Recent History

October 5, 1949

Helge Ingstad

Nunamuit: Among Alaska's Inland Eskimos

The Nunamiuts thrive on this almost exclusively meat diet; scurvy or other diseases due to shortages of vitamins do not exist. They are, in fact, thoroughly healthy and full of vitality. They live to be quite old. I lived only on meat for nearly five years.

I am writing at the beginning of October. Now the women are going for trips up the hillsides in small parties and enjoying themselves picking berries and gossiping. They find a fair number of cranberries and whortleberries, but no great quantities. Cloudberries are scarce in the Anaktuvak Pass; there are said to be more farther north, on the tundra.

The berries are stored raw, sometimes in a washed-out caribou's stomach, and mixed with melted fat or lard. This dish is called asiun and is considered a special delicacy.

They also dig up some roots. The most sought after are maso, qunguliq (mountain sorrel), and airaq. What is collected is consumed before winter sets in. No new green food is to be had till May; then roots and the fresh shoots and inner bark of the willow are eaten. Thus, for about seven months the Nunamiuts live on an exclusively meat diet, and for the rest of the year their vegetable nourishment is very scanty.

The caribou is dealt with traditionally. Every single part of the animal is eaten except the bones and hooves. The coarse meat, which in civilization is used for joints and steaks, is the least popular. In autumn and spring it is used to a certain extent for dried meat; otherwise it is given to the dogs. The heart, liver, kidneys, stomach and its contents, small intestines with contents (if they are fat), the fat round the bowels, marrow fat from the back, the meat which is near the legs, etc., are eatn. Both adults and children are very fond of the large white tendons on the caribou's legbones; they maintain that food of this kind gives one good digestion. The head is regarded as a special delicacy; the meat, the fat behind the eyes, nerves, muzzle, palate, etc., are eaten. Finally, there are the spring delicacies--the soft, newly grown horns and the large yellowish-white grubs on the inside of the hide(those of the gadfly) and in the nostrils. The grubs are eaten alive.

The meat is often cooked, but to a large extent it is also eaten raw. The children often sit on a freshly killed caribou, cut off pieces of meat, and make a good meal. It is also common practice to serve a dish of large bones to which the innermost raw meat adheres. Dried meat and fat are always eaten raw.

The Nunamiuts' cuisine also offers several choice delicacies. First and foremost is akutaq. To prepare this dish, fat and marrow are melted in a cooking-pot, which must not get t oo warm, meat cut fine is dropped in on the top, and then the woman uses her fist and arm as a ladle to stir it about. The result is strong and tastes very good. Akutuq has since ancient times been used on journeys as an easily made and nourishing food and is fairly often mentioned in the old legends.

Then there is qaqisalik, caribou's brains stirred up with melted fat. A favourite dish is nirupkaq, a caribou's stomach with its contents which is left in the animal for a night and then has melted fat added to it. It has a sweetish taste which reminds one of apples. Finally, there is knuckle fat. The knuckles are crushed with a stone hammer to which a willow handle has been lashed. Then the mass is boiled til the fat flies up. The Eskimos attach great importance to the boiling's not being too hard; delicate taste. Sometimes it is mixed with blood, and then becomes a special dish called urjutilik.

The Nunamiuts like chewing boiled resin and a kind of white clay which is found in certain rivers. Salt is hardly used at all. If an Eskimo family has acquired a little, it is used very occasionally, with roast meat. The small amount of sugar, flour, etc., which is flown in in autumn is of little significance and has, generally speaking, disappeared before the winter comes. Some Eskimos do not like sugar.

For a while coffee or tea is drunk, but these are quickly finished. Then the Eskimos fall back on their old drink, the gravy of the cooked meat.

The Nunamiuts thrive on this almost exclusively meat diet; scurvy or other diseases due to shortages of vitamins do not exist. They are, in fact, thoroughly healthy and full of vitality, so long as sicknesses are not imported by aircraft. They live to be quite old, and it is remarkable how young and active men and women remain at a considerable age. Hunters of fifty have hardly a trace of grey hair, and no one is bald. All have shining white teeth with not a single cavity. The mothers nurse their children for two or three years.

It is an interesting question whether cancer occurs among the Nunamiuts or among primitive peoples at all. On this point I dare not as a layman express an opinion, but I heard little of stomach troubles. During my stay among the Apache Indians in Arizona (1936) a doctor in the reservation told me that cancer had not been observed among the people. According to a Danish doctor, Dr. Aage Gilberg (Eskimo Doctor, George Allen and Unwin, London, 1948), cancer is never sene among the Thule Eskimos in northwestern Greenland. The matter deserves more detailed investigation; it may possibbly give certain results of assistance to cancer research.

The Indian caribou hunters I once lived with in Arctic Canada had a similar meat diet and good health. As for myself, my fare was the same as the Indians' and the Eskimos'--practically speaking, I lived only on meat for nearly five years. I felt well and in good spirits, provided I got enough fat. My digestion was good and my teeth in an excellent state. After my stay with the Nunamiuts I had not a single hole in my teeth and no tartar.

No doubt the hunters of the Ice Age, in Norway and elsewhere, lived in a similar way many thousand years ago. We are probably in the presence of what is most ancient among the traditions of primitive peoples. Taught by experience, they have arrived at a manner of living which, despite its onesideness, fully satisifies the body's requirements. The principle is to transfer almost everything that is found in the caribou to the human organism.

It is interesting to note that the stomach and liver of animals are regular features in the diet of primitive peoples, whereas modern science has only quite recently established that these contain elements of special value to human beings. The remedy for the previously deadly pernicious anemia is obtained from them. The contents of the caribou's stomach and the newly grown horns merit a closer examination by modern methods. It is a question, for example, whether the cellulose of the moss decomposed in the caribou's stomach and thereby becomes available to the human organism. With regard to the horns, it is of interest that certain deer's horns from northeastern Manchuria have from time immemorial been a regular article of commerce in China, where they have been used as a cure for impaired virility.

Typed up by Travis Statham from physical book. This is the best quote in the entire book.

Note: Helge Ingstad lived to be 101 (1899-2001).

August 1, 1966

Fred Bruemmer

Arctic Memories

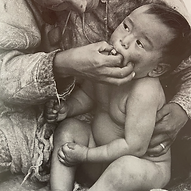

Elizabeth Arnajarnek feeds a pre-chewed morsel of caribou meat to her baby at a camp on the Barren Grounds in 1966. The Inuit gather thousands of duck eggs and eat them raw or hard-boiled. They store them for the winter.

Noises and voices drifted through the fog; the creak and groan of tide-moved ice; the honking of Canada geese; the plaintive calling of red-throated loons; the lilting song of snow buntings; the haunting, mellow woodwind crooning of courting eider drakes.

Early next morning, the fog lifted. We climbed a hill topped by an inukshuk, an ancient, roughly man-shaped Inuit stone marker, and gazed across the sea dotted with dark granite islands bathed in the golden light of dawn.

Our boats full of pots, pails, zinc and plastic wash basins, and large wooden crates, we set out to raid the holms, the rocky islets that are the eiders' favorite nesting places. Men, women, and children stumbled across the algae-slippery coastal rocks of each islet, scrambled up the sheer ice foot, and then spread, screaming with glee, across the island as dozens of eiders, sometimes hundreds, rushed and clattered off their nests. Each nest was lined with a thick, soft layer of brownish gray-flecked eiderdown and contained, on the average, four large olive eggs. The Inuit took the eggs but left the down; traditionally they dressed in furs and had no use for down. Since it was early in the season, most ducks had just laid their eggs.

We rushed from island to island and collected eggs all day, and at night we feasted on them. The children, impatient, pricked many and sucked them dry. The adults preferred them hard-boiled. They made a filling meal; each egg, in volume, equals nearly two hen's eggs, and many Inuit ate six to ten at each meal. The albumen of the hard-boiled eider egg is a smooth, gleaming white, the yolk a vivid orange. The taste is rich and rather oily.

In a week we visited dozens of islets and amassed thousands of eggs. The Inuit also shot at least a hundred ducks and several seals. It seemed amazing that these yearly raids had not decimated the ducks. But they were made so early in the season that most of the robbed ducks probably laid another clutch of eggs.

Killiktee explained to me that in earlier days a taboo forbade the Inuit to camp on eider islands. They visited the islets and took the eggs, but they camped, as we did, only on the largest islands, where few ducks nest, thus avoiding prolonged disturbances in the breeding areas. The ducks, Killiktee said, seemed just as numerous now as sixty years ago when he had first visited the Savage Islands as a boy. Polar bears sometimes swim to the islands, kill all the ducks they can, and eat the eggs. One year, Killiktee said, while the Inuit were on holms, collecting eggs, a polar bear came to camp and robbed their stores. He ate at least a thousand eggs and crushed the rest, leaving a gooey mess upon the beach. Killiktee laughed, amused and without rancor. "Happy bear!" he said.

Less lucky was a gosling caught on an islet by one of the girls. She kept it in a Danish cookie tin and tried to make a pet of it. The fluffy yellow bird peeped pathetically and, inevitably, died after a few days. The girl cried, heartbroken, over her dead pet, and then she skinned it and ate it.

All crates were full of eggs, and ducks, seals, and whale meat filled the boats. The fog rolled in again and our boats traveled through a clammy, grayish, eerie emptiness. Killiktee led, the two other boats followed closely. Dark rocks appeared for moments and vanished into the gloomy gray; ice floes loomed up abruptly. Killiktee never hesitated. "How do you know where to go?" I asked. He smiled. "I know," he said. He had traveled along this coast a long lifetime; he had seen it, memorized it, knew every current, every shoal, every danger spot. He stood in the stern like a graven image and guided our boats through the weird gray void of the fog.

In the evening he veered into a bay, a good place, he said, to catch char on the rising tide. The men set nets, the women boiled pots of meat and tea, the children played. Killiktee, tired, lay down on the shore, and moments later he was sound asleep. A dark shape upon the dark, ice-carved granite, he seemed to meld with rock and land.

Back home at Kiijuak, all eggs were carefully examined. The cracked ones we ate soon. The others were placed in large crates and stored in a cool shady cleft among the rocks. They would last the people in our camp well into the winter.

In fall, an Inuk from Lake Harbour passed our camp and took me along to Aberdeen Bay where the people quarry the jade-green soapstone for their carvings. While he had tea and talked with Killiktee, I packed and carried my things to his boat. Killiktee came to the beach. We both felt awkward. Inuit traditionally joyfully greet visitors, but visitors leave in silence and alone with none to see them off. Their language has many words of wisdom, but none for good-bye.