Recent History

January 1, 1911

Vilhjalmur Stefansson

My Life with the Eskimo - Black, Brown, Polar Bears

The habits of black bears, brown bears, and polar bears are described as they relate to Eskimo life.

Ursus americanus Pallas. Black Bear.

The Black Bear is very common along the Athabaska River, and we saw eight Bears in less than four hours of drifting on the river below the Grand Rapids, May 14th , 1908. This part of the Atha baska has the reputation of being the best place for Black Bears in North America. They are seen most abundantly just after the ice goes out in the spring and they come down to the edge of the river to look for dead fish which have been pushed up by the ice . In the fall the tangled brushy slopes along the Athabaska are said to be much frequented by Black Bears which feed largely on blueberries at that season . It is, however, more difficult to see the Bears in autumn on account of the thickness of the underbrush . Black Bears are said by the Indians to be fairly common around Great Bear Lake and occasionally north to the Mackenzie delta .

Ursus richardsoni Swainson . Barren Ground Bear. Ak'lak (Es kimo name for Brown Bear from Bering Sea to Coronation Gulf).

Brown Bears, or Grizzlies, are found sparingly throughout the Arctic mainland from western Alaska to Coronation Gulf. There are undoubtedly two or three races or species in this region , but, owing to lack of specimens from important localities and lack of time for critical examination of the material at hand, I am obliged to nominally refer to the Arctic Brown Bears under the above heading. In northern Alaska they do not appear to be very common on the north side of the Endicott Mountains, and seldom, if ever, come out on the coastal plains. The inland Eskimo occasionally kill specimens and often use the skin for a tent door. I saw the skins of two which were killed on the Hula-hula River, in October, 1908, by a Colville River Eskimo named Auktel'lik. Auktel'lik told me he had killed forty four Aklak in his time, and that only two of the lot came towards him and tried to attack him. From what I could learn he had not hunted very far west of the Colville or at all east of the Mackenzie. Most Eskimo, however, speak with much greater respect of the pugnacity of Aklak than of Nannuk (the Polar Bear) and are much more cautious about attacking him. On July 3d, 1912, Mr. Frederick Lambart, Engineer on the Alaska - Yukon Boundary Survey, shot a Brown Bear on the Arctic slope of the mountains on the 141st meridian, about forty - five miles from the Arctic Ocean at Demarcation Point. From three photos of the dead Bear, it appeared to be of the long -nosed type, with a pronounced hump on the shoulders. Mr. Lambart informs me that this bear has been examined by Dr. C. Hart Merriam and declared to be a new species hitherto undescribed . In the Mackenzie delta tracks of Brown Bears are occasionally seen, but the bears are seldom killed, owing to the impracticability of hunting them through the dense underbrush on the islands in summer.

I have been warned many times by natives against shooting at a Barren Ground Bear unless from above — as a wounded bear has greater difficulty in charging uphill. So far as our experience goes, however, the Barren Ground Bear is an inoffensive and wary brute, preferring to put as much ground as possible between himself and human society. I saw but one unwounded bear come towards me, but as he did not have my scent his advance was perhaps more from mere curiosity than from hostility. As the bear was on the uninhabited coast between Cape Lyon and Dolphin and Union Straits, and he had probably never seen human beings before, this inference seems plausible . Wounded bears are another story, of course, and it is generally admitted that the Barren Ground Bears are tougher or more tenacious of life than the Polar Bears.

We found the center of greatest abundance of the Barren Ground Bears in the country around Langton Bay and on Horton River, not more than thirty or forty miles south from Langton Bay. One was killed at Cape Lyon, and another on Dease River east of Great Bear Lake. In this region our party killed about twenty specimens, most of which were obtained on our dog-packing expeditions in early fall. The Bears here showed two very distinct types, which for convenience we designate as the long -snouted and short- snouted types. The skulls are readily separated on this basis. It is rather hard to distin guish them by color, as late summer skins are usually much bleached out. In general the long-snouted Bears were inclined to a reddish brown cast of color ( sometimes almost bay color) , while the others were often very dark —dusky brown, with tips of hairs on dorsal surface light grayish brown on fulvous, sometimes with tips a faint golden yellowish tint. The Barren Ground Bears go into hibernation about the first week of October and come out early in April while the weather is still very cold .

While ascending the Horton River we saw at intervals the nearly fresh tracks of three Barren Ground Bears on December 29th, 1910, and January 1st, 1911, going along the river and over the shortest portages, at least forty miles in approximately a straight line. Neither the Eskimo or the Slavey Indian who were with us had ever before seen evidences of Brown Bears out of their holes in midwinter. They seem to be nearly as fat on their first emergence from their long sleep as in the fall, but speedily lose weight, and early summer specimens are invariably poor. This is natural from the nature of their food , which is to a large extent vegetable. Although the Bear's native heath is often conspicuously furrowed in many places by the unearthed burrows of Arctic spermophiles (Citellus parryi or C. p. kennicotti) I believe that the Bear's search is more for the little mammal's store of roots than for the little animal itself. The Bear's stomach is much more apt to contain masu roots (Polygonum sp. ) than flesh . A bear must needs be very active to catch enough spermophiles above ground in spring and early summer, and if carcasses are not to be found, the Bears evidently suffer most from hunger at this season, when they can neither dig roots for themselves in the frozen ground nor dig out the spermophiles and their caches. One specimen was killed by an Eskimo of our party on Dease River, east of Great Bear Lake, after the Bear had gorged himself on a cache of Caribou meat, having more than fifty pounds of fresh meat in his stomach. A few Bears were met with in the Coppermine country, but throughout the Coronation Gulf region they are apparently rare. The Eskimo say that the Aklak is not found on Victoria Island. The fact that the Barren Ground Bears seem to always have at least two cubs at a birth, that old bears are often seen followed by two young cubs and one yearling cub, and that we never saw more than one yearling cub accompanying its mother, is evidence that there must be considerable mortality among the cubs in the first year, probably during the second spring. The new -born cubs, of course , are nursing in the spring, while the older cubs presumably have to depend upon their own foraging. Otherwise these Bears have practically no enemies besides man. As there is little market for their skins, neither Eskimo nor Indians make any special effort to hunt them, the specimens obtained being in general upon summer Caribou hunts.

Thalarctos maritimus ( Phipps) . Polar Bear. Nan'nuk (all Eskimo dialects) .

The Polar Bear or White Bear is a circumpolar cosmopolitan, although seldom found very far from the sea ice. In winter these bears are apt to appear anywhere along the coast, but in summer their occurrence depends largely upon the proximity of pack ice. Along the Arctic coast of Alaska, east of Point Barrow , the species is not very abundant, and the same may be said of the coast east and west of the Mackenzie delta. Numbers are annually killed near Cape Bathurst. The Polar Bears seem to be most abundant around Cape Parry and the southern end of Banks Island, very rarely passing through Dolphin and Union Straits, into Coronation Gulf. Around Cape Parry, in August, 1911 , we saw fourteen Bears within two days roaming about the small rocky islands, evidently marooned when the ice left the beach. They are often seen swimming far out at While whaling about twenty miles off Cape Bathurst ( the nearest land) and about five miles from the nearest ice mass, we saw a Polar Bear which paddled along quite unconcernedly until he winded the ship, then veered away, heading out toward the ice pack . Shortly before Christmas an officer from the schooner Rosie H., with a party of Eskimo, killed a female and two newly born cubs in a hole in the snow near the mouth of Shaviovik River, west of Flaxman Island. It was said to be unusual for a Polar Bear to have cubs so early in the winter.

February 20, 1911

Vilhjalmur Stefansson

My Life with the Eskimo - Moose

The moose is not populous enough to warrant much hunting by the Eskimo.

Alces americanus Jardine. Eastern Moose. Tûk'tū - vûk ( Alaskan , Mackenzie, and Coronation Gulf Eskimo). Ko-gon (Slavey Indian).

The Moose is common throughout the timbered country all along the Mackenzie River, and has occasionally been seen north of the timber line near Richard Island. According to the opinion of old residents and to data collected by the expedition, the Moose is increasing all through the northern country as well as extending its range rapidly and noticeably. Owing to its solitary habits and the nature of its habitat, the Moose cannot be slaughtered wholesale as can the Caribou and the Musk-ox, and the northern Indians have decreased in numbers at such a rapid rate as to more than compensate for the increased killing power of their more modern weapons. Moose venture very rarely into the region of the lower Horton River. Mr. Joseph Hodgson, one of the oldest of Hudson Bay traders, says that in the early days, up to less than fifty years ago, Moose were very rarely seen east of the Mackenzie, and told us in 1911 that it was only within the past half-dozen years that Moose had been seen on the east side of Great Bear Lake. Moose are now fairly numerous on Caribou Point, the great peninsula between Dease Bay and McTavish Bay, Great Bear Lake, and on the Dease River, northeast of Great Bear Lake. A Coronation Gulf Eskimo from the region near Rae River (Pal'lirk) told us that he had seen two Moose (which he thought cows, from their small antlers) near the mouth of Rae River in 1909 or 1910. These Eskimo often hunt in summer down to Great Bear Lake and know the Moose from that region. Rae River flows into the southwestern corner of Coronation Gulf, and the Moose undoubtedly wandered here from the region around Great Bear Lake.

March 22, 1911

Vilhjalmur Stefansson

My Life with the Eskimo - Chapter 15

"Two caribou were hardly sufficient meat to go on with, so that I went across the Horton River a mile or two east of where the Eskimo went to get the cached meat, and shot three caribou and a fine specimen of white wolf. This wolf was not only fat and excellent eating..."

When about four miles from the eastern end of the lake we left it, striking off on the north side to make a short cut along the southern side of some steep hills which run east towards the Coppermine. We were traveling now on high ground and could see south across the valley of the Kendall bands of caribou grazing about six miles away. We accordingly camped, for our meat had about run out and it seemed well to replenish our stores.

I happened at this juncture to be suffering from a chafed foot on account of having worn a badly made stocking the day we left home. Dr. Anderson and Natkusiak therefore undertook to hunt, and I stayed at home to give my foot a chance to recover. Tannaumirk, who was a fair seamstress, also stayed at home mending boots and stockings and incidentally telling me folk-lore stories which I wrote down in the original language as he told them. Tannaumirk could never be relied upon for an enterprise of moment, but he had many good qualities, among which were an unvarying cheerfulness and an inexhaustible fund of folk-lore tales, songs, and charms, which he had at first, like the rest of his countrymen, been loath to repeat to me on account of being used to having white men make game of him for doing so. But now that he had found that I had a real interest in such things he never tired of telling them.

In the evening when our hunters came home they reported having seen caribou in great numbers, but they had not had the best of luck. Dr. Anderson had shot two and Natkusiak had failed to get any. It had been a bright sunshiny day and Dr. Anderson had carelessly gone without glasses, with the result that he was slightly snow blind the following morning.

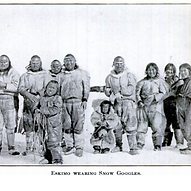

Seeing that the subject has been mentioned, it may be worthwhile to say that we have tried glasses of all colors and makes and have found the amber ones, made on the same principle as light filters for cameras, to be far superior to blue, green, plain smoked, or any other variety. The Eskimo goggles,which are made of pieces of wood with two narrow slits for the eyes, each about large enough for a half-dollar to be slipped through it, are satisfactory in that they do not cloud over and that they protect the eyes from snow-blind ness; but the difficulty with them is that the range of vision is so restricted that it is as if you were looking out through a pair of key holes in a door. This is especially troublesome on rough ice or uneven ground, where you keep stubbing your toe against every obstacle, for through the narrow slits you can see what is in front of your feet only by looking directly down.

As my chafed foot was not completely recovered yet, and as Dr. Anderson was snow-blind, it fell to Natkusiak and Tannaumirk to go for the meat of the caribou Dr. Anderson had shot. It was an other cold, clear day as it had been the day before, and it furnished us with yet another example of the fact that Eskimo do not have com passes in their heads, for although the caribou had been killed and cached only about seven miles away from camp, Natkusiak was unable to find them in an all-day search and the two of them returned home after dark with an empty sled. This meant loss of valuable time, and worst of all, the consumption by us and our dogs of the few remaining pounds of dried meat we had brought with us from home. It is of course always wise to eat your green meat first and keep the light and condensed dried meat to the last.

The place where the two deer were cached was plainly visible with the glasses from our camp, so that it seemed likely that the next day Natkusiak and Tannaumirk would be able to find it, which it turned out that they did. We had delayed so long now, however, that two caribou were hardly sufficient meat to go on with, so that I went across the Horton River a mile or two east of where the Eskimo went to get the cached meat, and shot three caribou and a fine specimen of white wolf. This wolf was not only fat and excellent eating, but its skin was of great value, either scientifically or commercially;-scientifically because the animal is rare, and commercially because the Eskimo of the Mackenzie district and therefore the members of our own party value the skin highly as trimming for their winter coats. A wolfskin of the type which the Eskimo most admire can, when cut into strips, be sold for as much as twelve foxskins, which being translated into dollars at the prices quoted in 1912 would mean from one hundred to one hundred and twenty dollars for each wolfskin. Natkusiak and Tannaumirk heard my shooting when I bagged the three caribou, and after discovering the cached meat they came over and helped me skin, and took on their sled some of the meat. The next day we spent in hauling the rest of the meat to camp and in making a platform cache upon which to leave behind what we could not take with us. Besides meat, we left also in this cache the valuable wolfskin and the skins of two caribou which we intended for scientific specimens. We knew very well that this cache would not be safe from wolverines, but counted on the rarity of those animals in these parts for a chance to get back before everything had been destroyed. The wolves and foxes, we knew, would be unable to steal from a seven-foot high platform.

May 1, 1911

Vilhjalmur Stefansson

My Life with the Eskimo - Chapter 17

Besides that, this is the season which the Eskimo give up to the accumulation of blubber for the coming year. Fresh oil is not nearly so palatable or digestible as oil that has been allowed to ferment in a sealskin bag through the summer. A single family's store of oil for the fall will run from nine hundred to two thousand pounds.

Just northeast of the east end of Lambert Islandwe found, as we had expected, the village of the Noahanirgmiut Eskimo, con sisting chiefly of old friends and hunting companions of ours from the Bear Lake hunt of the summer before, but there were with them also a few families we had not seen. The Eskimo visit about a great deal, and although it is always possible for any one to say, “ This is the village of such and such a people,” still you are almost sure to find in any village members of one or more other tribes and generally of several. These visits are sometimes temporary, but commonly a family leaves its own tribe and joins another to be with it a period of a year, returning home at the end of that time, although sometimes the visit is only for a summer. A man who is in need of a new sled or a new bow, but whose own tribe hunts in a woodless country, may, for instance, join for the summer hunt a group that intends to go south to Bear Lake, in order to supply himself with the wood he needs. The Noahanirgmiut were still living on seal meat and were making no attempt to kill any of the numerous caribou that were continually migrating past. I thought at first that there might be some taboo preventing them from hunting caribou on the ice, but this they told me was not so. It was simply that they had never hunted caribou on the ice and had not considered it possible. It would in fact be a fairly hopeless thing for them to try it; and while no doubt some of them might occasionally secure an animal, they would waste so much time that the number of pounds of meat they obtained in a week's hunt in that way would be but a small fraction of the amount of seal meat they might have secured in the same time. Besides that, this is the season which the Eskimo give up to the accumulation of blubber for the coming year. Fresh oil is not nearly so palatable or digestible as oil that has been allowed to ferment in a sealskin bag through the summer, and besides that it is difficult often to get seals in the fall . By getting seals in the spring, therefore, they secure an agreeable article of diet for the coming autumn and provide themselves as well with a sort of insurance against hard luck in the fall hunt. Each family will in the spring be able to lay away from three to seven bags of oil. Such a bag consists of the whole skin of the common seal. The animal has been skinned through the mouth in such a way that the few necessary openings in the skin can be easily sewed up or tied up with a thong. This makes a bag which will hold about three hundred pounds of blubber, so that a single family's store of oil for the fall will run from nine hundred to two thousand pounds.

To completely test the matter of whether there was a taboo or not, as well as to provide ourselves with fresh meat and our friends with a feast, Natkusiak and I intercepted one of the bands out of which he shot one and I shot three, two of the three, by the way, being killed in one shot as the animals were running past at a dis tance of about three hundred yards. The Eskimo immediately went at the skinning energetically, and I photographed them while they were at it . The meat was then cut up and divided equitably among all the families and the cooking began at once.

May 16, 1911

Vilhjalmur Stefansson

My Life with the Eskimo - Chapter 18

The Sound people are evidently the most prosperous Eskimo we have seen; they are the most "travelled” and the best informed about their own country (Victoria Island) and its surroundings. Dietary habits surrounding bear, musk-ox, fish, seals, and even macu roots are discussed.

General [ Comment). The Sound people are evidently the most prosperous Eskimo we have seen; they are the most " travelled ” and the best informed about their own country (Victoria Island) and its surroundings. While they have been to the Bay of Mercy on north Banks Island and west beyond Nelson Head on south Banks Island they do not seem any of them to have been across the [ Dolphin and Union) straits to the Akuliakattak summer hunting grounds ( near Cape Bexley on the mainland) , or to the sea anywhere on south Victoria Island except among the Haneragmiut and Puiblir miut. Those who have been to a little west of Uminmuktok have come from the east to it as visitors of the Ahiagmiut in most cases ( Hanbury's Arctic Coast Huskies? ). Hitkoak, about the most travelled of any, has been at the Bay of Mercy, well west of Nelson Head, to Uminmuktok and into Bathurst Inlet, and to the Arkilinik ( near Chesterfield Inlet]. He looks not over thirty -five. He says he has ceased travelling, for he has seen “ many places and none are so good as the [ Prince Albert] Sound country.” He told us that he and some other families with him killed not a single seal last winter - lived on polar bears alone. They got seal oil to burn from others in trade for bear fat and meat. Honesty seems on a higher level among them than among any other people we have seen except the Akuliakattagmiut and Haneragmiut. Their clothes are far the best, their tents the largest. They use far more copper than any other people — doubtless because it is more abundant [in their country ).

The Kogluktogmiut [of the Coppermine River] are very eager for metal rods for the middle piece of the seal spear. They never make any of copper, no doubt because copper is too scarce. Their ice picks are small : their seal hole feelers are all of horn or iron. In the Sound ( on the other hand] the copper ice picks are in some cases three quarters by one and a quarter inch and fifteen inches long. Most seal spears have middle pieces of copper the rest have iron (from McClure's ship? ). The seal hole feelers are most [ of them ) of copper. Some of their tent sticks are of local driftwood, some are round young spruce which they get from the Puiblirmiut who get them from our neighbors of last August. Some sleds come from Dease River; some from Cape Bexley, but in either case they have been bought of the Puiplirgmiut or the Haneragmiut. Their stone pots are said to be all from the Utkusiksialik or Kogluktualuk ( Tree River). Some they got from the Puiplirgmiut by the road Natkusiak and I came last week, some around the point [ Cape Baring) from the Hanerag miut by the road we are taking now. Their fire stones [iron pyrite for striking fire) are some from the Haneragmiut, some picked up in the mountains north of the Sound. The copper is all from the mountains northeast of the bottom of the Sound. They say some [detached ] pieces of pure copper (in those mountains) are as high as a man's shoulder and as wide as high; others project out of the hill side and are of unknown size. East of Prince Albert Sound (on the Kagloryuak River) they use willows chiefly for fuel in summer these are four to five feet high in places. Heather [for fuel] is also abundant. The musk oxen are confined to the unpeopled sections of north and northeast Victoria Island and to Banks Island. They think there are a few deer in north Victoria Island in winter but none in south Victoria Island. The charms that starved the Banks Island people ( see above] deprived that country (sea and land both ) of food animals for a time, but these have gradually increased and are Banks Island has again become a good country. Nevertheless people never hunt there summers. There is plenty driftwood along the south shore of Prince Albert Sound, some along the north shore. There is plenty (drift ]wood northwest of Nelson Head [ Banks Island) and considerably east of it, but it is hard to find in winter. There are plenty of macu roots (polygonum bistontum) on the Peninsula between the Sound and Minto (Inlet] — and elsewhere. People eat plenty of them. Many good fishing places here and there, but they do not live to nearly such an extent on fish as do the Ekalluktogmiut, who eat fish all winter, as well as seal.

These macu roots form on the mainland the chief food of the marmot and the grizzly bear, both of which are absent from Victoria Island. All Eskimo known to me use this root as food —the Alaskans extensively , but the Victorians to a negligible extent only.