Recent History

October 5, 1949

Helge Ingstad

Nunamuit: Among Alaska's Inland Eskimos

The Nunamiuts thrive on this almost exclusively meat diet; scurvy or other diseases due to shortages of vitamins do not exist. They are, in fact, thoroughly healthy and full of vitality. They live to be quite old. I lived only on meat for nearly five years.

I am writing at the beginning of October. Now the women are going for trips up the hillsides in small parties and enjoying themselves picking berries and gossiping. They find a fair number of cranberries and whortleberries, but no great quantities. Cloudberries are scarce in the Anaktuvak Pass; there are said to be more farther north, on the tundra.

The berries are stored raw, sometimes in a washed-out caribou's stomach, and mixed with melted fat or lard. This dish is called asiun and is considered a special delicacy.

They also dig up some roots. The most sought after are maso, qunguliq (mountain sorrel), and airaq. What is collected is consumed before winter sets in. No new green food is to be had till May; then roots and the fresh shoots and inner bark of the willow are eaten. Thus, for about seven months the Nunamiuts live on an exclusively meat diet, and for the rest of the year their vegetable nourishment is very scanty.

The caribou is dealt with traditionally. Every single part of the animal is eaten except the bones and hooves. The coarse meat, which in civilization is used for joints and steaks, is the least popular. In autumn and spring it is used to a certain extent for dried meat; otherwise it is given to the dogs. The heart, liver, kidneys, stomach and its contents, small intestines with contents (if they are fat), the fat round the bowels, marrow fat from the back, the meat which is near the legs, etc., are eatn. Both adults and children are very fond of the large white tendons on the caribou's legbones; they maintain that food of this kind gives one good digestion. The head is regarded as a special delicacy; the meat, the fat behind the eyes, nerves, muzzle, palate, etc., are eaten. Finally, there are the spring delicacies--the soft, newly grown horns and the large yellowish-white grubs on the inside of the hide(those of the gadfly) and in the nostrils. The grubs are eaten alive.

The meat is often cooked, but to a large extent it is also eaten raw. The children often sit on a freshly killed caribou, cut off pieces of meat, and make a good meal. It is also common practice to serve a dish of large bones to which the innermost raw meat adheres. Dried meat and fat are always eaten raw.

The Nunamiuts' cuisine also offers several choice delicacies. First and foremost is akutaq. To prepare this dish, fat and marrow are melted in a cooking-pot, which must not get t oo warm, meat cut fine is dropped in on the top, and then the woman uses her fist and arm as a ladle to stir it about. The result is strong and tastes very good. Akutuq has since ancient times been used on journeys as an easily made and nourishing food and is fairly often mentioned in the old legends.

Then there is qaqisalik, caribou's brains stirred up with melted fat. A favourite dish is nirupkaq, a caribou's stomach with its contents which is left in the animal for a night and then has melted fat added to it. It has a sweetish taste which reminds one of apples. Finally, there is knuckle fat. The knuckles are crushed with a stone hammer to which a willow handle has been lashed. Then the mass is boiled til the fat flies up. The Eskimos attach great importance to the boiling's not being too hard; delicate taste. Sometimes it is mixed with blood, and then becomes a special dish called urjutilik.

The Nunamiuts like chewing boiled resin and a kind of white clay which is found in certain rivers. Salt is hardly used at all. If an Eskimo family has acquired a little, it is used very occasionally, with roast meat. The small amount of sugar, flour, etc., which is flown in in autumn is of little significance and has, generally speaking, disappeared before the winter comes. Some Eskimos do not like sugar.

For a while coffee or tea is drunk, but these are quickly finished. Then the Eskimos fall back on their old drink, the gravy of the cooked meat.

The Nunamiuts thrive on this almost exclusively meat diet; scurvy or other diseases due to shortages of vitamins do not exist. They are, in fact, thoroughly healthy and full of vitality, so long as sicknesses are not imported by aircraft. They live to be quite old, and it is remarkable how young and active men and women remain at a considerable age. Hunters of fifty have hardly a trace of grey hair, and no one is bald. All have shining white teeth with not a single cavity. The mothers nurse their children for two or three years.

It is an interesting question whether cancer occurs among the Nunamiuts or among primitive peoples at all. On this point I dare not as a layman express an opinion, but I heard little of stomach troubles. During my stay among the Apache Indians in Arizona (1936) a doctor in the reservation told me that cancer had not been observed among the people. According to a Danish doctor, Dr. Aage Gilberg (Eskimo Doctor, George Allen and Unwin, London, 1948), cancer is never sene among the Thule Eskimos in northwestern Greenland. The matter deserves more detailed investigation; it may possibbly give certain results of assistance to cancer research.

The Indian caribou hunters I once lived with in Arctic Canada had a similar meat diet and good health. As for myself, my fare was the same as the Indians' and the Eskimos'--practically speaking, I lived only on meat for nearly five years. I felt well and in good spirits, provided I got enough fat. My digestion was good and my teeth in an excellent state. After my stay with the Nunamiuts I had not a single hole in my teeth and no tartar.

No doubt the hunters of the Ice Age, in Norway and elsewhere, lived in a similar way many thousand years ago. We are probably in the presence of what is most ancient among the traditions of primitive peoples. Taught by experience, they have arrived at a manner of living which, despite its onesideness, fully satisifies the body's requirements. The principle is to transfer almost everything that is found in the caribou to the human organism.

It is interesting to note that the stomach and liver of animals are regular features in the diet of primitive peoples, whereas modern science has only quite recently established that these contain elements of special value to human beings. The remedy for the previously deadly pernicious anemia is obtained from them. The contents of the caribou's stomach and the newly grown horns merit a closer examination by modern methods. It is a question, for example, whether the cellulose of the moss decomposed in the caribou's stomach and thereby becomes available to the human organism. With regard to the horns, it is of interest that certain deer's horns from northeastern Manchuria have from time immemorial been a regular article of commerce in China, where they have been used as a cure for impaired virility.

Typed up by Travis Statham from physical book. This is the best quote in the entire book.

Note: Helge Ingstad lived to be 101 (1899-2001).

January 2, 1957

Vilhjalmur Stefansson

Rare Footage of Vihljalmur Stefansson the Arctic Explorer.

Vilhjalmur Stefansson appears on a television interview to talk about his balanced all meat diet of protein and fat.

Question: "Let's get to the fod. You must have longed for a green vegetable once"

VS: "I had to become a guest of the Eskimos and for four and a half months, I lived on literally nothing but fish and water, well, we had some blubber, some polar bear blubber, but apart from that, and at the end of four and a half months I was healthier than I ever been before. I'm enjoying every meal and feeling fine.

And this is on an exclusive meat diet?

Exclusive fish in this case. I have since then spent more than six aggregated years on red meat. That is seal meat, caribou meat, musk-ox meat, polar bear, grizzly bear and so on. You have to have fat with the lean, as lean and fat together make a perfect and balanced diet. You have everything you need if you have lean and fat. You don't need to eat organs. That's a curious folklore. People don't eat the organs except in emergencies.

January 1, 1969

Notes from the Century Before: A Journal from British Columbia by Edward Hoagland

Edward Hoagland writes the obvious point that "fresh meat will help combat scurvy."

"Steele's grandfather, having shipped around Cape Horn from Ontario in the 1890's, was prospecting with seven other men on Scurvy Creek, as it was named afterwards, which feeds into the Hyland. They'd been eating salt pork for months (even fresh meat will help combat scurvy), and they were all down and dying of the disease when some Indiians happened by and brewed up a pot of juniper tea. Five of the party refused to drink, saying it was Inidian medicine, but Grandfather Hyland and two of his friends drank it and lived. On their stubmilng, hallucinatory trip out, he picked up a chunk of gold ore which prospectors have been searching the river to match ever since." page 93 Hardcover

Eddontanajon: The Hylands and Frank Pete

I actually found this book in the Canadian History section of the Strand bookstore in Manhattan New York City and decided to buy it after finding it mentioning using fresh meat to cure scurvy. I can't even find an index so I think I stumbled upon it while browsing through a couple of pages. Lucky find!

June 1, 1975

Fred Bruemmer

Arctic Memories - The Northernmost People - Arctic Meat

When I first went to stay with Inuit, for weeks and often for months, I had misgivings about living on meat alone. It was not what my culture considered a "balanced diet." Yet common sense told me that since the Inuit were healthy I, too, would be healthy if I ate the meat in their fashion, some cooked, some raw. This turned out to be true, and hunger quickly took care of my ingrained cultural aversion to eating raw meat.

Page 44:

ARCTIC MEAT

When I first went to stay with Inuit, for weeks and often for months, I had misgivings about living on meat alone. It was not what my culture considered a "balanced diet." Yet common sense told me that since the Inuit were healthy I, too, would be healthy if I ate the meat in their fashion, some cooked, some raw. This turned out to be true, and hunger quickly took care of my ingrained cultural aversion to eating raw meat.

Explorers died in droves of scurvy in regions where Inuit had prospered for thousands of years. The reason was diet: the Europeans lived on salt beef, and its lack of vitamins eventually killed them. The Inuit thrived on fresh meat. Many of their favorite animal parts are rich in vitamins: liver contains high amounts of vitamins A and D (polar-bear liver is so rich in vitamin A it is poisonous; if one eats it, one can die of hypervitaminosis); muktuk, the skin of whales, is very rich in vitamin C, richer per unit of weight than oranges.

But meat, raw or boiled, is bland. The Inuit found salt disgusting; their words for salt and bitter sea water are synonymous. So, to add Tip to their diet, they fermented meat, a habit that horrified southerners, who reported with disgust that Inuit ate "rotten" meat. Actually the relationship between rotten meat and fermented meat is roughly that between spoiled milk and cheese. And properly ripened meat tastes very much like cheese. A favorite after-dinner delicacy of the Bathurst Inlet people with whom I lived was ingaluawinik, caribou mesentery fat, pressed into a pouch and fermented for months until it tasted like Danish blue cheese - only more so.

The Inuit of Little Diomede Island in Bering Strait keep most of their food in meat holes - spacious, stone-lined caverns, some of great age, dug deep into the frozen mountainside. Their diet when I first lived with them in 1975 was still largely traditional, and the people were healthy. The main food was boiled seal or walrus meat. Blubber, aged until it was saffron-yellow and then marinated in seal oil, was eaten as a zesty condiment with the bland meat, or with kauk, boiled walrus skin, which is best after it has aged in a meat hole for about a year.

The real masters in the art of fermenting meat are the Polar Inuit. They use ancient stone caches in which the meat slowly ripens, and they are as finicky and concerned about these caches as the people of Roquefort are about the drafts and temperature in the ancient limestone caves in which their famous cheeses mature.

The result of this process is such delicacies as iterssorag, year-old narwhal tail, slowly fermented in a blubber-lined rock cache, the skin bright green, the blubber olive green, the meat black and greenishly marbled, with the taste of the different parts ranging roughly from Brie to Roquefort to old Stilton; and, best loved by all, kiviaq, unplucked dovekies placed into blubber-lined sealskin bags and aged under rocks, untouched by direct sunlight, for about a year, until they have the pungent smell and flavor of old Gorgonzola.

In fall, I moved from Inerssussat up Inglefield Bay to the ancient narwhal hunting camp at Kangerdlugssuaq to live with a famous hunter; Ululik Duneq, and his family. As a gift, I took along from Qaanaaq a big chunk of very potent cheese. "Ah!" exclaimed Ululik as he tasted the cheese, "just like kiviaq!"

February 1, 2007

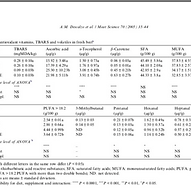

Antioxidant status and odour profile in fresh beef from pasture or grain-fed cattle

Measurements in grain and grass finished beef are 25.30 μg/g and 15.92 μg/g ascorbic acid

Abstract

The main goal of the present work was to determine the overall antioxidant status in fresh meat from animals fed different diets and to differentiate them through their odour profiles. Attributes were evaluated in beef from pasture or grain-fed animals with (PE and GE) or without supplementation (P and G) with vitamin E (500 UI/head/day).

Fresh meat produced on pasture (P and PE) had higher total ferric reducing antioxidant power (FRAP) levels than meat from grain fed-animals (G and GE) (P < 0.05). However, no differences were found on their ability to reduce ABTS+ (2,2′-azino-bis-(3-ethylbenz-thiazoline-6-sulfonic acid)), indicating that total antioxidant activity was preferentially due to the reduction potential than to the quenching capacity of tissue homogenates. Two-fold glutathione (GSH and GSSG are the reduced and oxidised forms, respectively) levels were found in the P + PE group respect to G + GE meat (P < 0.001). In addition, meat from pasture-fed animals presented a higher glutathione redox potential compared to grain-fed animals (−156.1 ± 6.1 and −158.1 ± 6.5 vs. −148.1 ± 13 and −149.8 ± 14.6 for P, PE G and GE, respectively), showing that the antioxidant status in fresh meat was affected by diet.

Enzymatic activity of catalase and glutathione peroxidase were equivalent for all dietary groups. Only superoxide dismutase activity was slightly higher (P < 0.05) in the P + PE group than in G + GE samples.

Odour profile analysis was performed in relationship to antioxidant parameters. Significant linear correlation coefficients (P < 0.05) were found for a set of sensors and the FRAP values. E-nose methodology successfully discriminated the odour characteristics of samples corresponding to pasture- or grain-based diet. Hence, it was possible to describe an analytical relationship between the odour profile and the antioxidant power of fresh meat.