no hope in a reduction diet for the person who continues to take alcohol. Candles, of course, and sweets should never be touched, while ice cream and similar edibles are just as high up on the forbidden list.

"This practically completes the entire cure. One need only observe carefully these rules of diet to lose flesh certainly and quickly. More than that, such a selection of food would improve the patient's general health. Abstinence from starch and sugar is known to cure many bad cases of indigestion, and I don't believe there ever was a person following such a course that did not feel better for it. Wine in small quantities and usually white in color, and rather dry in quality, may be taken with a meal, but water."

Hubert Darrell was a man who understood thoroughly the principle of “doing in Rome as the Romans do,” and he had on many occasions, to my knowledge, in the past applied that principle so well that he was as safe as an Eskimo in his wanderings about the country; and really safer by far, for he had learned all the Eskimo had to teach him, and added to that knowledge the superiority of the white man's trained mind, and a natural energy and resourcefulness that are rare among men of any race.

Another piece of news which did not then bear the aspect of tragedy was that an Englishman, Hubert Darrell, had not reached Fort Macpherson after having visited the Baillie Islands in the fall of 1910. When Dr. Anderson repeated this piece of news to me we discussed it and agreed, as we still do, that Darrell was a man who would not have starved under ordinary circumstances, and we therefore felt sure that he had turned up alive and well somewhere or other unless sickness or accident had overtaken him. Darrell was a man who understood thoroughly the principle of “doing in Rome as the Romans do,” and he had on many occasions, to my knowledge, in the past applied that principle so well that he was as safe as an Eskimo in his wanderings about the country; and really safer by far, for he had learned all the Eskimo had to teach him, and added to that knowledge the superiority of the white man's trained mind, and a natural energy and resourcefulness that are rare among men of any race.

Although it was not until a year later that we became certain that the travels of Darrell over the northland of Canada had come to a tragic ending, I shall insert here a brief sketch of the man and his work. He was one that did not advertise, and although some of the most wonderful journeys ever performed in Arctic lands were done by him, the world would probably never have heard much of them even had he lived a longer time.

Darrell had come from England as a young man and owned a farm in Manitoba. I think it was the gold rush to the Yukon that first drew him thence to the North, although at that time he did not go much beyond Great Slave Lake, where he spent some time with the half caste and Indian hunters and travelers. He had already learned their ways when David T. Hanbury came there in 1901 and induced Darrell to join him on a trip eastward from Slave Lake to Chesterfield Inlet.

After spending the winter near Hudson Bay, a party consisting of Hanbury, Darrell, a third man named Sandy Ferguson, and about twenty Eskimo went inland, crossing north over Back's Great Fish River to the Arctic coast, following the coast west to the Coppermine River and ascending it to Dismal Lake, and there crossing over the divide which separates the waters of the Arctic Ocean from those of Great Bear Lake. Here the Eskimo turned back in August, and on their way home incidentally paid a visit to Captain Amundsen when he was wintering on King William Island, while the three white men proceeded by canoe across Great Bear Lake to the Mackenzie River. This was a journey of more than seven months in which the entire party had lived wholly on the country. It was Hanbury's last trip, but not so with Darrell.

I met Darrell first at Shingle Point on the Arctic coast, just west of the Mackenzie River, when I was spending my first winter among the Eskimo (1906–1907), and when he was on his way guiding a party of mounted policemen from Herschel Island to Fort Mcpherson. That was always his way. He was about as new to that country as the policemen were, but still he was a competent guide, for he never lost his head, and after all, in most places in the North it is not difficult to find your way if you keep your wits about you.

It was the winter before I saw him that he had made one of his most wonderful journeys. That winter Captain Amundsen with the Gjoa was wintering at King Point, halfway between the Mackenzie River and Herschel Island. In the fall of 1905 Captain Amund sen, as the guest of some whalers, traveled south in their company across the Endicott Mountains to the Yukon. The whalers and Amundsen had several sleds, and Eskimo to do the housework and camp making, and they traveled over a well- known road, where it is only a matter of three or four days from the time you leave the last Eskimo camp on the north side of the divide, where you can any time purchase deer meat, condensed milk, flour, or any such article you think you may need, up to the time you come to the first Indian camp on the south side of the divide, where you can supply yourself with dried fish, venison, and other articles of food. Amundsen has of course never said a word to indicate that he considers this Alaskan journey he made a difficult one, which as a matter of fact it is not; but the world at large insists upon considering it a marvelous feat, and the story, which the telegraphs and cables flashed all over the world, of the arduous road over which Amundsen had come to Eagle City, keeps echoing and reëchoing in the speech of men and in the pages of magazines.

That same winter Darrell also made a trip south from the Arctic Ocean to the Yukon. Instead of having whalemen for companions and Eskimo for guides, he went alone. Instead of having several teams and sledges, he had no dogs and only a small hand sledge which he pulled behind him; and on that sledge he carried sixty pounds of mail. He made his way from Fort Macpherson over the mountains by a more difficult road than that followed by Amundsen's party. Although he traveled alone he had no adventures and no mishaps (adventures and mishaps seldom happen to a competent man), and when he arrived on the Yukon the telegraph despatches recorded the simple fact that mail had arrived from the imprisoned whalers in the Beaufort Sea, and not a word of who had brought it or how it had been brought.

On the Yukon Amundsen happened to meet Darrell. He recognized the feat for what it was — one of the most remarkable things ever done in Arctic lands. “ With a crew of men like that,” Amundsen says, “ I could go to the moon.” Although he no doubt never expected to see him again, Captain Amundsen invited Darrell to visit him on the Gjoa at Shingle Point. Darrell does not seem to have agreed to this at once, and Amundsen returned with his party north to the coast, leaving Darrell behind on the Yukon. But one day towards early spring Darrell turned up at Amundsen's camp at King Point. He had come alone again over the mountains by a new route, and without adventure, as always.

From the time I saw him guiding a party of mounted police in November, 1906, I did not see Darrell again until the summer of 1908, when I met him at Arctic Red River, the most northerly Hudson's Bay post on the Mackenzie River proper. In the meantime he had been making his quiet journeys alone, here and there through the north, and that fall I believe he crossed the mountains again to the Yukon. I do not know what his movements were from that on until the fall of 1910, when he appeared at the Eskimo village at the Baillie Islands, without dogs as usual, and dragging his sled behind him. The schooner Rosie H. was wintering there at the time, but Captain Wolki was away and the ship was under the command of her first officer, Harry Slate.

To travel alone and without dogs is an unheard of thing even among the Eskimo, and both they and Mr. Slate tried first to get Darrell to stop over and next offered to give him some dogs to haul his sled, but both without avail. He was used to traveling that way, he said, and it would be too much bother to hitch up the dogs in the morning. He told them further, truly, that nothing would go wrong so long as no accident happened, and that to have dogs with him if an accident did happen would be of no particular use.

Darrell had been with a canoe up Anderson River the previous summer and had left his camp near the mouth of the river at the foot of Liverpool Bay. In order to return there he started southwest from the Baillie Islands, and a few days later he met some Eskimo by whom he sent a letter to Mr. Slate. At first Darrell had intended to come and visit me (for our base at Langton Bay was only ninety miles east of the Baillie Islands), but Slate had told him that I would not be at home, and only Ilavinirk's family were keeping the camp for me. He had therefore decided not to come. The letter he wrote Mr. Slate, which contains some messages to me, is the last positive thing we know of Darrell. In it he says, as he had already told Slate, that he intended to go the three hundred miles or so to Fort Macpherson and thence across the mountains to Dawson, and intended to return the next year. Eskimo information makes it clear that he left his camp in Liverpool Bay, but in what direction he went we do not know. Personally, in making such a journey, I should have traveled along the coast; but Darrell was used to the woodlands, and certainly the woods are an advantage in a way, although the snow is soft among the trees. It may be that he tried to go straight overland through the forested area from Liverpool Bay to Fort Macpherson. It is also possible that he may at the last moment, because of approaching sickness or for some other reason,, have taken to the ice of the Anderson River with the idea of reaching a camp of the Fort Good Hope Indians, who may be expected at one place or another after you get a hundred miles up the Anderson.

The only thing discovered since Darrell was last seen that may possibly be a clew, is that some Eskimo told me at the Baillie Islands in March, 1912, that the previous summer they had been in a boat up the Anderson River and had seen a blazed tree with some writing upon it. As a good many of the Fort Good Hope Indians can read and write, the chances are that this is some of their scribbling. Nevertheless I advised the Eskimo if they went up to the place again to cut down the tree and bring the piece containing the writing down to Captain Wolki at the Baillie Islands. It is not likely we shall ever know what the ultimate end of Darrell was; but whatever it was, those who knew him feel sure that he met it bravely and without heroics.

(Hubert Darrell's writings are in Oxford - https://archiveshub.jisc.ac.uk/search/archives/c5cc2dca-ab2c-3087-aead-cce2545ca9b7?terms=%22Darrell%20Hubert%201875-1910%22)

Opie realizes diabetes occurs due to a failure in the islets of Langerhans in the pancreas.

American pathologist Eugene Opie of John Hopkins University in Baltimore establishes a connection between the failure of the islets of Langerhans in the pancreas and the occurrence of diabetes.

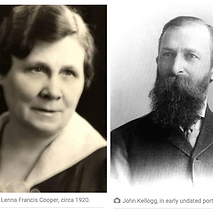

"In 1901, Lenna graduated in nursing from the Battle Creek Sanitarium (a Seventh-day Adventist health institution) in Battle Creek, Michigan. It was there that she became a protégé of the famed vegetarian physician, Dr. John Harvey Kellogg, superintendent, and medical director of the sanitarium."

In 1901, Lenna graduated in nursing from the Battle Creek Sanitarium (a Seventh-day Adventist health institution) in Battle Creek, Michigan. It was there that she became a protégé of the famed vegetarian physician, Dr. John Harvey Kellogg, superintendent, and medical director of the sanitarium. During the early part of the twentieth century, the Battle Creek Sanitarium became world-famous as a leading medical center, spa-like wellness institute, and grand hotel that attracted thousands of patients actively pursuing health and well-being. The sanitarium served only vegetarian meals to its patients and visitors. People of all social classes from around the world flocked to the Sanitarium to personally experience its unique vegetarian diet and wellness program, which Dr. Kellogg called “biologic living”. The Sanitarium’s notable guests included Mary Todd Lincoln, Amelia Earhart, Booker T. Washington, Johnny Weissmuller, Henry Ford, Thomas Edison, John D. Rockefeller Jr., George Bernard Shaw, and J.C. Penney. Dr. Kellogg and his team of dietitians even worked with presidents such as William Howard Taft, Warren G. Harding, Herbert Hoover, and Franklin Delano Roosevelt.

Under the tutelage and inspiration of Dr. Kellogg and his wife, Ella Eaton Kellogg, Lenna first developed her love for the study of foods and their scientific preparation. Dr. Kellogg encouraged Lenna to go to the Drexel Institute in Philadelphia to study foods and food chemistry where she excelled in her studies. She later received her bachelor’s (1916) and master’s (1927) degrees from Columbia University.

Dr Osler reduces starches and sweets and sometimes fats to help with obesity

"We are often consulted by persons in whose family obesity prevails to give rules for the prevention of the condition in children or in women approaching the climacteric. In the case of children very much may be done by regulating the diet, reducing the starches and fats in the food, not allowing the children to eat sweets, and encouraging systematic exercises. In the case of women who tend to grow stout after child-bearing or at the climeratic, in addition to systematic exercises, they should be told to avoid taking too much food, and particularly reduce the starches and sugars. There are a number of methods or systems in vogue at present. In the celebrated one of Banting, the carbohydrates and fats were excluded and the amount of fat was greatly reduced.”

Dr. J. Lyman Bulkley never found a single true case of carcinosis while in Alaska.

Dr. J. Lyman Bulkley was born at Sandy Creek, New York, in 1879. He studied medicine from 1896 to 1900 and was graduated with the latter year's class from the medical school of Syracuse University. That year, or the next, he went to Alaska, where, after vicissitudes, he settled down to the practice of medicine at Valdez for some ten years, his last known address there being on McKinley Street. In 1927 he was associate editor of the New York City journal Cancer, under chief editor Dr. L. Duncan Bulkley. To the July issue of 1927 Dr. J. Lyman Bulkley contributed an article, “Cancer among Primitive Tribes,” in which he wrote:

“The observations, which the author of this article has used, principally ... are the result of the experiences of others ... His own personal observations on the subject were gathered during a sojourn of about twelve years among several of the different tribes of Alaskan natives, during which time he never discovered among them a single true case of carcinosis ...

“In the nearly twelve years which the writer of this article spent in Alaska, during which he came into contact with many of the different tribes of the natives living there (although not all), he never found a true case of cancer among the full-bloods and but very few among those of mixed blood. The food of these people consists almost exclusively of fish and some shell fish, with cereals, berries and some vegetables ...

“... the writer feels that the conclusion can be safely drawn that to civilization and all its influences may be attributed in a very large measure ... the increase in frequency of malignancy among primitive races.”

In a few cases of disease such as flatulent dyspepsia, chronic gastritis, diabetes, obesity and chronic dysentery, an almost exclusive meat diet, with only a little dry bread, has been found beneficial. Fat and lean meat of animals taken together contains all the fourteen elements of which the human body is composed. A man could, therefore, live on an exclusive meat diet.

THE FOOD VALUE OF MEATS.

It is not the purpose of this article to discuss the pros and cons of vegetarianism. Man's adaptability to conditions is great, and while men may live and apparently thrive for a time upon a one-sided diet, a generous mixture of animal and vegetable food is best calculated to enable a man to meet the exigencies of our civilization and the nervous strain of our large cities.

In this country our prosperity, the excellence of our meat supply, and the habit which most Americans have formed of eating a good deal of meat, makes it more important to dwell upon

the ill effects of eating too much meat, rather than upon the necessity of eating some.

Fat and lean meat of animals taken together contains all the fourteen elements of which the human body is composed, but not in the same proportion. A man could, therefore, live on an exclusive meat diet, though owing to the great concentration of such food, it would not be advisable for him to do so. The human body requires four times as much heat-producing as muscle-making food and as the main function of meat is to repair old tissue and form new, he would need to eat great quantities — about six and a half pounds daily — to furnish heat which could be much more advantageously derived from some form of starchy or saccharine food. These, too, would furnish the bulk needed to keep the bowels in proper condition, and would lessen the waste products to be elIminated by the kidneys.

In a few cases of disease such as flatulent dyspepsia, chronic gastritis, diabetes, obesity and chronic dysentery, an almost exclusive meat diet, with only a little dry bread, has been found beneficial.

While for well persons, the stimulating qualities of meat eaten in moderation are desirable, the deleterious matter of which the system must rid itself when too large an amount is indulged in, thwarts the very purpose for which it is taken and renders the brain dull and the whole person lumpish.

To lay down a general rule for the amount of meat to be consumed by a person in a day would, however, be impossible since the state of health, the age, occupation and climate all modify very materially the proper daily ration.

It is thought, and not without foundation, that meat makes the blood rich by increasing the number of red corpuscles in it. It is, therefore, often prescribed by physicians for anemic persons and consumptives. Raw meat, which is sometimes given in such cases, has no advantage over lightly cooked meat, in fact the latter is much more wholesome. Meat should be entirely prohibited in acute or chronic Bright's Disease, gout and rheumatism. It is well known that meat is conducive to tissue building and for this reason children over eighteen months old should have meat at least once a day and better twice a day. Growing boys need much meat and should be allowed a larger amount at a meal than their elders ; but no person in health should take meat more than twice a day. A small boy may, with propriety, eat from five to six ounces at a meal. Boys of ten years from seven to eight ounces, and large boys from seven to twelve ounces. Men and women over fifty years of age ought to eat sparingly, especially of meat, as the waste products of meat are the urates, phosphates, sulfates and urea which must be excreted by the kidneys and hence tax these organs, besides making all the fluids of the body acid, causing rheumatism and gout.

Persons eating much meat should have abundant out-door exercise, as nearly every particle of meat must be burned up in the body and large quantities of oxygen are needed for this. Sedentary men should, therefore, not eat heavy meat meals especially during business hours.

Fat furnishes heat, but in so concentrated a form that a certain amount of fat produces two and a half times as much heat as an equal amount of starch or sugar. On this account pork with other food forms a suitable diet for cold weather, since the fat and the lean of an ordinary portion contain five parts of heat-producing material to one part of muscle-making substance. Veal is a good meat to serve in warm weather, as even the lean portions of it contain but little fat; but veal is only suited to persons with absolutely normal digestion, since, being an immature meat it is less easily digested and assimilated than beef or mutton.

Meat has been supposed by some to tax the digestive organs proper, more than other food; but, while it remains in the stomach from an hour to two hours longer than vegetables, the digestion of the lean part is practically accomplished in the stomach and little work thus devolves upon the intestinal ferments, so that it does not require more energy, on the whole, to dispose of meats than to dispose of foods such as starches and sugars which are hurried through the stomach, but must undergo a long process of intestinal digestion.

The products of the digestion of meats, moreover, enter more quickly into the blood, and its sustaining effect is more quickly felt than when another kind of food is taken. Any sudden exertion is known to be more easily withstood by a man accustomed to a meat diet than by another.

The thing which does tax the digestive organs is to oblige them to supply all the needs of the body from food of one kind, be that either meat taken entirely, or vegetables and starches eaten exclusively. Meat, vegetables and bread may be eaten together ; or milk or cheese may be substituted for meat, and eaten with vegetables and bread. Either of these combinations forms a good diet for well persons.

Helen G. Sheldon

Labrador Eskimos' muscles are rested by a shorter period of sleep than is customary among civilized peoples. Men and women alike show the power of withstanding fatigue.

This “inevitable doom” must have seemed even blacker to the Moravian medical missionaries who had dreamed it could be staved off indefinitely by avoiding the Europeanization of the food — by inducing healthy people to remain healthy through continuing to eat the raw foods which they loved and which they could secure in ample quantity from their own land and waters.

Ruefully Superintendent Peacock admits that the best they were able to do was to slow up Europeanization by a few generations. Among the first subversive influences, tending toward eventual dependence on the white man, was the fact that the Eskimos contracted first the tobacco habit and then the tea habit. Thereafter followed gradually the use of bread, salt, and sugar; then came increased cooking and the use of hot drinks. Still it was possible as late as the period 1902-13 for Dr. Hutton to conclude from his own observation that “cookery holds a very secondary place in the preparation of food.”

While he makes this observation on cooking as part of a suggested explanation as to why he could find no hearsay or other sign of cancer among the Labrador Eskimos, Dr. Hutton also makes, elsewhere, the general observations on the health of the Labrador Eskimo that “... his muscles are rested by a shorter period of sleep than is customary among civilized peoples. Men and women alike show the power of withstanding fatigue.” So long as their diet continued to consist exclusively of their own fresh foods, hardly cooked or raw, their robust health broke down only when they were exposed to European diseases against which they had no inherited immunity, such as the deadly measles and the almost equally deadly tuberculosis. But on the Europeanized diet they became prey to a swarm of other new diseases.

Gary Taubes wrote in his new book The Case For Keto a paragraph that I want to dedicate this database towards:

"I did this obsessive research because I wanted to know what was reliable knowledge about the nature of a healthy diet. Borrowing from the philosopher of science Robert Merton, I wanted to know if what we thought we knew was really so. I applied a historical perspective to this controversy because I believe that understanding that context is essential for evaluating and understanding the competing arguments and beliefs. Doesn’t the concept of “knowing what you’re talking about” literally require, after all, that you know the history of what you believe, of your assumptions, and of the competing belief systems and so the evidence on which they’re based?

This is how the Nobel laureate chemist Hans Krebs phrased this thought in a biography he wrote of his mentor, also a Nobel laureate, Otto Warburg: “True, students sometimes comment that because of the enormous amount of current knowledge they have to absorb, they have no time to read about the history of their field. But a knowledge of the historical development of a subject is often essential for a full understanding of its present-day situation.” (Krebs and Schmid 1981.)