Recent History

May 12, 1910

Vilhjalmur Stefansson

My Life with the Eskimo - Chapter 11

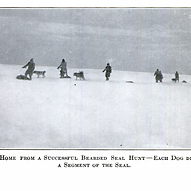

Stefansson meats the Dolphin and Union Strait Eskimo and enjoys a feast of boiled seal meat and blood soup - showcasing the carnivorous diet of these untouched by modern civilization peoples.

Our first day among the Dolphin and Union Straits Eskimo was the day of all my life to which I had looked forward with the most vivid anticipations, and to which I now look back with equally vivid memories, for it introduced me, a student of mankind and of primitive men especially, to a people of a bygone age. Mark Twain's Connecticut Yankee went to sleep in the nineteenth century and woke up in King Arthur's time among knights who rode in clinking mail to the rescue of fair ladies; we, without going to sleep at all, had walked out of the twentieth century into the country of the intellectual and cultural contemporaries of a far earlier age than King Arthur's. These were not such men as Cæsar found in Gaul or in Britain; they were more nearly like the still earlier hunting tribes of Britain and of Gaul living contemporaneous to but oblivious of the building of the first pyramid in Egypt. Their existence on the same continent with our populous cities was an an achronism of ten thousand years in intelligence and material development. They gathered their food with the weapons of the men of the Stone Age, they thought their simple, primitive thoughts and lived their insecure and tense lives — lives that were to me the mirrors of the lives of our far ancestors whose bones and crude handiwork we now and then discover in river gravels or in prehistoric caves. Such archæological remains found in various parts of the world of the men who antedated the knowledge of the smelting of metals, tell a fascinating story to him whose scientific imagination can piece it together and fill in the wide gaps; but far better than such dreaming was my present opportunity. I had nothing to imagine; I had merely to look and listen; for here were not remains of the Stone Age, but the Stone Age itself, men and women, very human, entirely friendly, who welcomed us to their homes and bade us stay.

The dialect they spoke differed so little from the Mackenzie River speech which I had acquired in three years of living in the houses and traveling camps of the western Eskimo that we could make ourselves understood from the first. It cannot have happened often in the history of the world that the first white man to visit a primitive people was one who spoke their language. My opportunities were therefore unusual. Long before the year was over I was destined to become as one of them, and even from the first hour we were able to converse sympathetically on subjects of common concern. Nothing that I have to tell from the Arctic is of greater intrinsic interest or more likely to be considered a contribution to knowledge than the story of our first day with these people who had not, either they or their ancestors, seen a white man until they saw me. I shall therefore tell that story.

Like our distant ancestors, no doubt, these people fear most of all things the evil spirits that are likely to appear to them at any time in any guise, and next to that they fear strangers. Our first meeting had been a bit doubtful and dramatic through our being mistaken for spirits, but now they had felt of us and talked with us, and knew we were but common men. Strangers we were, it is true, but we were only three among forty of them, and were therefore not to be feared. Besides, they told us, they knew we could harbor no guile from the freedom and frankness with which we came among them; for, they said, a man who plots treachery never turns his back to those whom he intends to stab from behind.

Before the house which they immediately built for us was quite ready for our occupancy, children came running from the village to announce that their mothers had dinner ready. The houses were so small that it was not convenient to invite all three of us into the same one to eat; besides, it was not etiquette to do so, as we now know. Each of us was, therefore, taken to a different place. My host was the seal-hunter whom we had first approached on the ice. His house would, he said, be a fitting one in which to offer me my first meal among them, for his wife had been born farther west on the mainland coast than any one else in their village, and it was even said that her ancestors had not belonged originally to their people, but were immigrants from the westward. She would, therefore, like to ask me questions.

It turned out, however, that his wife was not a talkative person, as, but motherly, kindly, and hospitable, like all her countrywomen. Her first questions were not of the land from which I came, but of my footgear. Weren't my feet just a little damp, and might she not pull my boots off for me and dry them over the lamp? Would I not put on a pair of her husband's dry socks, and was there no little hole in my mittens or coat that she could mend for me? She had boiled some seal-meat for me, but she had not boiled any fat, for she did not know whether I preferred the blubber boiled or raw. They always cut it in small pieces and ate it raw themselves; but the pot still hung over the lamp, and anything she put into it would be cooked in a moment.

When I told her that my tastes quite coincided with theirs in fact, they did — she was delighted. People were much alike, then, after all, though they came from a great distance. She would, accordingly, treat me exactly as if I were one of their own people come to visit them from afar and, in fact, I was one of their own people, for she had heard that the wicked Indians to the south spoke a language no man could understand, and I spoke with but a slight flavor of strangeness.

When we had entered the house the boiled pieces of seal-meat had already been taken out of the pot and lay steaming on a sideboard. On being assured that my tastes in food were not likely to differ from theirs, my hostess picked out for me the lower joint of a seal's fore leg, squeezed it firmly between her hands to make sure nothing should later drip from it, and handed it to me, along with her own copper-bladed knife; the next most desirable piece was similarly squeezed and handed to her husband, and others in turn to the rest of the family. When this had been done, one extra piece was set aside in case I should want a second helping, and the rest of the boiled meat was divided into four portions, with the explanation to me that there were four families in the village who had no fresh seal-meat. The little adopted daughter of the house, a girl of seven or eight, had not begun to eat with the rest of us, for it was her task to take a small wooden platter and carry the four pieces of boiled meat to the four families who had none of their own to cook. I thought to myself that the pieces sent out were a good deal smaller than the individual portions we were eating, and that the recipients would not get quite a square meal; but I learned later that night from my two companions that four similar presents had been sent out from each of the houses where they were eating, and I know now that every house in the village in which any cooking was done had likewise sent four portions, so that the aggregate must have been a good deal more than the recipients could eat at one time. During our meal presents of food were also brought us from other houses; each housewife apparently knew exactly what the others had put in their pots, and whoever had anything to offer that was a little bit different would send some of that to the others, so that every minute or two a small girl messenger appeared in our door with a platter of something to contribute to our meal. Some of the gifts were especially designated as for me — mother had said that however they divided the rest of what she was sending, the boiled kidney was for me; or mother had sent this small piece of boiled seal flipper to me, with the message that if I would take breakfast at their house to-morrow I should have a whole flipper, for one of my companions was over at their house now, and had told them that I considered the flipper the best part of a seal.

As we ate we sat on the front edge of the bed-platform, holding each his piece of meat in the left hand and the knife in the right. This was my first experience with a knife of native copper; I found it more than sharp enough and very serviceable. The piece of copper (float) from which the blade had been hammered out had been found, they told me, on Victoria Island to the north in the territory of another tribe, from whom they had bought it for some good drift wood from the mainland coast. My hostess sat on my right in front of the cooking-lamp, her husband on my left. As the house was only the ordinary oval snow dome, about seven by nine feet in inside dimensions, there was only free room for the three of us on the front edge of the two-foot-high snow platform, over which reindeer, bear, and musk-ox skins had been spread to make the bed. The children, therefore, ate standing up on the small, open floor space to the right of the door as one enters; the lamp and cooking-gear and frames for drying clothing over the lamp took up all the space to the left of the door. In the horseshoe-shaped, three - foot-high doorway stood the three dogs of my host, side by side, waiting for some one to finish the picking of a bone. As each of us in turn finished a bone we would toss it to one of the dogs, who retired with it to the alleyway, and returned to his position in line again as soon as he had finished it. When the meal was over they all went away unbidden, to curl up and sleep in the alleyway or out-of-doors.

Our meal was of two courses : the first, meat; the second, soup. The soup is made by pouring cold seal blood into the boiling broth immediately after the cooked meat has been taken out of the pot, and stirring briskly until the whole comes nearly (but never quite) to a boil. This makes a soup of a thickness comparable to our English pea-soups, but if the pot be allowed to come to a boil, the blood will coagulate and settle to the bottom. When the pot lacks a few degrees of boiling, the lamp above which it is swung is extinguished and a few handfuls of snow are stirred into the soup to bring it to a temperature at which it can be freely drunk. By means of a small dipper the housewife then fills the large musk-ox-horn drinking-cups and assigns one to each person; if the number of cups is short, two or more persons may share the contents of one cup, or a cup may be refilled when one is through with it and passed to another. After I had eaten my fill of fresh seal-meat and drunk two pint cupfuls of blood soup, my host and I moved farther back on the bed platform, where we could sit comfortably, propped up against bundles of soft caribou-skins, while we talked of various things. He and his wife asked but few questions, and only such as could not be considered intrusive, either according to their standards as I learned them later or according to ours. They understood perfectly, they said, why we had left behind the woman of our party when we came upon their trail, for it is always safest to assume that strangers are going to prove hostile; but now that we knew them to be harmless and friendly, would we not allow them to send a sled in the morning to bring her to the village? They had often heard that their ancestors used to come in contact with people to the west, and now it was their good fortune to have with them some men from the west, and they would like to see a western woman, too. It must be a very long way to the land from which we came; were we not satiated with traveling, and did we not think of spending the summer with them ? Of course, the tribes who lived farther east would also be glad to see us, and would treat us well, unless we went too far to the east and fell in with the Netsilik Eskimo ( King William Island ), who are wicked, treacherous people who strange to say have no chins. Beyond them, they had heard, lived the white men (Kablunat), of whom, no doubt, we had never heard, seeing we came from the west, and the white men are farthest of all people to the east. They are said to have various physical deformities; they had heard that some of them had one eye in the middle of the forehead, but of this they were not sure, because stories that come from afar are always doubtful. The white men were said to be of a strangely eccentric disposition; when they gave anything to an Eskimo they would take no pay for it, and they would not eat good, ordinary food, but subsisted on various things which a normal person could not think of forcing himself to swallow except in case of starvation. And this in spite of the fact that the white men could have better things to eat if they wanted to, for seals, whales, fish, and even caribou abound in their country.

May 20, 1910

Vilhjalmur Stefansson

My Life with the Eskimo - Chapter 13

All of the caribou were skin-poor and the marrow in their bones was as blood, but we had with us plenty of seal oil from seals killed farther west along the coast, so that the two together made a satisfactory diet.

As we proceeded east along Dolphin and Union Straits from Cape Bexley, we found here and there traces of Eskimo parties who were going in from their winter hunt on the sea ice to cache their clothing, household property, and stores of oil on the beach preparatory to moving inland for their summer caribou hunt. Some of these groups we never saw at all; the trails of others we picked up and followed until we overtook the parties, who were usually camped on the shore of a small lake, where they were fishing with hooks through holes they had made with their ice-picks in the seven-foot-thick ice. The caribou in this district are scarce in spring and difficult to get by the hunting methods of the Eskimo. Fish were not secured in large numbers, either, for these people know nothing of nets. Our archæological investigations have shown us that the knowledge of fishing by nets never extended farther east along the north shore of the mainland than Cape Parry, and the Copper Eskimo have no method of catching fish except that of hooks and spears. The hooks are, like most of their weapons, made of native copper. They are unsuited for setting, for there is no barb, and unless the fish be pulled out of the water as soon as he takes the hook he is sure to get off again.

West of Cape Bexley we had seen no traces of caribou for a hundred and fifty miles, but as soon as we came to where the straits began to narrow, east of Cape Bexley, we began to find more and more frequently the tracks of the northward migrating bands of cow caribou bound for Victoria Island. At first we did not see on an average more than ten or fifteen animals a day, but later on they increased in number; and with our excellent rifles we found not the slightest difficulty in supplying ourselves with plenty of venison and in having enough to spare to feed also the people at whose villages we visited.

In coming to the coast from the south, caribou take the ice with out hesitation. It cannot be that they see land to the north of the straits, for half of the time, at least, the land is hidden in a haze, even from the human eye, which is far keener than that of the caribou. Neither can it be the sense of smell that guides them, for the northward direction of their march is not interfered with by change of wind. They will sometimes go ten miles out on the ice and lie down there, then wander around in circles for several hours or half a day, and finally proceed north again. Both at Liston and Sutton islands, in Simpson Bay, and farther east at Lambert Island, we saw caribou march right past without paying any attention to the islands, although there was food upon them , and they in some cases passed within a hundred yards or so. The bands would generally be from five to twelve caribou, consisting in the main of females about to drop their fawns, but also of yearlings and two-year-olds of both sexes. All of them were skin-poor and the marrow in their bones was as blood, but we had with us plenty of seal oil from seals killed farther west along the coast, so that the two together made a satisfactory diet. The skins at this season of the year are worth less, partly because the hair is loose, but also because they are full of holes, ranging in size from that of a pea to that of a navy bean, from the grubs of the bot-fly which infest the backs of the animals. When spread out to dry, the skin of the spring-killed caribou looks like a sieve.

July 1, 1910

Vilhjalmur Stefansson

My Life with the Eskimo - Chapter 13

In summer we much preferred wolf meat to caribou, for it is usually tender and fat, and the caribou, all except the oldest bulls, are in very indifferent condition. We never ate venison when there was wolf meat to be had at this season

I was about to shoot, and he was so near that there was no doubt of the result, when suddenly, almost in line with the hare, I saw a caribou disappearing over a ridge. He evidently had seen me while my attention was concentrated on the hare and while I was exposed against the sky-line on top of the rock ridge along which the hare was running. Of course I gave no further thought to the hare. Caribou, when they merely see a man and do not get his wind, ordinarily do not run far, and within an hour I had come up to this one again. It turned out I had seen only one of two animals, both of which I now found quietly feeding upon a level spot - so level, indeed, that it took several hours of careful stalking before I got within range. The animals proved to be two young bulls, skin-poor, with the mar row as blood in their bones. Nevertheless there was great rejoicing in camp when I returned , after being out about twenty-four hours, with a back-load of caribou meat. I have found that Eskimo in a strange country are typically sceptical of the possibilities of finding food, and my people had several days ago made up their minds that all the caribou had left the district and we were destined to have to live the whole summer on squirrels and ptarmigan.

Natkusiak had not yet returned when I got home, and it was nearly another twenty-four hours before he put in an appearance, but he had been more successful than I in securing three old bull caribou which were in fair condition at this season of the year, and best of all he had shot a wolf that was as fat as a pig. In summer we much preferred wolf meat to caribou, for it is usually tender and fat, and the caribou, all except the oldest bulls, are in very indifferent condition. We never ate venison when there was wolf meat to be had at this season; at least that was true of all of us except Pannigabluk, to whose family and ancestors the wolf is taboo.

As the caribou killed by Natkusiak were in a southeasterly direction, we brought into camp at once the meat of the two that I had killed, and then proceeded farther upstream to a point from which it was only seven or eight miles to where Natkusiak had cached the other meat. We learned that at this season the caribou in the Coppermine country were all bulls, and none of them were moving. In general singly, or by twos and threes, they had taken possession of some snow-bank protected from the sun by a northward-facing precipice, and there they stayed. They would feed for an hour or two on the grass or moss in the neighborhood, and then go back to lie on the snow, where they had a measure of protection from the clouds of mosquitoes, and where the intense heat of the sun was more bearable to them.

On an average the number of caribou was not more than about one for every hundred square miles of country, and we always had to go south to kill the next one. Occasionally either Natkusiak or myself would hunt back downstream twenty or thirty miles, with the idea that caribou might have moved in behind us, but with no result; and each time we killed a caribou to the south and moved up to get its meat we got that much farther from our sled cache and from my camera and writing materials; so that by the latter part of June it had become evident that we should never be able to go back to the cache during the summer, for to go back meant starvation . By killing the caribou as we went we had burned our bridges behind us.

Later on, after we had succeeded in joining the Eskimo, there was scarcely a half-hour when some picturesque or unusual scene in their lives during the summer did not bring back to me the absence of my camera. As for my diary for the summer, it was written in my small pocket notebook in so microscopic a hand that it is difficult to read without a magnifying glass, and even so I had to trust to my memory for many things that in ordinary course I should have recorded.

July was intolerably hot. We had no thermometer, but I feel sure that many a day the temperature must have been over one hun dred degrees in the sun, and sometimes for weeks on end there was not a cloud in the sky. At midnight the sun was what we would call an hour high, so that it beat down on us without rest the twenty four hours through. The hottest period of the day was about eight o'clock in the evening, and the coolest perhaps four or five in the morning. The mosquitoes were so bad that several of our dogs went completely blind for the time, through the swelling closed of their eyes, and all of them were lame from running sores caused by the mosquito stings on the line where the hair meets the pad of the foot. It is true that on our entire expedition we had no experience that more nearly deserved the name of sufferingthan this of the combined heat and mosquitoes of our Coppermine River summer.

By the last week in July we had proceeded upstream as far as the mouth of the Kendall River, which flows in from the west from Dismal Lake. We had continually been putting off the crossing of the river, hoping to find a better place, and also being in no hurry, for we did not think the Rae River Eskimo whom we wanted to join would reach Dismal Lake before early August. We finally selected for the crossing a strip of river where there is half a mile of quiet water between two strong rapids, built a raft from dry spruce grow ing near the river, and got across with all our belongings, including at that time about three hundred pounds of dry caribou meat. Immediately upon landing on the west side we cached the meat safely in a rock crevice, under huge stones, intending it for a store against some future emergency, but our fortunes that summer never brought us back to the place again; so doubtless it is there yet unless some wandering Eskimo may have happened to find it.

On the north shore of Dismal Lake, which we reached in a two days march from the Coppermine, we ran completely out of food for the only time in our period of fourteen months of absence from our base at Langton Bay. Of course, in an extremity we could have gone back to where we had cached the dried meat two days before, but our general policy was never to retreat, for we knew well that the chances of food ahead were always a little better than behind. The morning of July 29th I broke the rule against shooting ptarmigan, and used one of my valuable Mannlicher-Schoenauer bullets to secure half a pound of meat. That half-pound was the breakfast for the four of us, and the dogs, poor fellows, got nothing. But our fortune was soon to turn, for when immediately after breakfast I climbed the high hill behind our camp I saw a caribou coming from the north and disappearing among some hills to the east in a way to make it uncertain in just what direction he was going. The three of us therefore started to meet him by different routes. It happened that I was the one to get sight of him first, and it turned out he had a companion that must evidently have preceded him into the hills a moment before I turned my field glasses that way. The two of them were in good flesh, so that by four in the afternoon both ourselves and our dogs had had a square meal of better meat than ordinary.

August 1, 1910

Vilhjalmur Stefansson

My Life with the Eskimo - Chapter 14

Spending the summer with the Copper Eskimo, Stefansson learned they also survived through hunting and eating game and they treated him as one of their own, despite his magic usage of a rifle. They also had no use for white man's food of flour and sugar, but considered it it a great gift to distinguish them from those who had nothing.

The summer spent with the Copper Eskimo between Bear Lake and the Coppermine River had passed pleasantly for me, and profitably. From the first they had accepted me as one of them they had not known that I was a white man until I told them so. My life was exactly as theirs in that I followed the game and hunted for a living. Even my rifle did not differentiate me from them, because they looked upon its performances as my magic, differing in no way essentially from their magic. I spoke the Mackenzie Eskimo dialect and made no attempt to learn theirs, for it was not necessary for convenience' sake, and it would have thoroughly confused me to try to keep two so similar dialects separate in my mind. Sometimes in meeting an utter stranger I found a little difficulty; not that it was difficult for me to understand him, for he spoke very much like all the others that I had dealt with, but he at first would have some difficulty in adjusting himself to the sort of language spoken by myself and my companions.

By August the caribou skins were suitable for clothing. Up to that time we had killed only for food and had eaten each animal before moving to where the next was killed, so that our baggage had not increased; but now we had to begin saving the skins against the winter, and by the latter part of August we had a bundle of some thing like forty of the soft, short-haired pelts, so that our movements began to be hampered by the bulk and weight of our back-loads. We therefore chose a large dead spruce, the trunk of which was free of bark and limbs, and fifteen feet up it we suspended our bundle of skins. This we did for fear of the wolverines, for the Indians say that the wolverine cannot climb a smooth tree-trunk if the tree be so stout that it is unable to reach half around it with its legs in trying to climb. In this I have not much faith, because I have seen so many caches made which the Indians and Eskimo say are perfectly safe, and later when the cache is found to be rifled, the natives are invariably astounded and assure you that they never heard of such a thing before. We tied our bundle with thongs to the trunk of the tree, and three weeks later when we came back it turned out that the first wolverine had just that day climbed up and eaten some of the thongs. Apparently it was mere accident that protected our clothing materials, and had we come a day later we might have found the skins destroyed.

The summer had been one of continuous sunshine, but that changed with the month of September, and the mists and fogs were then almost as continuous as the sunshine had been. The rutting season had commenced, and the bull caribou, which were numerous in summer in all the wood fringe northeast of Bear Lake, had moved out in the open country, and the hunting had become more difficult. Finally, by the end of September the caribou had become very few in number.

The Eskimo had all summer been making sledges, wooden snow shovels, bows and spear handles, and other articles of wood. All these things and a good supply of caribou meat were stored at a spot which we called the “ sled-making place, ” but which the Slaveys of “ Big Stick Island.” This is a clump of large spruce trees on the southeast branch of the Dease River. The Eskimo were now waiting for the first snow of the year so they could hitch their dogs to the sleds they had made, load their provisions upon them, and move north toward the coast where they expected to spend the winter in sealing. But starvation began to threaten, so that finally, on September 25, the last party started toward the coast, carrying their sleds on their backs, for the first snow had not yet fallen.

I wanted very much to accompany them, to become as familiar with their winter life as I already was with their summer habits, but it did not seem a safe thing to try, for their only source of food in winter is the seal, and these must be hunted, under the peculiar Coronation Gulf conditions, by methods unfamiliar to my companions and myself. Of course, we could have learned their hunting methods readily enough, but they told us that almost every winter, in spite of the most assiduous care in hunting, they are reduced to the verge of starvation. Frequently (and it turned out to be so that winter) they have to eat the caribou sinew they have saved up to use as sewing-thread, the skins they have intended for clothing, and often their clothing, too, while about one year in three some of their dogs die of hunger; a few years ago about half of one of the larger tribes starved to death. It was both fear of actual want and fear that if want came their superstition would blame us for it that kept us from going to the sea-coast with them. We decided, therefore, to winter on the head-waters of the Dease River, where the woodland throws an arm far out into the Barren Ground; to try to lay up there sufficient stores of food for the winter; to pass there the period of the absence of the sun; and to join the Coronation Gulf Eskimo in March, when abundance of hunting -light would make it safer to go into a country poorly stocked with game.

When we had decided upon this, I left my Eskimo to build a winter hut, while I walked alone down to the mouth of the Dease River, a distance of about thirty miles, to where my friends Melvill and Hornby were going to have their winter camp. I found there also Mr. Joseph Hodgson with his family, consisting of his wife, son, daughter, and nephew. Mr. Hodgson is a retired officer of the Hudson's Bay Company, who, through the many years of his service on the Mackenzie River, had had a longing to get out of the beaten track of the fur-trader. For many years, he told me, it had been his special dream to spend the winter on the Dease River, and he had now come to do it. The mouth of the Dease is a picturesque spot, and although the Indians told Mr. Hodgson that it was “ no good” as a fishing place or as a location for hunting or trapping, he nevertheless stuck to his original intention and built his house there.

Both Mr. Hodgson and the Englishmen who lived about three miles away from him had a small store of white men's food, such as flour, sugar, tea, salt, and the like. But these were articles we did completely without, and even to the others they were merely luxuries, for they had to get the main part of their food-supply from the caribou of the land and the trout of Bear Lake. In spite of the little they had they offered me a share, a thing that I much appreciated, both because it shows the spirit of the North and because my Eskimo were immeasurably gladdened by a little flour, a thing they had not expected and without which they can get along very well, but the possession of which they feel marks them off definitely from the poor trash who cannot afford such things.

December 4, 1910

Vilhjalmur Stefansson

My Life with the Eskimo - Chapter 14

"The main part of the food was whale, the carcass of which had drifted into the beach just before the freeze-up in the fall. This animal had been freshly killed when he drifted ashore, and furnished us, therefore, a supply of food which was not only abundant but also palatable." The challenges of hunting caribou and camping in the cold are also covered.

Before quite reaching Langton Bay harbor, however, we came upon sled tracks, and at the harbor itself we found Dr. Anderson and our Eskimo safe, comfortably housed and fairly well supplied with food. The main part of the food was whale, the carcass of which had drifted into the beach just before the freeze-up in the fall. This animal had been freshly killed when he drifted ashore, and furnished us, therefore, a supply of food which was not only abundant but also palatable. I found here waiting for me some mail, to get which Dr. Anderson had had to make a thousand-mile trip the previous summer west to the whaling-station at Herschel Island. My most recent letter had been written on the 13th of May, 1910, and it was now the 4th of December.

After resting about two weeks we started back toward Bear Lake, leaving the same four Eskimo behind, although Dr. Anderson accompanied us. Knowing the character of the country, and having plenty of food at Langton Bay, we loaded the sleds with provisions, which, together with the caribou meat we had cached inland, would be equal to about twenty-five days' full rations. Had everything on the homeward road been as it was on the northwestward journey, this would have been ample, for we had come from Bear Lake to the sea in twenty-six days, but we were now a month later in the season; the sun had long ago gone away and we had only twilight at noon, and the snow lay thick and soft in many places in the river where on the way north there was glare ice. Our progress southward was therefore very slow, and by the time we reached that point of Horton River where one begins the portage to Bear Lake we were on short rations again. In our two days' crossing of the Barren Ground we again had a blizzard, but again it happened to be blowing at our backs and rather helped than hindered us, although we could see practically nothing of the country through which we traveled.

On our second day in the Barren Ground we had the last and most striking proof of Johnny's infallibility. We had come to perhaps a dozen trees, and I said to Johnny, “ Well, this is fine; now we are back in your Bear Lake woods again." No, that was not so, he said. There were two ranges of hills on the Barren Ground. One of these was right in the middle of the Barren Ground, and on the southerly slope of this range were a few trees. It was at these trees we now were, and if we left them, it would take us another whole day of travel before we came to the next. He told us, therefore, that unless we wanted to camp without firewood we must camp here. Dr. Anderson and I talked this over, and we agreed that Johnny had never in the past proved right in anything; but still it seemed better to do as he advised, for, after all, this was his own country, and he ought to know something about it. The blizzard was still blowing, and it was intensely cold. If we had pitched camp where there were no trees we should have made a small tent, Eskimo fashion, and it would have taken us only a few moments to do so; but now that we had trees we put up an Indian-style tepee, a difficult thing to do in a storm, and a matter of two hours or so of hard work during which all of us froze our faces several times and suffered other minor inconveniences. My idea had been, on seeing these few trees, that we were now on the edge of the forest, and that a few miles more of travel would bring us into the thick of woods where no wind can stir the snow; and in the morning when we awoke and looked out, sure enough, there was the edge of the forest only a few hundred yards away, with the woods stretching black and unbroken toward Bear Lake. But for the wisdom of Johnny Sanderson we might have camped in its shelter and escaped one of the most disagreeable camp making experiences we ever had.

The next day we had traveled only a few miles before we came upon the tracks of caribou. Our thermometer had broken some time before, and so I speak without the book, but there is little doubt that the temperature was considerably below 50 ° Fahrenheit. There was not a breath of air stirring. While the other three proceeded with the sled I struck out to one side to look for caribou. First I saw a band that had been frightened by our main party. There were only a few clearings in the woods, but wherever the animals were you could discover their presence by the clouds of steam that rose from them high above the tops of the trees.

There are few things one sees in the North so nearly beyond belief as certain of the phenomena of intense cold as I saw and heard them that day. It turned out that the woods were full of caribou, and wherever a band was running you could not only see the steam rising from it and revealing its presence, even on the other side of a fairly high hill, but, more remarkable still, the air was so calm that where an animal ran past rapidly he left behind him a cloud of steam hovering over his trail and marking it out plainly for a mile behind him. When you stopped to listen, you could hear the tramp of marching caribou all around you. On such days as this I have watched caribou bands a full mile away whose walking I could hear distinctly although there was no crust on the snow; and as for them, they could not only hear me walking, but could even tell the difference in the sounds of my footsteps from those of the hundreds of caribou that were walking about at the same time.

My first opportunity to shoot came through my hearing the approach of a small band. I stopped still and waited for them. I was not nervous, but rather absent-minded. In other words, my mind was more fully occupied than it should have been with the importance of getting those particular caribou. I always carry the magazine of my rifle full but the chamber empty, and as the animals approached I drew back the bolt to throw a cartridge into the chamber, but when I tried to shove the bolt forward it stuck fast. This is the only time in four years of hard usage that anything has interfered with the perfect working of my Mannlicher-Schoenauer. The caribou were moving past without seeing me, and I became a bit excited. I knew the rifle was strong, and I hammered on the end of the bolt with the palm of my hand, but it would not move. When the caribou were finally out of range and when nothing more could be done, I for the first time took a good look at the rifle to try to discover the trouble, and saw that one side of the bolt had something frozen fast to it. It turned out that when I had drawn the bolt back to load the rifle I had carelessly allowed the palm of my bare hand to rest against the bolt, and a piece of skin about an inch long and a quarter of an inch wide had frozen fast to the bolt and been torn away from my hand without my noticing it. It took but a few moments scraping with my hunting knife to remove the blood from the bolt, and the rifle was in good working order again.

Three days later we reached the house of Melvill and Hornby on Bear Lake, thirty-three days after leaving Langton Bay. After a short visit with them and Mr. Hodgson we proceeded up the Dease River and found Tannaumirk and Pannigabluk well, although getting short of food, for Tannaumirk was not a hunter of much enterprise.

No caribou were just then to be found near our winter quarters, so Dr. Anderson, one of the Eskimo, and myself struck out south to look for them. On the second day we found them near the northeast corner of Bear Lake, but had hard luck that day on account of variable faint airs that continually gave the animals our wind. The next day, however, we got sixteen, and within the next twenty days thereafter fifty -two more, which was plenty of meat for the rest of the winter.