Book

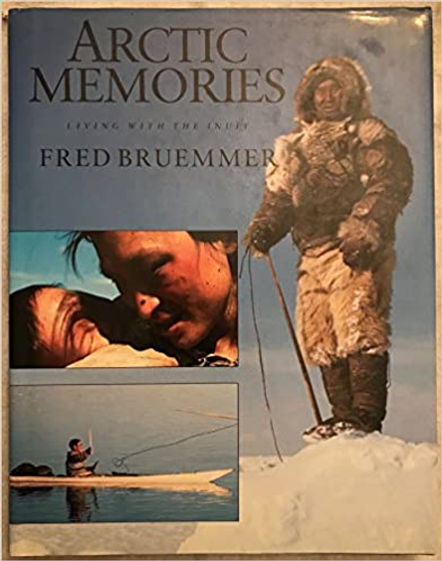

Arctic Memories: Living with the Inuit

Publish date:

March 1, 1994

ARCTIC MEMORIES, is about Fred Bruemmer's experience with The Inuit. He shared their food, their homes, their travel their hardships and their happiness. It is a celebration and praise of people who understand the indivisibility of life.

Excellent book with awesome pictures that has a few anecdotes about all meat diets. I really enjoyed it. I found a physical copy in a thrift book store.

Authors

Image | Author | Author Website | Twitter | Author Location |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Fred Bruemmer | Deceased |

Topics

History Entries - 10 per page

Monday, June 2, 1975

Fred Bruemmer

Arctic Memories - Fishing, Clamming, and Crabbing

Bruemmer discusses other important sources of animal foods for the Inuit, including clams, some even pulled from the stomachs of walruses, fish caught through holes or in nets made of whale baleen, crabs, and even a raw seal feast.

FISHING, CLAMMING, CRABBING

It is almost as though the Inuit in former days were following God's injunction to Noah that "every moving thing that liveth shall be meat for you," and caught, killed, and ate anything, from 2-ounce (56-g) lemmings to 60-ton (54-tonne) bowhead whales.

By far the most important animals to them, however, were seals and caribou, the sine qua non of their life in the Arctic. Had God created the world with only these two animals, the Inuit would have been content, for seals and caribou supplied them with most of their food and clothing.

Some groups specialized: the people of Little Diomede Island in Bering Strait are primarily walrus hunters. The Inuit of the Mackenzie Delta region hunted white whales, and still do. The inland Inuit had no seals; they lived mainly on caribou and fish, and obtained durable sealskins (for boot soles) and seal oil (for their stone lamps) in trade from coastal people.

There were no caribou in a few Arctic regions. They died out on the Belcher Islands in Hudson Bay in the 1880s when an abnormal winter rain was followed by heavy frost and the islands were covered with a hard, glittering carapace of ice. The caribou could not dig through it for food, and all starved to death. Deprived of caribou pelts for winter clothing, the ingenious Inuit made them from cider-duck skins. A mirvin, an eider-duck parka, was as warm as a caribou parka, but not as lasting.

In addition to vital seal and caribou, nearly all Inuit caught fish, from small, bony sculpins to huge Greenland sharks, whose toxic meat could be eaten only by people who knew how to prepare it. The Inuit had nets: in the Bering Sea region they used large nets of seal or walrus thong to capture seals, and even whales. In Greenland, the English explorer John Davis saw in 1586 nets made of baleen: "They (the Inuit] make nets to take their fish of the finne of the whale." (Siberia's Chukchi, close neighbors of the Inuit, wove their nets of nettle fibers.) The most common way, though, to capture fish was with hook and line, or with leisters.

The most important, most delicious fish was char, once infinitely numerous in lakes and rivers and the sea. Unlike its close cousin, the salmon, the char does not jump. Taking advantage of this, Inuit built sapotit across rivers, often in rocky rapids, with an entrance sluice leading to a central, rock-surrounded basin. Once the basin was swarming with ascending fish, the Inuit closed the low stone weir, jumped into the icy water, and speared the char with three- pronged leisters. It was numbingly cold, but wildly exciting: the women screaming on shore, the children jumping on the rocks, and then great feasts of fish, and rocks covered with blood-red split char, drying for the coming winter.

Octave Sivanertok of Repulse Bay, on the northwest coast of Hudson Bay, took me along in spring to fish for char and lake trout. He drove his powerful snowmobile with speed and consummate skill. The long sled, pulled by ropes, rattled and hammered over rock-hard snow and ice ridges, and often slewed wildly. I got a merciless pounding and had to hang on like a limpet to avoid being tossed off when the sled caromed off ice blocks. With the snowmobile, Arctic travel gained in speed but lost most of its romance and comfort. Traveling by dog team, leisurely and silent, was usually a pleasure. One was aware of land and frozen sea, and felt as one with it. But it was slow. Octave covered in hours what would have taken days with a dog team.

We stopped for the night near a frozen lake. Octave built an igloo, wind-proof and much warmer than a tent. He chiseled a hole through the 6-foot (2-m)-thick ice of the lake, built a windbreak of snow blocks, and jigged for lake trout. I went for a long walk to relax my battered bottom. When I returned, the last rays of the setting sun slanted across land and lake and flecked the snow with nacre and gold. Octave, endlessly patient, still jigged for trout. A row of speckled, bronze-glistening fish lay near him.

Next day we crossed Tesserssuaq, the big lake, and finally came to Sapotit Lake, really a series of lakes connected by shallow, fast- flowing rivers. Dark water welled up and poured in milky-turquoise streamers across the ice. Here, in summers long ago, men caught char at sapotit. Many of the ancient stone weirs still existed, but were breached to let the migrating fish pass. Now many Inuit had come, like us, from Repulse Bay to spear fish with leisters. They kneeled at the edge of the ice, jigged metal lures with metronome regularity (in former days the lures were of carved ivory or polished bone), held leisters poised, and peered intently into the crystal-clear water for the golden flash of trout or the silver and rose of char. A lightning thrust, and the fish, held firmly by the leister prongs, was pulled onto the ice. Some leisters were still made of musk-ox horn, the best traditional material, strong and flexible. New leister tines were carved from the strong, thick plastic used for the counters of butcher shops. Sapotit and leisters are among mankind's oldest inventions. Magdalenian hunters used them 30,000 years ago during the final Paleolithic culture in western Europe.

Clams, where available, are a favorite food for Inuit. Some come already collected and even a bit predigested. At Little Diomede Island in Bering Strait, walrus hunters took 50 pounds (22.5 kg) and more of recently shucked clams from the stomach of each walrus they killed. Masses of these clams were eaten fresh, raw or cooked, and more were slipped onto strings and air-dried for future use. In 1975, when I first lived on Little Diomede, I tried to improve on this by making clam chowder and invited Inuit friends to my shack for supper. But the clams, soaked in walrus gastric juices, curdled the milk, and the chowder, like nearly all my cooking, was a disaster. When I returned fifteen years later to live again on Little Diomede, it was still remembered. "Have you come back to make more chowder?" someone asked.

At Aberdeen Bay on the north shore of Hudson Strait, which the Inuit call Taksertoot, the place of fogs, we had to dig our own clams. Inuit from the settlements of Lake Harbour and Cape Dorset also gather at this remote bay to quarry with pickaxes, chisels, sledgehammers, and crowbars the distinctive jade-green soapstone for which their superb carvings are famous.

Hunting in Inuit society is man's work. Both men and women fish. But clam digging, berry picking, and egg collecting are usually family affairs, and Inuit often make it into a joyous outing. Matthew Kellypallik of Cape Dorset saw me on the beach and called: "You want to come along?" (I had dropped broad hints in camp that I wanted to go on a clamming trip), and we were off, a large canoe full of happy people, two pet dogs, and lots of zinc and plastic pails. We drove to a far bay and, as the tide (here more than 30 feet [9 m] high) receded, walked out onto the great mud flats and dug for clams with spoons, forks, knives, or sticks, most soon bent or broken. Some clams were huge - hand-long and perhaps forty or fifty years old. There are few walruses on this coast, and humans rarely visit; most clams can grow and age in peace. An earnest little boy, shy but keen to teach, took me in tow and showed me the telltale bubbles of retracting siphons and how to dig out the clams. Before the tide returned our pails were full, and a huge pot of clams was boiling on the pressure stove. We returned late in the evening, mud-smeared, full of clams and pleasantly tired. On the broad camping beach, a dozen tents, lit by pressure lamps, glowed yellow in the deep-blue dusk.

We passed an elegant cabin cruiser. Its owner, a world-famous Inuk carver, leaned over the railing and recognized me. ' "Killiktee [an old Inuk at whose camp I had lived for several months] says Hallo!' " he called. "He says you eat our food just like an Inuk. Come eat with us tomorrow. We shot some seals. We ate in the main cabin of the cruiser, paneled in warm mahogany, the brass fittings shining, the deep-pile carpet burgundy red. The Inuit spread cut cardboard boxes on the carpet and upon them laid the seal, our supper. The host slit it open from throat to hind flippers, and we ate it, kneeling around the carcass and observing the ancient, traditional meat division of this region: the women ate the heart, the men the liver, the women took ribs and meat from the ventral region, men vertebrae and the dorsal meat, eating the lean, dark, blood-rich meat together with snippets of blubber. We washed our hands, drank lots of very sweet tea, and talked of hunting and carving. Big chunks of soapstone, my host explained, are called "bank stones.' "Why?" I asked. He laughed: "Because only banks can afford to pay for the large carvings made from them."

In a few places in Alaska, Inuit not only catch a lot of fish, but also capture crabs by a simple yet ingenious method. At Little Diomede Island in late winter and spring, women, children, and some men spend patient hours "crabbing" at holes chiseled through the ice, catching crabs that measure, including spindly legs, about 2 feet (60 cm) in diameter (northern cousins of the famous king crabs). A stone sinker and two chunks of fish as bait are lowered on a thin line to the sea bottom. A feeding crab, loath to lose food, hangs on as it is pulled gently upward. Only when it is nearly at the surface does the crab seem nervous and loosen its grip, but that hesitation is fatal: the fisherman gaffs it or grabs it and throws it on the ice. The most patient crabbers caught twenty or thirty crabs in a day, enough for several delicious meals, and carried them home in burlap bags.

Sculpins, say the Little Diomeders, are attracted by anything red. In former days, the bait was the bright orange-red skin flap near the base of the bill of crested auklets, small seabirds which the islanders scooped out of the air with long-handled nets. Now they use bits of red plastic as sculpin bait, or chips of ivory tinted red with Mercurochrome.

Some fish catches are wholly fortuitous. Masautsiaq Eipe, Sofie Arnapalãq, their grandson, and I were on our way from Qaanaaq, main village of Greenland's Polar Inuit, to the floe edge 60 miles (96 km) away to hunt seals and whales. A lead, sealed by new- formed ice and covered with snow, stopped us. Masautsiaq tested the ice with a steel-tipped pole; when the ice broke, he called out in happy surprise. The lead was filled with dead Greenland halibut, flat, flounder-like, clay-colored fish, 2 feet (60 cm) long and delicious when fresh. The Inuit used to catch them with long lines made of bowhead-whale baleen and catch them now with nylon lines armed with many hooks. Most fish in the lead had been swept there by currents and were far from fresh. The best ones were for us, the rest were excellent dog food. Huskies are not fussy. Masautsiaq, prepared for most eventualities, carried several large sealskins and a huge sheet of plastic on his sled. With these he now fashioned a boat-shaped container on the sled, we filled it with fish, covered the slippery load - perhaps 600 pounds (270 kg) - with more sealskins, piled our bed robes and possessions on top, lashed all securely with thong, and, perched high on the sled and now amply provided with food for us and the dogs, traveled on to the floe edge.

Sunday, April 15, 1990

Fred Bruemmer

Arctic Memories - Return to Diomede

"Long ago, when I was young, said Albert Iyahuk, "people were never sick." Now cancer and heart disease were common; one of the causes may be a partial change to Western food. Recent studies by scientists have shown "that the incidence of cancer [among Inuit] has increased significantly following westernization."

I flew to Anchorage, Alaska, in the spring of 1990 and the news was bad. Hunting for ivory had fallen into ill repute. To save Africa's elephants a world-wide ban on ivory trade was now in effect. There had been reports in magazines and in Alaskas press of Inuit "headhunting, of killing walruses only for their tusks, leaving the headless carcasses upon the ice. The more lurid reports spoke of "chainsaw gangs" that lopped off walrus heads. The Diomeders, I guessed, would be very touchy. A Japanese TV crew, I was told, had offered the Diomeders big money to film the walrus hunt and had been curtly advised that they and their money were not wanted. "I wouldn't be surprised," a biologist friend in Anchorage told me, "if they put you back on the helicopter and tell you to fly off."

That was another change: a heliport at Diomede and weekly helicopter service from Nome. It all looked so familiar: the fields of ice in Bering Strait; the soaring cliffs of Diomede; the weather-gray houses glued to the mountainside; the umiaks on their racks; the great rust-red tanks for oil and gas. I stared down and worried about my welcome. The helicopter landed on a new metal pad on the beach. There was the familiar smell of sea and wrack and walrus oil. And there stood Tom Menadelook and Mary. He recognized me instantly and was as brief and decisive as ever. "Good to see you back," he said. "Mary and I are going to Portland [Oregon] for Etta's graduation. You can stay at our house." Junior," he called, and from the crowd around the helicopter came a heavyset, sturdy young man: Tom, Jr., now twenty-six, father of three lovely children, a fine hunter, and the village policeman. "This is Fred," his father said. "He'll stay at our place. Get him the keys. And he'll go out again with our boat." All my worries vanished.

Young men carried the bags up to "my" house. I followed slowly, up the steep, familiar cobbled path. Annie Iyahuk sat on the steps of her house. "Come in," she said. "Albert will be glad to see you." Albert, with whom long ago I had collected greens on the slopes of Diomede, now in his seventies, was thin and frail but still an excellent carver. He grasped my hand in both of his. "Ah," he said. "You came back to us." I was given tea and bread, and hard-boiled eggs with seal oil. After fifteen years, it was like coming home.

There had been many changes in these years: a large new school had been built, a new store, some new houses, a "washateria" owned, like the store, by the islanders and paid for, in large part, with money made from ivory carving. It was kept spotlessly clean and for three dollars one could shower, wash a load of clothing, and dry it. The washateria brought in $100,000 in its first year of operation.

There was one drastic change: Diomede was dry. All alcohol was forbidden. The planes with booze, the wild parties, the fights, the smashed windows, the drunken threats, the bilious hangovers were now only memories of a violent past. "It sure is quiet, kidded George Milligrock, once one of the wild young men of Diomede and now approaching portly middle age. "Yes," he agreed with a touch of regret, "we're getting to be quite civilized." Young Inuit who had tried city life in Nome, Anchorage, or Seattle and were nearly crushed by drink and other problems, had returned to Diomede, to their roots, to an older, simpler way of life. The population of Ignaluk, after shrinking for many years to a low of 84 in 1970, had increased to 121 in 1975, and to 171 in 1990.

Life on Diomede was peaceful, pleasant, quiet. It certainly was a nicer, gentler place than on my first visit - and yet, some of the panache, the verve, that devil-may-care daring was gone, and at times I felt a certain perverse nostalgia for the wildness of the bad old days.

"Civilization" also seemed to have exacted a bitter price. Once Diomeders had been famous for their daring and their vigorous health. The Smithsonian Institution anthropologist Ales Hrdlicka visited Little Diomede in 1926. "The natives look sturdy, " he noted. "None other could survive here." Shortly after I arrived, I met John Iyapana who, on my previous visit, had taken me by umiak back to the mainland. I remembered him as a weather-beaten, bluff bear of a man, violent when drunk, affable when sober, with an immense fund of stories about Diomede. Now he was a broken hulk, wan and weak. He pulled a notebook from his pocket and wrote: "Welcome back, Fred! Cancer had destroyed his throat and vocal cords; he could no longer speak. He would never tell stories again.

"Long ago, when I was young, said Albert Iyahuk, "people were never sick." Now cancer and heart disease were common; one of the causes may be a partial change to Western food. Recent studies by scientists from the Emory University Medical School have shown "that the incidence of cancer [among Inuit] has increased significantly following westernization."